The Monopolistic Competition Model

Monopolistic competition takes the standard model of monopoly but allows for the free entry of competing business firms. To see how this works, let’s imagine the economic situation for the very first Chinese restaurant in our town of Fairfax, Virginia. In the short run, the first Chinese restaurant would use its market power to make profits, much like a monopoly. Unlike a monopoly, however, those profits would attract more entrants.

321

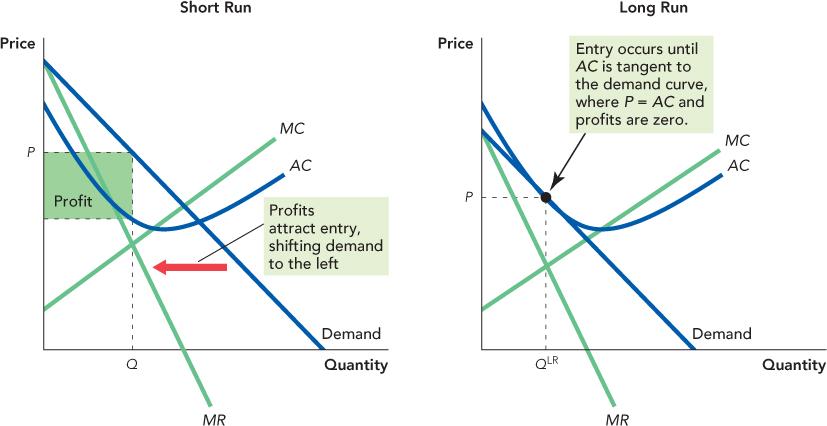

As more restaurants open, the demand curve facing the former monopolist shifts down and to the left, as some of the previous customers start patronizing other restaurants. In Figure 17.1 we show this process.

We begin on the left when the first Chinese restaurant in Fairfax has a monopoly. As you know, a monopoly maximizes profit by producing the quantity such that MR = MC. Profit is given by (P − AC) × Q and is shown by the green rectangle. All of this is exactly the same as for monopoly discussed in Chapter 13. The difference comes in the long run. No barriers to entry prevent an entrepreneur from starting a new Chinese restaurant in Fairfax so monopoly profits attract entry. Entry reduces the demand for the original restaurant. The firm continues to make profits so long as price is greater than average cost, P > AC, but that means entry occurs so long as P > AC. The end result is that the demand curve is driven to the left and down until it becomes tangent to (just touching) the average cost (AC) curve. At this point, P = AC and each firm in the industry is earning zero economic profits.

It’s the entry of competing business firms that drives the move from the left side of Figure 17.1 to the right side. Indeed, Yahoo lists 346 restaurants in or near Fairfax as serving some form of Chinese food.

Although producers under monopolistic competition don’t earn above-normal profits, they still are charging prices above marginal cost, P > MC, as you can see in the right panel of Figure 17.1. When P > MC, output is not at the efficient level. Remember that the price P measures the value to consumers of one additional meal, and the MC curve at QLR tells us the cost of producing one additional meal. Thus, when P > MC, the value of an additional meal exceeds the cost of an additional meal and social surplus would be higher if the firm produced more. Production under monopolistic competition, just as with monopoly, is not perfectly efficient.

