CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 16.4

1. Antitrust laws make certain “anticompetitive” practices illegal because these practices raise prices and reduce output, which reduces the total amount of consumer surplus. Explain why antitrust action may not be helpful or necessary in markets that are:

Characterized by network goods

Highly contestable

Question 16.5

2. Explain the difference between competition “in the market” and competition “for the market.” What impact does each kind of competition have on prices and output in a market? Is one better than the other? How does the distinction make the application of antitrust laws more complicated?

Question 16.6

3. LinkedIn is an online professional networking site, much like Facebook or MySpace, except that it’s for connecting with classmates and colleagues to create networks that may be helpful in, among other things, finding job opportunities. The site boasts more than 300 million members (as of 2014) and claims to be the “world’s largest professional network on the Internet.” What made LinkedIn the largest professional network site? Since it is already the largest, does that mean LinkedIn will always be the largest? Why or why not?

Question 16.7

4. For each of the following pairs, determine which business is more likely to operate in a contestable market, and explain why.

The only clothing store in a small town vs. the only natural gas provider in a small town

The only clothing store in a small town vs. the only cable TV provider in a small town (What recent technologies make part b different from part a?)

De Beers diamond mining vs. H&R Block tax preparation services

Question 16.8

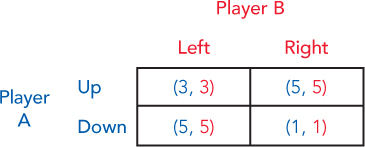

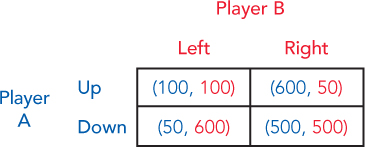

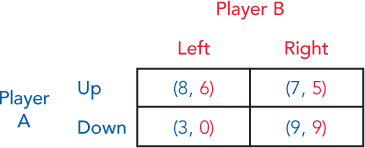

5. In the following three games, is each a coordination game or a prisoner’s dilemma? The best way to check is to see if there is exactly one Nash equilibrium; another way is to see if there is a dominant strategy for each player. To keep it a little challenging, we won’t give the actions obvious labels that might give away the answer. Higher numbers are always better:

Page 315

Page 315

Question 16.9

6. The mantra of Amazon.com CEO Jeff Bezos is “Get big fast.” As we saw in Chapter 13 on monopoly, one reason to “get big fast” is because in some industries the firm’s average cost will plummet as the firm expands—so size helps on the supply side. In this chapter, network effects illustrated how size helps on the demand side. With this in mind, explain the following real-world drives to get big fast: Do you think it’s mostly about increasing returns or mostly about network effects? Explain why:

Second Life, an online virtual world, lets people use many of its features for free. To use the best features, you have to pay.

Likewise, Match.com, the online dating site, lets people post profiles, look at other people’s profiles, and even get mail from other members for free. To send an e-mail to a member, you have to pay.

Adobe Acrobat Reader is free, but the software to create sophisticated Adobe documents is not.

King Gillette (real name) gave away his first disposable razor blades in 1885. They came free with the purchase of a box of Cuban cigars.

Amazon.com itself.

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 16.10

1. If you get a crack in your windshield, you can take your car to an auto glass repair shop where they will gladly try to repair your windshield, so you can avoid having to replace it. They guarantee their work, too; if the repair is not successful, they will allow you to apply the money you already paid for the unsuccessful repair toward the purchase of a new windshield. Sounds terrific, but how does this strategy relate to the material in the chapter? If all auto glass repair shops employ this strategy, what impact do you think this has on the price of a new windshield?

Question 16.11

2. Every so often, rumors float around Facebook claiming that the social networking site is going to begin charging its users a small monthly fee. So far, those rumors have always turned out to be false.

Do you use Facebook? If so, how much would you be willing to pay per month for access to Facebook? (If you don’t use Facebook—as unlikely as that is nowadays—how much do you imagine the typical user would be willing to pay to use it?)

Besides the price itself, what else would determine whether it was worth it to you to pay for Facebook? Is your response independent of others’ responses?

