Adverse Selection

Adverse selection occurs when an offer conveys negative information about the product being offered.

Groucho Marx, the famous comedian, once said that he didn’t want to belong to any club that would have him as a member. Believe it or not, the economist George Akerlof won a Nobel Prize for analyzing when Groucho-type reasoning makes sense and what the consequences are for market equilibrium and efficiency! Groucho was using the fact that a club was offering him membership to infer something about the quality of the club, namely that the club couldn’t be very exclusive. Akerlof analyzed the more general situation of adverse selection, when an offer conveys negative information about what is being offered.

Quick: Who is most likely to want health insurance? Answer: the sick. That’s adverse selection: The offer, in this case the offer to buy health insurance, conveys the negative information that the buyer is likely to have above-average health care costs. Notice that Groucho didn’t want to join a club that most wanted him as a member, and insurance companies don’t want to sell insurance to the people who most want to buy—this is the basic problem of adverse selection.

451

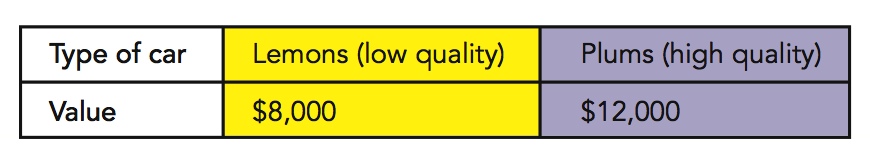

Let’s give another example that was first analyzed by Akerlof. Suppose that there are two types of used cars: lemons (used cars with a lot of problems) and plums (used cars in excellent mechanical shape). Lemons are worth $8,000; plums are worth $12,000. Suppose also that among the currently owned cars there are equal numbers of lemons and plums. Now, here is the key assumption of asymmetric information: Assume that only sellers know the true quality of their car and that there is no cheap way for buyers to distinguish lemons from plums.

The market structure is simple but the assumption of asymmetric information has surprising consequences.

Suppose that you were a buyer in this market. How much would you be willing to pay for a used car? You might reason that since there are equal numbers of lemons and plums, the probability is  that you will be purchasing a lemon and.

that you will be purchasing a lemon and.  that you will be purchasing a plum. Thus, you would be willing to pay the expected or average value, namely

that you will be purchasing a plum. Thus, you would be willing to pay the expected or average value, namely  .

.

This reasoning is incomplete. To see why, now put yourself in the shoes of a seller with a plum, a high-quality used car. Buyers are willing to pay only $10,000 for a used car, but your car is worth $12,000. Do you sell? No.

Now put yourself back in the shoes of the buyer and think like Groucho. Even if half of the existing cars are plums, does it make sense to assume that half of the cars for sale are plums? No. In fact, no owner of a plum will want to sell, so the mere fact that a car is offered for sale suggests that it’s a lemon. How much are you willing to pay for a used car now?

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 24.2

Go to eBay and search for Picassos. What do you infer about these Picassos?

Go to eBay and search for Picassos. What do you infer about these Picassos?

Since buyers know that every used car for sale is a lemon, the most they will be willing to pay for a used car is $8,000.

Notice what is wrong with this outcome. Even if lots of people would like to buy a plum at $12,000 and lots of people would like to sell a plum at $12,000, there is no market for plums. Plums—the high-quality used cars—don’t trade. That is a market failure.

We assumed that there were only two types of used cars, but the outcome gets even more disturbing when there are many qualities of used car from low to high. The general logic is that of the vicious circle, or “death spiral.” Buyers can’t easily tell the quality of a used car so they play the averages. An average price, however, means that the owners of higher-quality autos aren’t getting a good price for their cars. The owners of high-quality used cars drop out of the market, thereby reducing the average quality of the cars for sale and, in turn, reducing how much buyers are willing to pay. The process continues until only the worst lemons are for sale.

Of course, in the real world not every used car for sale is a lemon. The reality is that about 35 million used cars (and small trucks) were bought and sold last year in the United States, as compared to about 12 million new cars.6 It hardly seems that the used car market has shut down, nor are used vehicle sales in the United States overwhelmingly dominated by low-quality lemons.

452

Now that we understand the problem, let’s turn to some of the market institutions, laws, and regulations that have evolved to deal with adverse selection.

How does the used car market manage to work as well as it does?

