Common Resources and the Tragedy of the Commons

Common resources are goods that are nonexcludable but rival.

Common resources are goods that are nonexcludable but rival. An example is tuna in the ocean. Until they are caught, the tuna are unowned—hence nonexcludable—and it’s difficult to prevent anyone from fishing for tuna. But tuna are not public goods since when one person catches and consumes a tuna, that leaves fewer tuna for other people. The result of nonexcludability and rivalry is often the tragedy of the commons, overexploitation and undermaintenance of the common resource. As a result of the tragedy of the commons, tuna are being driven toward extinction.

The tragedy of the commons is the tendency of any resource that is unowned and hence nonexcludable to be overused and undermaintained.

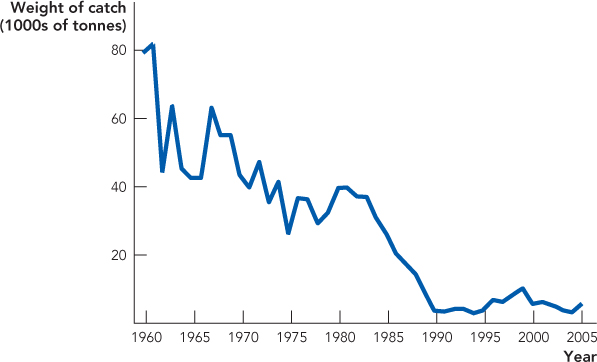

Since 1960, the tuna catch has decreased by 75% (see Figure 19.1). The southern bluefin is highly prized as sushi and demand has increased as sushi has become more trendy. The increase in demand and the decrease in the catch have driven up prices so a single choice tuna can now fetch $50,000 or more at the Tokyo fish market. As a result of the high price, corporations hunt tuna across the oceans in fast ships using satellites, sophisticated radar, and onboard helicopters. The sad truth is that so many fish are caught, various types of sushi may soon become a thing of the past.

Source: Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna.

359

Tuna aren’t the only fish headed toward extinction. A 2006 paper in Science estimated that if the long-term trend continues, all of the world’s major seafood stocks will collapse by 2048. Already nearly 30% of seafood species have collapsed (defined as a decline in the catch of 90%). As seafood species decline so do all the species that depend on them in the food chain. Overfishing is draining the oceans of fish.

Overfishing, however, is not primarily caused by increased demand. People like to eat chickens even more than they like to eat tuna but chickens are not going extinct. Why not? The difference is that chickens are owned and tuna, “chickens of the sea,” are unowned.

To see why ownership means that tuna are scarce and chickens are plentiful, let’s take a closer look at the incentives of fishermen and chicken ranchers.

Everyone, including the fishermen whose livelihoods depend on tuna, knows that tuna are being fished to extinction. So, you might think that the logical thing for a tuna fisherman to do is to fish less. But that’s not correct. If Haru, a Japanese tuna fisherman, fishes less, will there be more tuna for him to catch in the future? No; if Haru fishes less, that just leaves more tuna for other fishermen to catch—fishing less doesn’t help Haru because he doesn’t own the tuna until it’s in the hold of his ship. Since Haru doesn’t own the tuna in the ocean, he has no way of securing the fruits of his restraint.

Compare the incentives facing Haru with those facing Frank Perdue, the legendary chicken entrepreneur. Will Frank Perdue ever let his chickens go extinct? Of course not. Perdue makes money from his chickens, so to maximize profits, he will keep his stock of chickens healthy and growing. If Perdue “over-fishes” his chickens, he pays the price. If Perdue exercises restraint and grows his flock, he gets the benefit. In short, Frank Perdue will never kill the chicken that lays his golden eggs.

The problem of overfishing is one example of the tragedy of the commons, the tendency for any resource that is unowned to be overused and undermaintained. The theory goes back at least to Aristotle who in criticizing Plato’s idea of raising children in common said, “that which is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it.”1

Do you live with other students? Take a look at your kitchen—that’s the tragedy of the commons. Other examples of the tragedy of the commons include the slaughter of the open-range buffalo during the nineteenth century, deforestation in the African Sahel region, and the hunting of elephants to near extinction.

The tragedy of the commons applies especially strongly to resources like fish, forests, and agricultural land because these resources must be carefully maintained to remain useful. But when resources are unowned, the users do not have strong incentives to invest in maintenance because maintenance mostly creates an external benefit, not a private benefit. In other words, the fisherman who throws the small fish back mostly increases other people’s future catch, not his own. The tragedy of the commons is thus a type of externality problem like those we examined in Chapter 10.

360

We typically call something a tragedy of the commons when the lack of maintenance is so severe that exploitation is pushed beyond the point where the resource reproduces itself. To maintain a healthy stock of fish, for example, the yearly catch of fish must be no more than the yearly increase in fish population. If a population of 100 fish grows by 10% every year, then fishermen can catch 10 fish forever. But if the fishermen catch just one more fish, 11 fish per year, the stock of fish will be extinct in just 26 years. (See the appendix for a proof.) So, the fishermen who overfish are not just driving the fish into extinction, they are driving their own way of life into extinction—that’s a tragedy.

