Lesson Two: Tie Pay to Performance to Reduce Risk

Consider an auto dealer who wants to motivate her sales staff. Let’s assume that all the auto dealer cares about is sales, so she is not worried that strong incentives will make her sales staff too pushy. Are strong incentives now the best? Maybe not.

414

Auto sales depend on more than hard work. Sales also depend on factors the staff has no control over, such as the price and quality of the car, the price of gas, and the state of the economy. If incentives tie earnings directly to sales, the sales staff are going to do great when the economy is booming but poorly when the economy is in a recession.

When sales vary for reasons having little to do with hard work, strong incentives may be more expensive than they are worth. Most people don’t like risk. Which would you prefer, $100 for sure or a gamble that pays $200 with probability  and $0 with probability

and $0 with probability  ? Gambling in Las Vegas can be fun but most people will prefer $100 for certain over a gamble with the same expected payoff. Similarly, suppose that there are two jobs: job 1 pays $100,000 a year for sure, job 2 pays $200,000 in a good year but $0 in a bad year. Suppose also that good and bad years are equally likely, so, on average, job 2 also pays $100,000 a year. Which job would you prefer? If the wages are the same on average, most people will prefer job 1, the less risky job. How high would the average wage have to be for you to prefer job 2? $110,000, $150,000, $175,000? The precise number is less important than the principle: The riskier payments are to workers, the more a firm must pay on average. Thus, if the sales staff has to bear the risk of a bad economy or a low-quality car, they will demand a big bonus for every sale. But if the sales staff demand a big bonus, what is left over for the owner? If the sales staff is sufficiently afraid to face these risks, the owner and the staff might not be able to agree on a mutually profitable strong incentive plan.*

? Gambling in Las Vegas can be fun but most people will prefer $100 for certain over a gamble with the same expected payoff. Similarly, suppose that there are two jobs: job 1 pays $100,000 a year for sure, job 2 pays $200,000 in a good year but $0 in a bad year. Suppose also that good and bad years are equally likely, so, on average, job 2 also pays $100,000 a year. Which job would you prefer? If the wages are the same on average, most people will prefer job 1, the less risky job. How high would the average wage have to be for you to prefer job 2? $110,000, $150,000, $175,000? The precise number is less important than the principle: The riskier payments are to workers, the more a firm must pay on average. Thus, if the sales staff has to bear the risk of a bad economy or a low-quality car, they will demand a big bonus for every sale. But if the sales staff demand a big bonus, what is left over for the owner? If the sales staff is sufficiently afraid to face these risks, the owner and the staff might not be able to agree on a mutually profitable strong incentive plan.*

Weak incentives insulate the sales staff from risk. If the owner is better able than the sales staff to bear the risk of a recession (perhaps because she is wealthier), weak incentives may be mutually profitable. In essence, the owner can sell the staff “recession insurance” by paying them with a fixed or nearly fixed salary. The sales staff “buy” the insurance by accepting smaller bonuses but, of course, their pay is more stable.

Bearing the risk of a recession might be worth it if hard work from the sales force is also the critical factor in sales. But if the state of the economy is a significant determinant of sales, then strong incentives have created risk with very little motivational advantage. Imagine if rewards were based solely on luck—what incentive would there be to exert effort? Similarly, if rewards are mostly based on luck, the incentive to exert effort will be low and many potential employees won’t want to face those risks at a price the owner is willing to pay.

Tournament Theory

When sales depend heavily on outside factors such as the state of the economy, tying bonuses directly to sales will reward or penalize agents for outcomes that are often beyond their

A tournament is a compensation scheme in which payment is based on relative performance.

415

If they are used cleverly, tournaments can tie rewards more closely to actions that an agent controls, thereby improving productivity and pay. To see how a tournament works in the business world, let’s start with sports, an area where we are all used to thinking about tournaments.

Imagine a golf game in which players are paid based on the total number of strokes to finish the course (by the nature of golf, fewer strokes mean better play and thus higher payments). If the weather is bad, scores will be high and agents won’t earn very much even if they work hard. If the weather is good (clear day, no wind), scores will be low and agents will earn a lot even if they don’t work very hard. Either way, when players are paid based on their absolute scores, random forces—such as the weather—will influence how much the players earn.

Now imagine that players are playing in a tournament with a fixed number of prizes, which of course is usually the case. The fixed number of prizes means that the players are competing against one another rather than against some external standard of achievement. Since every player plays with the same weather, the weather no longer influences rewards. Thus, a tournament limits the amount of risk from the external environment. A lot of sporting events, not just golf, are organized in the form of tournaments. Tournaments are also common in the business world.

For instance, paying sales agents based on relative sales will reduce environment risk, risk from external factors that are common to all the agents. When sales agents are paid based on relative sales, factors that the agents do not control such as the state of the economy, the quality of the product, and the price of competing products will no longer influence agent rewards. Here is the key: when factors that an agent doesn’t control no longer influence rewards, then factors that an agent does control—factors like effort—become more important determinants of rewards. Thus, pay for relative performance such as that used in a tournament can reduce risk and tie rewards more closely to actions that an agent controls. This will mean harder work, less risk, more output, and higher pay.