First, potential buyers can have an experienced mechanic look over the car. Similarly, used cars are also often accompanied by what are called “CARFAX” reports, which detail the repair history of the car. Both of these techniques help to overcome information asymmetry and increase trade.

A credible promise is one that the promisor has an incentive to keep.

Second, millions of used cars today are certified, which means they are bought by a dealer, inspected, repaired and refurbished, and then sold with an extended warrantee. The warranty reduces consumer fears about getting a lemon. A warranty also makes the dealer’s promise to sell a plum credible because if a dealer sells a lemon, the dealer ends up paying. Warranties are best when they are never used! The firm selling the warranty is often the original manufacturer of the car. Mercedes, for example, warranties certified preowned Mercedes vehicles. Thus, Mercedes’ reputation for high-quality new cars is also on the line when they sell certified preowned cars. That also reassures consumers and communicates the message that the car is really a good one.

Similarly, notice that many used cars are bought and sold between friends and family. If your brother tells you that his car is a plum, you may be more likely to believe him—because he’s your brother and also because if the car isn’t a plum, you can punish him in ways that you could not punish a stranger! In essence, reputation outside the market for used cars helps to sell used cars.

Third, suppose that some sellers of used cars will sell even when the price is low. Perhaps some owners of used cars simply love that new car smell and want to replace their used car regardless. Other owners have leased their cars and want a new car every two years, or perhaps they simply need the cash. If some used car owners sell even if they have a plum, that action raises the expected value of used cars and makes buyers more willing to buy and (other) sellers more willing to sell. Thus, the presence of some sellers who sell regardless of price keeps the price high enough so that other owners of plums want to sell.

Adverse selection hasn’t shut down the market for used cars because market institutions have developed to reduce information asymmetry and its consequences. It’s not that everyone has a great experience buying a used car (or a new car, for that matter), but the used car market is an active and well functioning market that gives many people the chance to buy (or sell) personal transportation at a discounted price.7 Still, an understanding of the dangers of adverse selection helps us understand how to do a better job buying or selling used cars.

Adverse Selection in Health Insurance

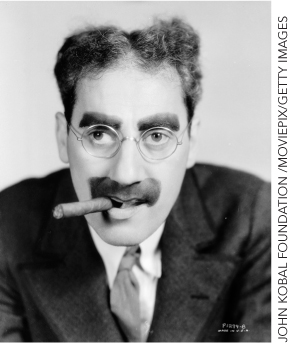

Let’s look in more detail at the challenge of selling health insurance. When a health insurance company offers a policy, it worries that perhaps the sickest individuals, or those with the greatest potential future problems, are the ones most likely to buy. After all, a perfectly healthy person doesn’t benefit much from the reimbursements offered by health insurance, unless, of course, some sudden accident befalls them. But if only the sick buy insurance, the insurance company has to raise its rates to reflect the higher costs. The higher rates in turn make health insurance an even worse deal for healthy individuals, pushing them out of the market. As rates rise and healthy individuals drop out of the market, the composition of customers becomes even more costly for the health insurance company, which in turn pushes rates yet higher. Figure 24.1 illustrates this process, which is sometimes called the “adverse selection death spiral,” with some specific numbers and assumptions.

453

454

As in the market for used cars, some market features help limit this adverse selection problem:

Inspections or Checkups An insurance company can inspect the health of potential insurance customers to overcome asymmetric information and adjust rates accordingly. If insurance companies can charge people different rates depending on their expected costs the adverse selection “death spiral” will be avoided.

Group Plans An insurance company can emphasize sales to groups, such as through the workplace, to increase the chances of signing up both healthy and unhealthy customers. In fact, most health insurance in the United States is not bought by individuals but by firms that purchase insurance for their employees as a group. Since healthier individuals typically cannot opt out of their employer’s group health insurance plan, this limits adverse selection problems. In addition, in the United States, as a matter of law, employer-supplied group health insurance plans have only a limited legal ability to kick out or raise rates for individuals who come down with financially costly health problems. That also helps to keep insurance markets working.