322

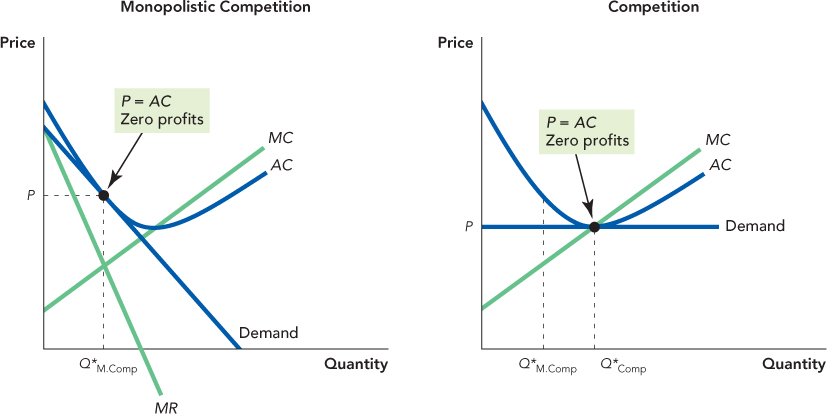

A monopolistic competitive firm is able to charge P > MC because its product is slightly different from the product of other firms. Your authors have a favorite Chinese restaurant in Fairfax—China Star. It’s where we take visitors to the university for lunch. The food there is spicier and the menu has some tasty dishes, such as scallion fried fish, that you can’t find elsewhere. Call us fussy if you like, but such features are specific examples of what is called product differentiation. Since there are no perfect substitutes for China Star, it can price its scallion fried fish above marginal cost and yet not lose us as customers. Product differentiation also means that under monopolistic competition, a firm does not produce at the minimum of its AC curve. To see this in a picture, Figure 17.2 compares long-run output under monopolistic competition (on the left) with that under competition (on the right).

Note that for comparison we show the monopolistic competition output level, Q*M.Comp and the competitive output level, Q*Comp in the right panel.

A competitive firm, sometimes also called a perfectly competitive firm, produces a product like oil that has perfect substitutes. As a result, the firm can’t control the price of its product, and just to earn zero profits, it must produce at the output level that minimizes average costs. A monopolistic competitive firm produces a slightly different product than its competitors, and so it can reduce output and raise the price without losing all of its customers. But when a monopolistic competitive firm reduces output, it no longer produces at the minimum of its average cost curve.

323

Is Monopolistic Competition Inefficient?

Although monopolistic competitive firms don’t produce at the minimum of their average cost curves, an offsetting advantage is the possibility of greater dynamism and product variety. If a restaurant comes up with a new recipe, for example, or some new and interesting décor, the demand curve for that restaurant’s product will shift up and to the right and that restaurant will enjoy higher profits. Or consider the market for books introduced at the beginning of the chapter. Books are priced at higher than marginal cost but there is a continual stream of authors who are trying to innovate and become the next Stephen King or J.K. Rowling. Although monopolistic competitive industries feature some market power, usually in the longer run, consumers are better off from the new products and the better matching of products to tastes.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 17.1

McDonald’s, Burger King, and Wendy’s are monopolistic competitors. What does this categorization tell you about each company’s long-term profits? Long-term costs?

McDonald’s, Burger King, and Wendy’s are monopolistic competitors. What does this categorization tell you about each company’s long-term profits? Long-term costs?

Question 17.2

Why do we classify McDonald’s and Burger King as monopolistic competitors rather than as pure competitors? Isn’t a hamburger just a hamburger?

Why do we classify McDonald’s and Burger King as monopolistic competitors rather than as pure competitors? Isn’t a hamburger just a hamburger?

We can see both the benefits and the costs of monopolistic competition in the market for drinking water. Water is simple: It’s uniform, and it’s often available for free. So who would imagine that you could sell water by the bottle for billions of dollars? And yet bottled water products like Dasani, Fiji, and Voss sell some $60 billion worth worldwide. The fact that there are many producers of bottled water means that the average costs of production is not minimized—bottled water would be cheaper if we could consolidate production in just a few firms, each of which would produce more. (And it would be even cheaper if we just used tap water.) On the other hand, many people do have a favorite brand of water so the product variety and experimentation of the industry does create value. Yes, sometimes we think this is a bit absurd—we have seen people buy bottled water at a restaurant instead of tap water even when the bottled water comes from exactly the same source! On the other hand, mineral water, sparkling water, and flavored waters, not to mention soft drinks, coffee, and tea (all mostly water), are different and it’s hard to say how different is different enough to justify the extra costs.

Keep in mind also that the market is a discovery process. Consumers may not even know that they want a product until entrepreneurs test the market and make new discoveries. Who knew that consumers would love milk shakes blended with coffee? Starbucks, however, has made millions selling “frappuccinos.”

As inefficiencies go, the fact that average cost is not minimized under monopolistic competition is typically considered fairly minor, but it is one way of understanding how monopolistic competition differs from competition.