Do you think Facebook ever will charge users a fee? What are some reasons Facebook might do this? What are some arguments against this idea?

Question 16.12

3. Deciding which side of the road to drive on is a kind of coordination game. In some countries, people drive on the right side of the road, and in other countries (notably the United Kingdom and some of its former colonies), they drive on the left. These customs developed hundreds of years ago. If there were a single world standard, car companies could save some money by not having to produce both left and right types and cars would be a little bit cheaper. Why do you think it is that these customs persist? In other words, what keeps the world “locked in” to two separate kinds of cars?

Question 16.13

4. Consider the shipping container (the large box that stacks on cargo ships and attaches to trucks). If all containers are the same size and design, then the container can pass seamlessly between ships, trains, trucks, and cranes along the way. Today, the standard dimensions are 8 feet wide, 8.5 feet tall, and 40 feet long. (The recent book The Box tells the surprisingly gripping tale of how this size came to be the standard, and how it has cut the cost of shipping worldwide.) Let’s see how this standard dimension illustrates the meaning of “Nash equilibrium.”

Suppose an inventor created a new shipping container that was slightly cheaper to make, as well as stronger, but it had to be 41 feet long. Keeping the idea of standardization in mind, would this inventor be successful? Why or why not?

Page 316Suppose a container manufacturer reduced the strength of the end walls of his containers (saving him $100 per container made). Although this makes no difference to containers on a boat, containers on a train are at risk as the container bumps against the flatcar when the train hits the brakes. Who would tend to oppose these weaker, cheaper containers: the company whose products are stored in the container, the train companies who transport the goods, or both?

Why does Federal Express, the overnight delivery company, require everyone to use FedEx packaging for most shipments?

Question 16.14

5. It’s more efficient to go shopping when everyone else is shopping: This is one explanation for the rise of Christmas as a shopping season. Even many people who don’t celebrate Christmas do a lot of shopping and gift giving during this season. At the other extreme, a “dead mall” is one of the dreariest sights of modern consumer capitalism. Let’s see how a pleasant shopping experience is a network good.

Part of the pleasure of walking through a mall is the pleasure of seeing and being seen. When will you see more people at the mall: in the months before Christmas or at other times? So if you like seeing people, when will you tend to go to the mall? (This is an example of the “multiplier effects” so common in economics.)

When you were in high school (or perhaps middle school), you may have spent time hanging out at a mall. How was the mall like Facebook, MySpace, or other social networking Web sites?

Malls will spend more money on decorations and entertainment when they can spread this cost over a large number of consumers. Again, when will you expect to see more of these extra expenses: in the months before Christmas or at other times?

If Christmas is so great for malls, why don’t they have Christmas every month, spending money on decorations and singers all the time? Of course, they try to do this with Easter and back-to-school and Valentine’s Day, and so forth, but why do these attempts fail so miserably compared with the big success of Christmas? Answer in the language of network goods. (Hint: Once there’s a big chunk of the population committed to using Facebook, what’s the benefit to setting up another pseudo-Facebook?)

Question 16.15

6. Suppose a friend is taking an economics course at another college or university and his professor uses a different textbook. Your friend, after learning about monopolies and the lost gains from trade that result from monopolies, becomes very agitated about firms with market power, and he makes this statement: “It should be strictly forbidden for any company, in any market, to have more than 50% market share—market power like this always leads to higher prices, deadweight loss and inefficiency!” After you calm him down, how would you respond to this statement? Is your friend right?

CHALLENGES

Question 16.16

1. Why doesn’t everyone just switch to one language?

Question 16.17

2. Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman once asked, “Who would enter a demolition derby without the incentive of a prize?” (Source: Krugman, Paul. 1998. Soft microeconomics: The squishy case against you-know-who. Slate. www.slate.com/id/1933/. Posted April 24, 1998.)

The “demolition derby” he was talking about was the battle over Internet browsers: Many enter the battle, but only one (or two) survive. But let’s take his story literally: If there were two cars in a demolition derby, and each car costs $20,000 to build, and one car will be totally destroyed, how big will the prize probably have to be to get two people to enter if there’s a 50–50 chance of losing all your investment?

