The Supply of Savings

We begin with the left side of Figure 29.1, the supply of savings. Economists have a good but imperfect understanding of what determines the supply of savings. Here are four of the major factors: smoothing consumption, impatience, marketing and psychological factors, and interest rates.

177

Individuals Want to Smooth Consumption

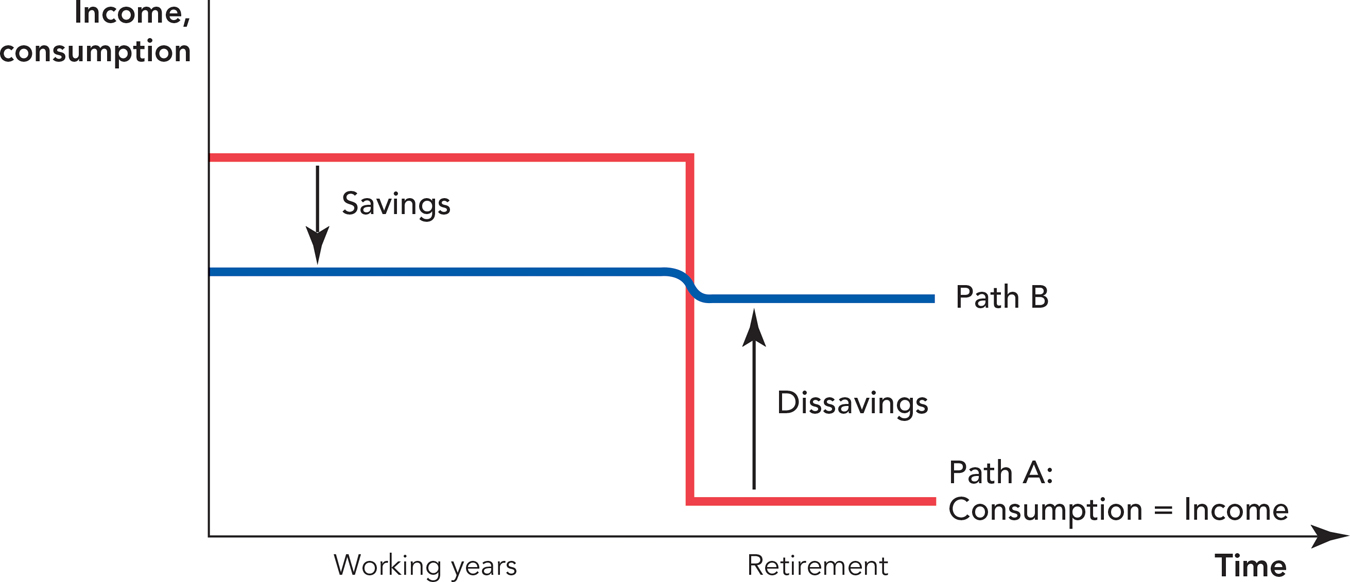

If you consumed what you earned every year, your consumption over time might look like Path A in Figure 29.2. Along Path A, consumption is equal to income. Consumption is high during your working years, but after retirement consumption drops precipitously—as a result, once you retire and your income falls, you must sell the nice car and give up the fancy lifestyle just to scrape by. Most people would prefer consumption Path B. Along Path B, consumption is less than income during the working years because you save for retirement. But when retirement comes, consumption is greater than income as you spend your savings, or “dissave.”

Economists say that Path B is “smoother” than Path A. The desire to smooth consumption over time is a reason to save and, as we will discuss shortly, also a reason to borrow.

The consumption–smoothing theory of saving can tell us something important about AIDS, Africa, and economic growth. Remember from previous chapters that savings are necessary to finance the capital accumulation that generates high standards of living. If there are no savings, investment dries up, economic growth declines, and the standard of living falls.

Now consider that AIDS has dramatically reduced life expectancy in Africa. What is your prediction about savings rates? Imagine that you expected to die in a few years—would you save much? Probably not. Similarly, many poorer Africans don’t save much because, sadly, they expect to die young.1 This gives rise to a vicious cycle. The decline in life expectancy caused by AIDS reduces saving rates, which in turn reduces economic growth and the standard of living, and that makes it more difficult to combat diseases like AIDS.

