29 Saving, Investment, and the Financial System

175

CHAPTER OUTLINE

The Supply of Savings

The Demand to Borrow

Equilibrium in the Market for Loanable Funds

The Role of Intermediaries: Banks, Bonds, and Stock Markets

What Happens When Intermediation Fails?

The Financial Crisis of 2007–2008: Leverage, Securitization, and Shadow Banking

Takeaway

Appendix: Bond Pricing and Arbitrage

The world’s financial system was shaken to its core when on September 15, 2008, the investment bank Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. The Lehman bankruptcy was by far the largest in history. To give you some idea, when it went bankrupt Lehman had assets worth $691 billion; when GM went bankrupt several years later it had assets worth just $91 billion. The Lehman bankruptcy shook the financial world, however, not simply because it was large but because Lehman Brothers was an important financial intermediary, an institution that works to transform savings into investments.

Lehman Brothers failed because it had lost billions on buying and betting on mortgage securities. So had many other banks and financial institutions. When Lehman failed, many people wondered: Who was next? No one wanted to lend money to a firm that might soon go bankrupt. As a result, credit dried up for firms in many sectors, throwing the American economy and indeed the world economy into what was the scariest moment in many decades, arguably since the Great Depression of the 1930s. This episode is sometimes called the collapse of the “shadow banking system,” a term that we will examine in more detail later in this chapter, but we might also call it the collapse of the financial intermediaries.

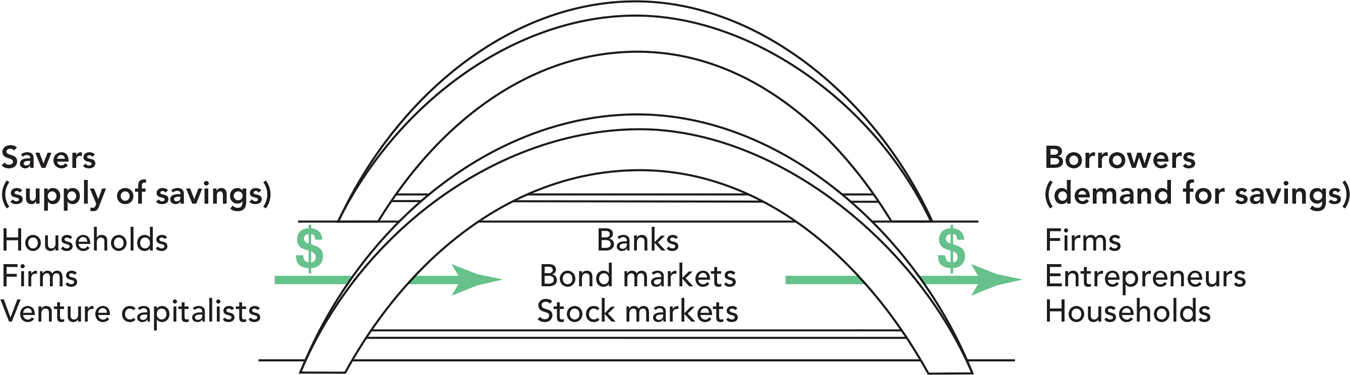

This chapter is about savers and borrowers and some of the financial intermediaries—banks, bond markets, and stock exchanges—that bridge the gap between savers and borrowers, as we illustrate in Figure 29.1. We have opened the chapter with a scary story about what can happen when financial intermediaries fail. Fortunately, the collapse of Lehman was an extreme episode and there are plenty of other cases where intermediation works quite smoothly, to the benefit of all parties involved. Recall from Chapter 27 and Chapter 28 that savings are necessary for capital accumulation, and the more capital an economy can invest, the greater is GDP per capita. So transforming savings into investment is important. More generally, connecting savers and borrowers increases the gains from trade and smooths the process of economic growth.

176

Saving is income that is not spent on consumption goods.

Before proceeding, let’s make it clear what we mean by the words saving and investment. Saving is income that is not spent on consumption goods. Investment is the purchase of new capital, things like tools, machinery, and factories. It’s important to see that the way economists define investment is not the same as the way a stockbroker defines investment. If Starbucks buys new espresso machines for its stores, that’s investment. If John buys stock in Starbucks, that is not investment in the economic sense but merely a transfer of ownership rights of already existing capital (see Chapter 23 for a treatment of how individuals should allocate their funds for their personal “investments”). Most of the trading on stock exchanges is thus not investment in the economic sense because it simply transfers ownership of a stock from one person to another. From an economic point of view, investment requires a purchase of new capital.

Investment is the purchase of new capital goods.

Ok, let’s see how savings are mobilized and transformed into investment. We will be using the economist’s tools in trade—supply and demand—and we’ll start with the supply of savings. This is important material in its own right and it also supplies building blocks for understanding banks, bank failures, and what went wrong in the global financial crisis of 2007–2008.