Page 317 Netscape?MINDY SCHAUER/ZUMAPRESS/NEWSCOM

Netscape?MINDY SCHAUER/ZUMAPRESS/NEWSCOMWhat if we want a really good demolition derby: one where 10 of these cars compete but only one survives. About how big will the prize have to be now?

Let’s draw the lesson for network goods: Since competition in network good markets is competition “for the market,” then it’s like winning a prize in a demolition derby. If there’s a fixed price of starting up a new social networking Web site (you need so many computers, so many nerds, so many advertisers), then when would you see a lot of firms competing for the prize: when the prize is large or when the prize is small? Thus, if we want a lot of competition for the market, do we necessarily want to restrict the profits of the winner?

Question 16.18

3. The market for college textbooks is an interesting one. One thing that makes it unique is that the person who chooses the textbook (the professor) is not the person who purchases the textbook (the student). Therefore, much of a textbook publishing company’s marketing is geared toward college professors. Most publishers of economics textbooks have developed (or have partnered with other companies to provide) online homework-management systems. The one that goes with this textbook is called EconPortal, as you may already know if your professor is using it. Explain how a homework-management system might benefit a professor. What impact might a homework-management system have on switching costs?

WORK IT OUT

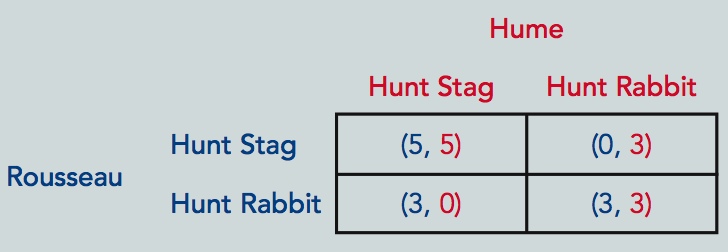

Prisoner’s dilemmas are common in real life, but not all real-life games are as dismal as the prisoner’s dilemma. One game, known as “stag hunt,” describes situations where cooperation is possible but fragile. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau described the game. He said that a lot of social situations are like going hunting with a friend: If you both agree to hunt for a large male deer (a stag), then you each have to hold your positions near each end of a valley so that the animal can’t escape. If you both hold to your positions, then you will almost surely get your kill. If one hunter wanders off to hunt the easier-to-find rabbit, however, then the stag will almost surely get away. Rabbit hunting works fine as a solo sport, but to catch a deer, you need a team effort. This is the usual way of writing the game:

If Rousseau is quite sure that Hume will hunt stag, will he also hunt stag?

If Rousseau is quite sure that Hume will hunt rabbit, will Rousseau still hunt stag?

There are two Nash equilibria here: What are they? (Check by looking in each box and asking, “Would one player unilaterally change his choice between rabbit and stag?” If so, this isn’t an equilibrium.)

Of these two equilibria, economists call one the “payoff-dominant equilibrium” and the other the “risk-dominant equilibrium.” You can figure out which is which by the process of elimination. What do you think is the biggest risk that might push someone to choose the “risk-dominant equilibrium”?

Is this a coordination game or is there a dominant strategy?

Page 318In the coordination games we looked at in previous questions, if you failed to coordinate, things turned out badly. Is that the case here?

Anytime someone says, “I’ll do it as long as I’m not the only one,” they’re probably describing a stag hunt. Wearing a cocktail dress to a dinner party, making a solid team effort, keeping your lawn mowed—all might be examples of stag hunts. In a stag hunt, if you think the other players are nice, then you’ll want to be nice yourself. But if you suspect they’re not nice, you’ll probably just be a “rugged individualist” and go hunt the rabbit on your own. With this in mind, think of two more examples of stag hunt situations on your own.

(For an excellent, somewhat technical treatment of how people might agree to hunt stag across many areas of life, see Skyrms, Brian. 2004. The Stag Hunt and the Evolution of Social Structure. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Skyrms is a philosopher who uses the tools of game theory to investigate important social questions.)