Signaling as a Response to Asymmetric Information

Hyundai Motor Company was founded in South Korea in 1967 and began selling cars in the United States in 1986. Hyundai cars were inexpensive and sold reasonably well but Hyundai was perceived as a low-quality brand with a poor repair history. Hyundai wanted to start producing more luxurious cars but they knew consumers wouldn’t buy if Hyundai couldn’t shake its low-quality reputation.

Hyundai attacked its problem with a two-pronged strategy. First, they invested in new, advanced factories, worker training, and quality control. If people bought their cars, Hyundai knew they would last but Hyundai couldn’t wait 10 years to prove its point. Hyundai had to get people to buy its cars now if all the new investments weren’t going to bankrupt the company. To solve its problem, Hyundai did something dramatic. In 1998, they introduced “America’s Best Warranty” on all their vehicles, 10 years/100,000 miles on the powertrain and 5 years/60,000 miles on everything else. Hyundai immediately gained 28 points in the JD Power Customer Satisfaction survey and the next year their sales increased by 82%, the largest jumps in the history of the industry.

A signal is an expensive action that is taken to reveal information.

Hyundai’s warranty served two purposes. First, if something does go wrong the warranty has value as insurance. But more importantly, the warranty signaled that Hyundai was serious about quality. In fact, what made Hyundai’s signal credible was that the only way Hyundai’s warranty could be profitable for the company is if its cars didn’t break down—that is, if the warranty wasn’t used very often!

Hyundai’s signal overcame an asymmetric information problem. Hyundai knew that it had greatly improved its production process but all the consumers had to go on was Hyundai’s less than stellar history. The signal worked because offering a warranty is cheap for a company that produces high-quality cars but expensive for a company that produces low-quality cars.

Signaling in the Job Market

You are an aspiring software programmer and you see the perfect job being advertised in Silicon Valley at a starting salary of $90,000 a year. Awesome! You really want the job and, remembering your economics lesson that incentives matter, you tell the interviewer that you would be willing to take the job for just $75,000. You are confident that you have underbid the other applicants and so will get the job. You don’t get the job. What happened? Your reasoning about the power of underbidding is correct if the interviewer can easily evaluate the quality of all the job candidates. Who wouldn’t want high quality at a low price? But evaluating job candidates is notoriously difficult. Some candidates who look good on paper are disasters in practice, and vice versa. The interviewer doesn’t know your true quality. As a result, when the interviewer hears your offer to work for much less, the interviewer may infer that you are desperate—a low-quality candidate who can’t get a job elsewhere—not someone the company wants to hire. Once again, this is a problem of adverse selection: The interviewer is worried that the people who most want the job are not the people the firm most wants to hire. This is one reason why unemployed people often find it harder to get hired than do similar employed workers looking for a new job.

Offering to work for low pay sends a signal that you might be a low-quality worker. How could you signal a potential employer about your high quality? Here’s a hint: You might be signaling right now. We hope that you are learning something from this textbook that will be useful to you in your future career. One theory of education, however, says that education pays not because it offers any practical advice but only because a degree is a signal of IQ and conscientiousness, including grit and determination.

457

As professional academics, we have in fact noticed that not every degree actually prepares people for the real world. A lot of study seems to consist of relatively academic exercises with few practical applications. Some degrees do pay more, including chemical engineering and economics! But if you graduate with a degree in art or ancient Greek history, don’t despair. Most degrees pay even if your eventual job has nothing to do with your degree. Signaling helps explain why. It’s easier for someone with a high IQ and good work habits to get a degree—almost any degree—than it is for someone with a low IQ and a lack of determination. Thus, completing a degree signals to employers that you are likely to have the kinds of qualities that employers are willing to pay for.

Consider the following thought experiment. Which do you think would pay more, a diploma from Harvard without a Harvard education or a Harvard education without the diploma? There is some evidence for the former. If education were only about learning and not at all about signaling, you would expect that people who took all the courses except one would receive almost as big a boost in their wages as a person who took all the courses and graduated with a diploma. After all, the two individuals have nearly the same education. And yet people with a degree earn much more than people with nearly the same education but without the degree. In the literature, this is called the “sheepskin effect” (degrees were made of sheepskin a long time ago) because it says that the sheepskin you hang on the wall is worth a large fraction of the value of the education.9 The lesson here is to finish your degree!