Improving Executive Compensation with Pay for Relative Performance

A good compensation scheme ties rewards to actions that an agent controls. How would you use the idea of pay for relative performance to tie executive pay more closely to actions that executives control?

Today, a large fraction of an executive’s pay is tied to the stock price of his or her firm. When the value of the firm rises, executives are often able to cash in stock options at profitable prices. But many factors other than executive effort or ability influence the price of a stock. When the economy does well, for example, the price of most stocks goes up. Similarly, when the price of oil goes up, the stock price of firms in the oil industry tends to go up—and surprisingly, so does the pay of executives in the oil industry, despite the fact that these executives have no control over the price of oil.8 Of course, when the price of oil falls, these executives are paid less, despite the fact that they may be working as hard as, or harder than, ever. The bottom line is that quite a bit of executive pay appears to be based on luck. But payment based on luck is not a good compensation scheme on either the upside or downside.

416

Is there a better way to pay executives? Instead of paying based on how well their stock performs, how about paying executives based on how well their stock performs relative to other firms in the same industry? If executives were paid based on relative performance, they wouldn’t reap big windfall profits when the industry boomed (due to no virtue of their own) but neither would they necessarily be paid less when the industry declined (due to no fault of their own).

Pay for relative performance seems to make a lot of sense but it has not been widely adopted. As a result, some observers suspect that the complicated stock option schemes currently used to reward executives are less about creating incentives than about creative accounting that takes advantage of shareholders who do not closely monitor how much the executives are being paid. Interestingly, firms that have at least one very large shareholder—and thus at least one shareholder with an incentive to monitor the firm closely—do appear to base more executive pay on relative performance.9

In recent times, the American economy has experienced another problem with compensating senior managers, especially in banking and finance: Sometimes the incentive is to take too many “long tail” risks, namely risks that rarely go bad, but when they do, they go very, very bad. Let’s say a bank manager encourages his staff to make risky mortgage loans that go bad only once every 30 years, but when they do, they endanger the very existence of the bank and perhaps even the banking system. Most of the time the risks pay off, the bank prospers, and the managers get a nice bonus. Sooner or later, however, the mortgages go bad and the bank ends up insolvent or in need of a government bailout. How much do the managers suffer? Usually, they don’t have to give back their old bonuses and often the worst thing that happens—if that—is they are fired. In 2008, two investment banks, Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, went bankrupt. This wasn’t good for their managers, but over the 2000–2008 period, they had already pulled out about $1.4 billion (Bear Stearns) and $1 billion (Lehman Brothers) in cash bonuses and equity sales.10 Thus, even though these managers took on huge risks, they still profited handsomely. Many of them found other jobs or retired on their previous bonuses, so the penalties to discourage excess risk-taking aren’t so strong. Prior to the financial crisis of 2007–2009, the U.S. financial system took too many risks of this nature. It remains to be seen whether better incentives can be designed to overcome this problem.

Environment Risk and Ability Risk

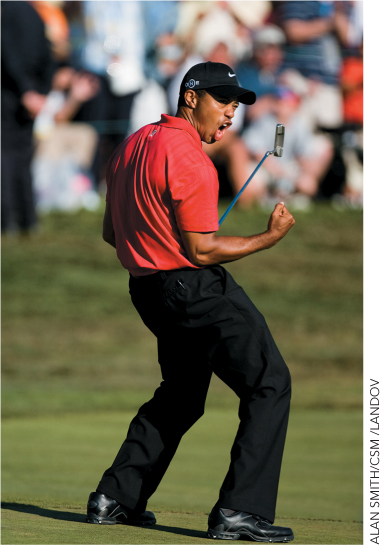

A tournament insulates rewards from environment risk due to outside factors that are common to all the players, but it adds another type of risk called ability risk. Imagine that you had to compete in a golf game against Tiger Woods. Would you put in more effort if you were paid based on the number of strokes or if you were paid based on who wins the game? The probability that you could beat Tiger Woods at golf is so low that if all you cared about was money, it would make sense to give up right away—why exert effort in a hopeless cause? Of course, for the same reason, Tiger Woods won’t need to try very hard either!

Remember, an ideal incentive scheme ties rewards to factors that an agent controls, such as effort. But winning at golf takes more than effort; it also takes ability. As far as an agent is concerned, someone else’s ability is just like the weather or the state of the economy; it’s not under his or her control. A golf tournament between players with highly unequal abilities doesn’t tie rewards to effort; it ties rewards to ability and that often causes people to shirk and slack. Thus, tournaments work best when the risk from the outside environment is more important than ability risk.

417

Tournaments can be structured to reduce ability risk. At a professional golf tournament, for example, players play in rounds with the weakest players being eliminated in early rounds, so when the final and most important round is played, the players have similar abilities. Similarly, tournaments are often split into age classes or experience classes (beginner, intermediate, expert) so that abilities are similar and each player has a strong incentive to work hard. In amateur but serious golf games, when players of different ability compete together, the high-ability players will often be handicapped, which makes competition more intense for all the players. A manager who wants a lot of effort will also structure tournaments so that rewards are closely tied to effort. A manager, for example, might create junior and senior sales positions with tournaments played within each class of employee.