Fluctuations in income are another reason why people save. Some workers, such as salespeople, writers, and home builders, have incomes that fluctuate from year to year. Most workers could have unexpected health problems or they could find themselves unemployed and so they also fear that their income might fluctuate. By saving in the good years, workers can build a cushion of wealth to draw from in the bad years, thereby smoothing their consumption across all years.

178

Individuals Are Impatient

Time preference is the desire to have goods and services sooner rather than later (all else being equal).

Another reason why people save, or fail to save, is their level of impatience. Most individuals prefer to consume now rather than later so saving is not always easy. Some people, however, are very impatient; others less so. This is what economists call time preference. Time preference reflects the fact that today feels more real than tomorrow. The more impatient a person, the more likely that person’s savings rate will be low.

Impatience is reflected not just in savings but in any economic situation where people must compare costs and benefits over time. The cost of a college degree, for example, comes well before the benefit. To get a college degree, you must pay for tuition and books and, most important, you must give up the income that you could earn from a job, all right now. The benefits of a college degree are large—a typical college graduate will earn nearly twice as much as a typical high school graduate—but the benefits are all in the future. An impatient person will weigh the up-front costs highly and discount the future benefits. Impatient people are unlikely to go to college.

The Marshmallow Test

http://qrs.ly/354ard7

Crime is another economic activity with immediate benefits and future costs so it’s not surprising that criminals tend to be impatient people. Similarly, heroin addicts, alcoholics, and smokers all tend to discount the future more heavily than nonaddicts.

Impatience depends, in part, on circumstances and, in part, on the person. In one fascinating study, four-year-old children were offered one marshmallow now or two if they could wait for the tester to return. Many years later, the children were evaluated again—the children who had waited were less impulsive and had higher grades than the children who had not waited.2

Marketing and Psychological Factors

Marketing matters, even for savings. Often individuals save more if saving is presented as the natural or default alternative. In one study, economists studied retirement savings plans. Some employers automatically enrolled all new employees in a retirement savings plan, leaving the employees the choice to opt out, whereas others required employees to request such an account, in effect asking them to opt in. In the businesses that used automatic enrollment, the savings plan participation rate was 25% higher than in the businesses where employees needed to request a retirement account.

The default also mattered for how much was saved. In one firm, the default savings rate was 3% of salary. More than a quarter of the workers chose that as their savings rate, despite an employer guarantee of a dollar-for-dollar match on contributions of up to 6% of salary. Later, the company switched to a 6% default savings rate; in that setting, hardly any new workers chose the 3% savings contribution rate even though they could have switched with just a phone call.3

It’s quite surprising how some simple psychological changes, combined with effective marketing and promotion, can change how much people save for their retirement. Behavioral economics, a new and growing field within economics, combines economics, psychology, and neurology to study how people make decisions and how they can be helped to overcome biases in decision making.