Signaling in Dating, Marriage, and the Animal Kingdom

Signaling pervades our lives, and it is not restricted to narrowly economic transactions. Criminals, for example, often need to signal to each other their propensities to break the law, yet without incriminating themselves should they be dealing with an undercover police officer. Facial tattoos are one way to do this because the tattoo shows the person has given up on any chance of achieving a normal, mainstream life. In South African prisons, for instance, such tattoos are a common way for true criminals to identify each other and verify that they really are disreputable lawbreakers. One South African prisoner had the phrase “Spit on my grave” tattooed across his forehead and “I hate you, Mum” imprinted on his left cheek. That’s a pretty good sign that a person is not looking to go straight or to reform and enter mainstream life.10

Employers interview potential employees extensively because it’s much cheaper to avoid hiring a bad employee than it is to fire one. It’s also much cheaper to avoid marrying a bad partner than it is to divorce one. Thus, you can think of dating as a series of marriage interviews! As with a job interview, marriage interviews contain a lot of signaling.

Recall the aspiring programmer who offers to work for less money. The programmer’s offer is rejected because employers fear that someone who is so desperate for work that they offer to work for less is actually worth less. In this respect, getting a job and getting a date are not so different. Dating experts—not just economists—recommend, for example, that for both men and women, it’s important not to look too eager.

Engagement rings are a signal of our commitment to our partners or potential partners but in order to work they have to be expensive. An expensive ring is a signal because expensive rings are cheaper if you truly expect to remain married! If you think that rings are bought because they are beautiful rather than for signaling, consider the following thought experiment. How long would the tradition of giving a diamond engagement ring last if a new technology made diamonds cheap?

RICHARD I’ANSON/LONELY PLANET IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

458

Many women, when they marry, face the choice of whether to take the last name of their husband or perhaps to adopt a joint, hyphenated last name. If the woman takes the last name of her husband, it is a signal that a future divorce will be especially costly to her. She would then either be stuck with the last name of a man she has fallen out of love with, or she would have to change her name once again, which could make it harder to establish or keep a reputation and create costs for her professional life. On the other hand, if a woman keeps her maiden name, she is signaling a strong attachment to building or maintaining a career reputation. Some women try to have it both ways by using two names (one at the workplace, the other at home) or by using hyphenated names, while many other people wonder why this burden of adjustment is distributed so fully on women and not on men.

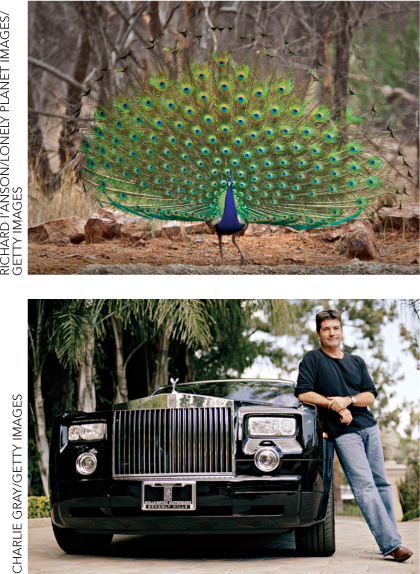

Signaling even pervades the animal kingdom. Charles Darwin was perplexed by the peacock’s tail. Why would a peacock use so many of its resources on a tail that not only didn’t help it survive but that actually hindered survival by making it more difficult for the peacock to escape predators? The theory of signaling and sexual selection offers an answer. Since only the healthiest and most robust peacocks can grow large and beautiful tails, the peacock’s tail signals to peahens that the peacock is healthy, has good genes, and would make a good partner for procreation.

Is Signaling Good?

Signaling creates benefits by generating information, but in most signaling models there is some inefficiency. It takes at least four years to get a degree, and if education doesn’t add much to future productivity, then that’s four years of effort just to signal IQ and perseverance. Maybe you have fun during the university years but university can’t be too much fun or everyone would do it, even those without high IQs and perseverance. Ideally, there might be a cheaper way to communicate this information to potential employers. We see the same issues with diamond rings. If there were a cheaper way to signal commitment, you could get your partner a much cheaper cubic zirconia ring and use the savings to buy a nice Viking refrigerator. Solving these problems isn’t easy, however. We are both professors of economics and believe us when we say that we didn’t even try to eliminate the costs of signaling with diamond rings.

Finally, note that while signaling eases some problems of asymmetric information, it creates others. In particular, when signaling is rife, some moral hazard problems may become worse. Let’s go back to education as a signal of worker productivity. If finishing an education gets you higher wages whether or not you learn anything useful, that sad reality removes some of the pressure on colleges and universities to teach you something useful. Students might prefer to learn something practical rather than just jumping through hoops, but professors will find it easier to teach what interests them and many administrators will tolerate this. After all, conscientious students will still attend and finish college simply to get the higher wages, whether or not they learn very much. We return again to a key theme of this chapter: many asymmetric information problems can be eased or traded in for easier-to-handle substitute information problems, but asymmetric information will continue as a general market phenomenon.

459