Tournaments in business might seem a bit unusual but they are quite common. About one-third of U.S. corporations evaluate employees based on relative performance.11 Under the hard-nosed CEO Jeff Bezos, employees at Amazon must compete against one another for a limited number of promotions and employees ranked in the bottom 10% are often shown the door (a so-called rank-and-yank system). Even when employees are not explicitly rewarded based on relative performance, tournaments are often implicit. Lawyers, for example, compete to earn the prize of becoming a partner. Becoming the president of a corporation is a lot like winning a tournament. Imagine that a corporation has eight vice presidents and one president—the vice presidents compete to become the next president. The fact that moving up the corporate ladder is like competing in a tournament may also shed some light on the large salaries and perks of many corporate presidents. Personal chefs, corporate jets, and lavish parties might be a sign of the abuse of power but the perks of presidency may also motivate the eight vice presidents. In part, corporate presidents are paid a lot to motivate those beneath them.

Tournaments are wonderful at encouraging competition but sometimes competition can be too fierce. In a tournament, when one player falters, the others gain, so tournaments can discourage cooperation. One corporate vice president might be unwilling to mentor another if she sees a competitor waiting to take away her job. Thus, as usual, compensation schemes must be carefully designed to balance a variety of goals.

Tournaments and Grades

Let’s apply some of the insights from tournament theory to a competition that you are very familiar with: the competition for grades. Some professors grade on a curve, while others use an absolute scale. When a professor “grades on a curve,” there are a fixed number of “prizes”—A’s, B’s, C’s, for each class. The competition for grades becomes a tournament.

418

The costs and benefits of being graded on a curve are just like the more general analysis of tournaments. Grading on a curve reduces environment risk but increases ability risk. Can you think of some examples of environment risk? Suppose that your professor is hard to understand—perhaps the professor has an accent or teaches the material too quickly or is simply not a good teacher (unlike us!). Fortunately, if the professor grades on a curve, his or her bad performance doesn’t mean you have to fail. Bad teaching will reduce how much you learn but bad teaching harms everyone’s performance. If the professor grades on a curve, bad teaching need not reduce your grade or reduce your incentive to study.

A bad teacher who grades on an absolute scale, however, is double trouble. First, bad teaching means that you won’t learn much. Second, if the grading is on an absolute scale, not learning much means that even if you work hard, you will get a low grade. There isn’t much incentive to work hard in that case.

Grading on a curve, however, does have disadvantages—grading on a curve means that you will be competing directly with the other students in the class. If you happen to be in a class with a handful of super-brilliant students, it’s like golfing against Tiger Woods (unless you are the academic Tiger Woods). Even if you learn a lot and work hard, you won’t get a high grade and that reduces your incentive to study.

Grading on a curve, therefore, creates better incentives to study when the big risk is that the professor will be bad (an environment risk), but it reduces the incentive to study when students are of very different abilities (ability risk). Grading on an absolute scale creates better incentives to study when students are of very different abilities (ability risk), but reduces the incentive to study when the big risk is that professors will be bad (environment risk).

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 22.3

At one prominent university, a professor’s first name and middle initial are “Harvey C.” Undergraduates refer to him as “Harvey C-minus” because he is a notoriously hard grader. What are this professor’s incentives to be known as a hard grader? What type of students does he attract? Whom does he encourage to stay away? Why might this professor not want to grade on a curve?

At one prominent university, a professor’s first name and middle initial are “Harvey C.” Undergraduates refer to him as “Harvey C-minus” because he is a notoriously hard grader. What are this professor’s incentives to be known as a hard grader? What type of students does he attract? Whom does he encourage to stay away? Why might this professor not want to grade on a curve?

Question 22.4

How can a tournament create too much competition? Isn’t competition a good thing?

How can a tournament create too much competition? Isn’t competition a good thing?

What are some other effects of grading on a curve? Remember, tournaments tend to reduce cooperation. If your professor grades on a curve, other students might be less willing to help you with your homework (or you might be less willing to help them!). Study groups will probably be less common. Some students might even try to sabotage other students. Tournaments can also encourage the wrong kinds of cooperation. If a professor grades on a curve, in theory all the students could get together and agree not to study very much. This probably wouldn’t be a problem in a large class, but if two sales agents regularly compete for the “salesperson of the month” award, they could collude to reduce effort and rotate the prize between them.

Here’s another problem for you to think about. Suppose that the envi ronment risk is not bad professors but rather difficult material. Imagine, for example, that some classes are more difficult than other classes (quantum physics 101 vs. handball 101). If you really wanted to learn a little about quantum physics, but you were afraid of reducing your GPA, what type of grading system would you prefer? And to ask the classic economist’s question; under what conditions? See Thinking and Problem Solving question 6 for further discussion of this question.