The Economics of Advertising

The monopolistic competition model helps explain both the negative and the positive features of advertising. Perfectly competitive firms won’t advertise because at P = MC there is no gain from selling additional units of the product. But monopolies, oligopolies, and monopolistically competitive firms all wish to sell additional units and thus will attempt to use advertising to differentiate their products and build brand identity. These communications embody both information and persuasion.

Informative Advertising

Informative advertising is advertising about price, quality, and availability. Supermarkets, for example, send out newspaper supplements boasting of low prices for hamburger, apples, and milk. Price advertising is part of the competitive process, and there is good evidence for how advertising lowers prices and improves consumer welfare. In some states, for example, it used to be illegal for optometrists to advertise prices for eyeglasses; this restriction allowed economists to test the effect of advertising on prices. Would the states with advertising restrictions have lower prices for eyeglasses, on the theory that optometrists would save money if they didn’t advertise and would pass on these lower costs to consumers? Or would states with restrictions on advertising have higher prices, on the theory that without advertising there would be less competition? The states that allowed price advertising for eyeglasses had systematically lower eyeglass prices; in other words, advertising improves the competitive process. The same pattern—lower prices where advertising is allowed—has been true for prescription drugs, retail gasoline prices, eye exams, and legal services.1

Other times, advertising promotes messages of quality, thereby informing consumers and also giving suppliers a better incentive to meet quality standards. Once it was discovered that high-fiber cereals may help prevent cancer, and such advertising was allowed by law, companies had (1) a greater incentive to produce and advertise high-fiber cereals and (2) consumers became better informed about the benefits of high-fiber cereals and they ate more of the healthier cereals.2 These two processes were mutually reinforcing.

A lot of advertising is about telling people what’s out there. As of 2010, it was more common to see advertisements for the iPad in Berlin than in Virginia, or for that matter, Silicon Valley. Why? Germans are less familiar with Apple products in the first place. Advertising tells customers about new products, what they do, and why they are beneficial.

Advertising as Signaling

Sometimes advertising doesn’t appear to be about price, quality, or availability but the ad itself could be informative. If a new product debuts with a lot of accompanying advertising, consumers might infer that the seller expects the product to make a big splash, as with the iPad ads in Germany. The biggest piece of information is the ad itself. Apple was trying to get German consumers to think, either explicitly or implicitly, “If they’re spending so much advertising on this new product, they must expect it to have a long and profitable life. There really is something to this iPad after all.” That makes potential customers more interested in buying or at least sampling the product. Similarly, if a new movie or musical release is accompanied by a lot of ads, consumers will rationally infer that the producers expect the new product to hit it big; for a while, it seemed that Avatar commercials were everywhere. It might seem that the advertising creates the demand, but we also have to take into account that the firms who believe that their products are likely to be hits are the ones who have the biggest incentive to advertise.

Advertising as Part of the Product

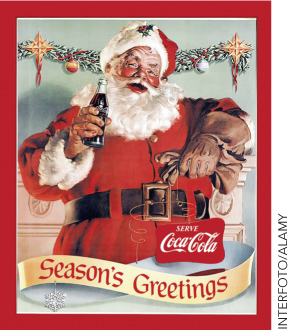

It’s obvious that a lot of advertising is simply about trying to change our minds and not about information at all. You can watch a Coca-Cola ad on YouTube that has no words, catchy music, lots of beautiful images including tumbling snowmen, no information about price, a cool dude pulling a Coke out of a vending machine, and at the end you see on the screen the simple words, “The Coke side of life.”3 Coke ads have been, well, vague for many years. Previous slogans include “The pause that refreshes,” “Thirst knows no season,” “Things go better with Coke,” and “The real thing.”4 It’s not so well-known that Coca-Cola publicized the idea, through its ads, of Santa as an old man in a red suit, but that shows how central Coke ads have been to our national consciousness.5 It’s not obvious how these messages have anything to do with informing buyers about Coca-Cola, if only because just about everyone already has heard of Coke. Worldwide, for all brands, Coca-Cola spends several billion dollars a year on advertising. Like Apple, Coca-Cola is trying to nudge the market in the direction of monopoly, and away from a state of affairs where consumers view different soft drinks as close substitutes.6

Yet, is persuasion through advertising always such a bad thing? Persuasion can give us tastes that appear silly or unjustified to outside observers, such as when we believe that drinking a particular beer will make us more suave or more attractive to potential dates. Nonetheless, persuasion also can deepen our enjoyments and our memories.

Here’s an example of how advertising gives us richer memories. In a blind taste test performed by researchers, the subjects reported roughly equal preferences for Coke and Pepsi. As part of the same test, the subjects were given one cup labeled as “Coke” and another cup, also containing Coke, but unlabeled. The subjects reported greater enjoyment from drinking the labeled cup and brain scans showed that they were activating the memory regions of their brain when they offered these reports. The researchers suspected that the subjects were associating Coke with fond images from ads or from earlier moments in their lives. It was not possible to replicate the same effect of “enhanced enjoyment from memory” when labeled and unlabeled Pepsi were put in the cups and sampled by subjects. In other words, the very act of thinking about the Coke brand has resonance with a lot of customers.7

It’s possible to read this story in two differing ways. Are the people who enjoy the Coke being “manipulated” or “tricked” by the advertisers? (If so, do your friends ever manipulate or trick you in the same way? Do you ever manipulate or trick them?) Or do the Coke ads mean many of us enjoy the Coca-Cola product more? Do the ads themselves enhance consumer welfare by turning a sweet, fizzy drink into something more? It’s common that people bring their value judgments to bear on advertising, as some will condemn and others will praise persuasive ads; economic science itself does not give us a means of deciding which ads are good and which are bad, all things considered. What we do know is that persuasive advertising can create some market power by brand differentiation, but at the same time advertising also helps people enjoy a lot of products.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 17.3

Wood is used to build houses. All houses have windows. Why do we see advertisements for different window makers but not for different producers of wood?

Wood is used to build houses. All houses have windows. Why do we see advertisements for different window makers but not for different producers of wood?

Question 17.4

Which category of advertising described in this chapter best explains a product endorsed by a famous athlete? Why? What if the product has nothing to do with sports, such as antifreeze or autos?

Which category of advertising described in this chapter best explains a product endorsed by a famous athlete? Why? What if the product has nothing to do with sports, such as antifreeze or autos?

Advertising, whether informative or persuasive, also helps finance many useful goods and services. Why is Google available on the Web for free? Because the company earns income by selling click-through ads and thus doesn’t need to charge users of a Web search. In fact, Google has an incentive to provide search services for free in order to maximize the number of people who will see the ads that it sells. Advertisements make newspapers and cable TV much cheaper than otherwise would be the case; for instance, a typical newspaper earns more from its ads than from its subscription revenue. In this sense, you, as a reader, benefit from ads even if you don’t care about the advertised products. There was even a high-school calculus teacher in San Diego, who, when the school budget was cut, responded by selling ads on his classroom exams. The going rate was $10 for a quiz, $20 for a chapter test, $30 for a semester final.8 Not everyone enjoys every ad, but advertising is an important part of what makes business work—at the most fundamental level, advertising is about bringing businesses and customers together.