Meddlesome Preferences

Even if exploitation isn’t an issue, many people have a gut feeling that trading kidneys for money is just wrong. How much should this gut feeling count when thinking about justice?

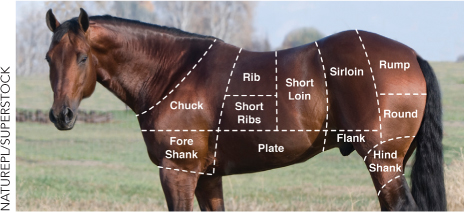

Consider this: is it okay to eat a horse? Not in California. Millions of Californians voted for a law that says, “No restaurant, cafe, or other public eating place may offer horsemeat for human consumption.” The market in horsemeat is open, however, in Europe and Japan where you’ll find horse on the menu at many restaurants. In Japan, it’s even common to find raw horsemeat for sale, as a kind of sushi. The National Horse Protection League doesn’t want anyone eating horses—especially foreigners—so it took out full-page ads in the New York Times to lobby for a ban on the export of horses to save them from a “brutal fate designed to feed foreign coffers.”

In America the horse is, so to speak, a sacred cow (unlike in India where the cow is a sacred cow). So should horsemeat be banned? And if horsemeat is banned because people don’t like the idea of someone eating horses, should kidney sales be banned because some people don’t like the idea of someone trading kidneys? And what about homosexuality, interracial dating, or various religious practices that do not meet with anything close to universal approval? Often these practices offend someone, so how much should these meddlesome preferences count?

397

Preferences about what other people do, even when those other people don’t interfere in any direct way with what you do, are sometimes called meddlesome preferences. It’s often difficult to resolve meddlesome preferences with other values that are considered important, such as liberty, rights, or religious freedom. We—Alex and Tyler—don’t usually put much normative weight on meddlesome preferences (we think that “live and let live” should be more popular), but that’s one of our value judgments, not anything intrinsic to being economists.