Conscientiousness The monetary value of health insurance is lower for healthier people so we assumed that healthier people will be the ones most likely to opt out of buying health insurance. There is some evidence for this but it’s not the full story. Some people simply value insurance more than others. In fact, it turns out that many of the people who take the best care of their health are also the people most concerned with making sure they are covered by health insurance. Consider Devin and Jan. Devin likes to drive fast and often forgets to wear a seatbelt. Jan keeps to the speed limit and makes sure everyone is buckled up before starting any trip. If you had to guess, who do you think is more likely to have health insurance, Devin or Jan? Devin needs it more than Jan and in a monetary sense the insurance would benefit Devin more than Jan, but we think Jan is simply the type of person who buys health insurance (and probably auto and home insurance as well). Insurance companies love people with temperaments like Jan’s because they buy insurance and they are careful about their health. If there are a lot of Jans in the world—that is, lots of people whose personality trait of conscientiousness correlates with demand to buy health insurance—then this will lead not to adverse selection but to positive selection (sometimes called “propitious selection”). Even if there are only some Jans, this will tend to counter and moderate the adverse selection death spiral.8

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed by President Obama and Congress in 2010, subsidizes the purchase of health insurance for poorer individuals and families. The so-called individual mandate, which compels many individuals to purchase health care insurance by force of law, is one of the most controversial aspects of the ACA. One motivation for the mandate is to avoid the adverse selection death spiral. The government fears that if the purchase of insurance is voluntary, then, even with the subsidies, many healthy individuals won’t buy insurance and that will push up costs and start the death spiral. The idea of the individual mandate is to push healthy individuals into health insurance pools, thereby lowering the cost of health insurance. Under this vision, if everyone is required to buy broadly similar insurance policies, there will be less adverse selection. It is no accident that some of the architects and designers of the law were economists who had studied the imperfections of health-care markets.

455

The critics of the Affordable Care Act, in contrast, focus on a moral hazard problem with insurance. When people are insured, they tend to behave differently—people with fire insurance may fail to install a sprinkler system that they would install if they didn’t have insurance, drivers with insurance may drive less diligently, banks that expect a government bailout if things go badly may take on more risk. In the case of health insurance, we aren’t so much worried about a person taking on more risk but of demanding more services. When patients, doctors, and hospitals know an insurance company is paying the final bill, the patients tend to demand more procedures and treatments. Doctors and hospitals, in turn, supply those procedures and treatments, knowing they will be paid for them, and that is a form of moral hazard at the expense of the insurance companies.

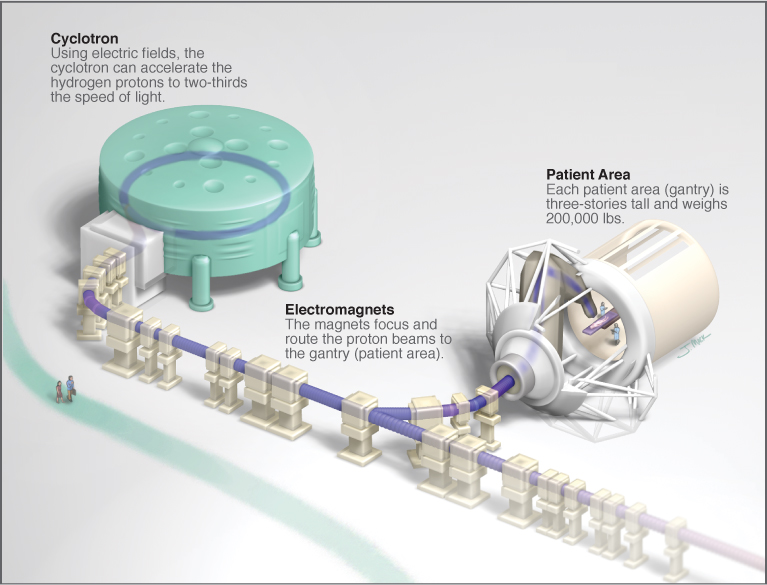

Hospitals around the country, for example, have been building nuclear particle accelerators—-which were once used only by physicists looking to understand the universe!—in order to treat cancer. The accelerators cost hundreds of millions of dollars and involve massive magnets and giant buildings. Unfortunately, there is very little evidence that so-called proton therapy improves health and even less that we need dozens of these facilities in the United States. If patients had to pay for these treatments out of pocket, they would be unlikely to want them but when insurance companies and taxpayers are the ones paying the bills, patients will demand them and hospitals will supply them.

Health care in the United States already consumes about 18% of GDP. Critics of the Affordable Care Act worry that by reducing price signals and market incentives in favor of greater reliance on government guarantees, health-care costs may rise even further, creating longer-run harms.

456