179

The Interest Rate

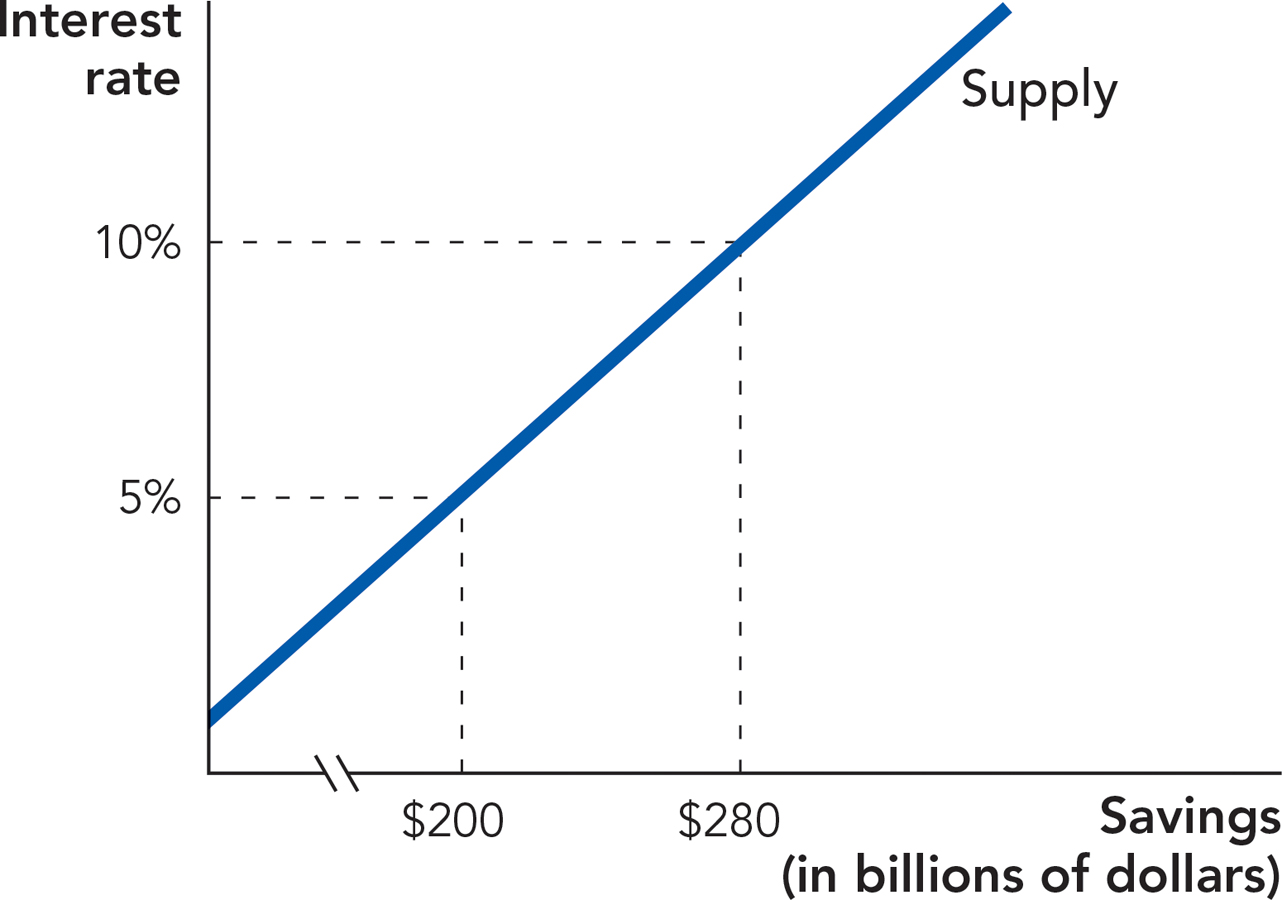

The quantity of savings also depends on the interest rate, namely how much savers are paid to save. If the interest rate is 5% per year, then $100 saved today returns $105 a year from now. If the interest rate is 10% per year, then $100 saved today returns $110 a year from now. All else being equal, higher interest rates usually call forth more savings.* Figure 29.3 shows the supply curve for savings. The vertical axis of Figure 29.3 measures the interest rate. The horizontal axis measures savings in dollars. In this example, an interest rate of 5% generates total savings of $200 billion and an interest rate of 10% generates total savings of $280 billion.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 29.1

Examining Figure 29.1, what is the crucial function that financial institutions perform?

Examining Figure 29.1, what is the crucial function that financial institutions perform?

Question 29.2

Financial advisors have warned that increased life expectancy means that many people have not saved enough for their retirement. If true, what will the consumption path of these people look like as they reach their retirement years? Will this consumption path be smooth?

Financial advisors have warned that increased life expectancy means that many people have not saved enough for their retirement. If true, what will the consumption path of these people look like as they reach their retirement years? Will this consumption path be smooth?

Question 29.3

Can you think of the other factors that might generate a demand to save? (Hint: Apart from retirement, what other factors could cause income to be volatile?)

Can you think of the other factors that might generate a demand to save? (Hint: Apart from retirement, what other factors could cause income to be volatile?)

You might wonder why the supply curve for savings has the interest rate on the vertical axis while other supply curves have had price on the vertical axis. In fact, interest rates are just a convenient way of expressing the price of savings. An interest rate of 5%, for example, means that the saver will be paid $5 (in one year) for every $100 saved. Thus, we could say that when the price of lending is $5 per $100 saved, the quantity of savings is $200 billion. It’s a bit easier, however, to think in terms of interest rates.

The bottom line is that the interest rate is a market price and it has the same properties of market prices that we discussed in the introductory chapters of this book.