Happy Solutions to the Tragedy of the Commons

The tragedy of the commons can sometimes by averted in small groups. Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in economics, found that all over the world, small villages and tribes have avoided the tragedy of overfishing a lake or overgrazing a pasture through the enforcement of norms. A tribe member who takes too many fish from the common lake will be shunned, like someone who litters in a public park. A tribe member who exercises restraint and throws the small fish back will be respected. Tragedy of the commons problems, however, are more difficult to solve when a lot of unrelated people have access to the common good.

Command and control and, more recently, tradable allowances have been used to solve tragedy of the commons problems, just as they have been used to solve other externality problems, as discussed in Chapter 10. When fishing stocks have neared depletion, for example, governments have tried command and control solutions like limiting the number of fishing boats. To protect their salmon fishery, British Columbia limited the number of boats in 1968. Unfortunately, the scheme did not work well because the fishermen installed more powerful engines and better electronics for finding fish—this is often called “capital stuffing” because the fishermen stuffed their boats with expensive capital so those boats could be more effective. As a result of capital stuffing, the value of the typical fishing boat tripled in just 10 years; not surprisingly, the salmon fishery continued to decline. Similar problems have occurred when governments have restricted the number of days that fishing is allowed.

New Zealand pioneered an alternative approach in 1986 with individual transferable quotas (ITQs). ITQs are just like the pollution allowances that we looked at in Chapter 10; the owner of an ITQ has the right to catch a certain tonnage of fish. The sum of the individual ITQs adds up to the total allowable catch, which is set by the government.2 ITQs can be bought and sold and the government does not restrict the types of boats or equipment that the fishermen use so resources are not wasted by capital stuffing.

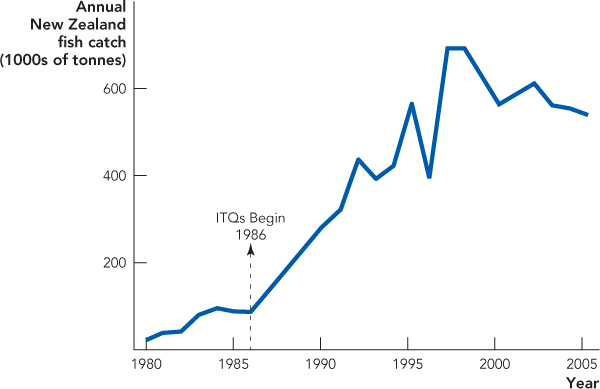

The ITQ system has been very successful. Figure 19.2 shows that after the ITQ system was put into place, the fish catch in New Zealand increased—in other words, preventing the fishermen from overfishing increased the amount of fish that they caught! This may seem paradoxical but it’s just a reminder of why the tragedy of the commons is a tragedy—when each fisherman chooses to fish rather than show restraint, the net result is less fish for everyone.*

361

Source: Fishery Statistics: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

How to Save a Dying Ocean

http://qrs.ly/mg4arcd

New Zealand was able to create an ITQ system and rescue its fishery because most of the New Zealand fish live and spawn within 200 miles of New Zealand’s shore—the economic zone that international law assigns exclusively to New Zealand. Thus, the New Zealand government was able to create property rights and exclude anyone who didn’t have the right to fish (i.e., an ITQ) from catching fish within its waters. Property rights in other common resources such as African elephants have also been created and have resulted in substantial improvements.

Unfortunately, it’s not easy to create property rights in all common resources. Southern bluefin tuna, for example, migrate throughout the Pacific, and some have been tagged and tracked across thousands of miles of ocean. So any solution to the tragedy of the tuna commons will require a multicountry agreement. That’s not impossible. In the 1970s, scientists discovered that certain chemicals commonly used in aerosols could disrupt the ozone layer, which protects the earth from UV-B radiation. Protecting the ozone layer is a public good since it is nonexcludable and nonrival. Fortunately, an international treaty called the Montreal Protocol has been signed by 195 of the 196 United Nations member states and it restricts the use of chemicals that damage the ozone layer. The treaty is widely regarded as the most successful environmental treaty as emissions of ozone-depleting chemicals have declined and the ozone layer has begun to recover.3

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 19.4

Why do small communities find it easier to deal with common resource problems than a state or a country?

Why do small communities find it easier to deal with common resource problems than a state or a country?

Question 19.5

Why is the establishment of property rights a key way to solve the problem of some common resources?

Why is the establishment of property rights a key way to solve the problem of some common resources?

Similarly, if there were world agreement, technology could be used to tag tuna and create property rights, but as we know from our discussion of the Coase theorem in Chapter 10, the more parties required to make an agreement, the greater the transactions costs and the less likely a solution. Moreover, rather than working to create property rights or restrict fishing to sustainable levels, most major governments today subsidize fishing extensively, which is making the tragedy of the commons worse. Thus, the tragedy of the tuna commons may not have a happy solution any time soon, either for sushi lovers or for tuna.

362