The Demand to Borrow

Why do people borrow? People borrow to smooth their consumption path and especially to finance large investments. Let’s look at each of these reasons for borrowing.

Individuals Want to Smooth Consumption

Just as people save in order to smooth consumption, one reason people borrow is to smooth consumption. Many young people, for example, borrow so that they can invest in their education. If they had to pay their tuition expenses all at once, many students would have to sell their car or eat nothing but beans and oatmeal for a year. But if tuition payments can be made over many years, as borrowing makes possible, the sacrifices are spread out and become less painful. A student who can borrow can move some of the sacrifices into future periods when the (now former) student has a job and a regular income. Student borrowing is thus another example of how credit markets let people smooth their consumption over time.

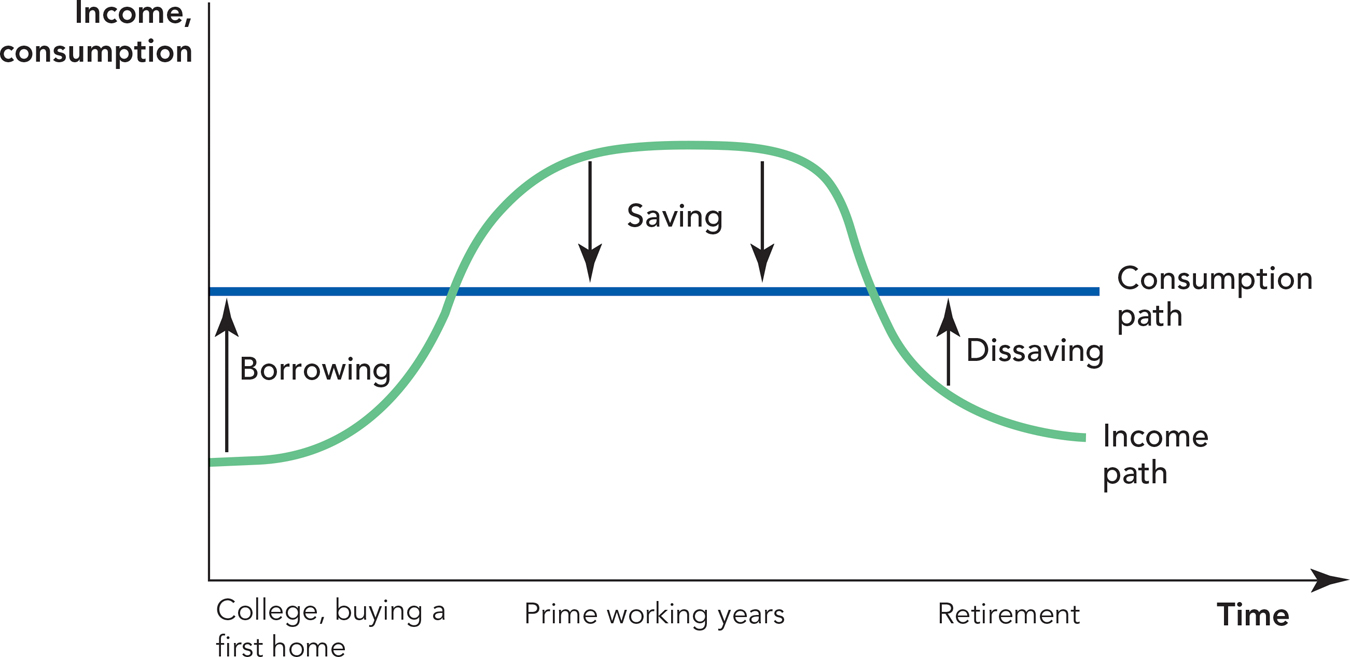

The “lifecycle” theory of savings, pioneered by Nobel Laureate Franco Modigliani, puts the demand to borrow and save together. The lifecycle theory is illustrated in Figure 29.4. Income starts out low during the college years and in the early work years. To finance college and to buy a first home, people borrow so their consumption is higher than their income. As workers enter their prime earning years, they save to pay off their college debt and mortgage and they prepare for retirement—during this time period consumption is less than income. As people get older and retire, consumption is once again above income as dissaving (i.e., using up savings) occurs. Overall, borrowing, saving, and dissaving help people to smooth out their consumption path over time—although few people would have a consumption path as smooth as the one we have drawn here!

180

Governments also borrow for reasons much like consumers. Governments may borrow, for example, to finance unusually large expenditures such as those required to pay for a war, or to pay for large investments such as the interstate highway system. We discuss government taxes, spending, and borrowing at greater length in Chapter 36.

Borrowing Is Necessary to Finance Large Investments

Businesses also borrow extensively. Many new businesses can’t get under way at all without borrowing. Often the people with the best business ideas are not the people with the most savings, so people with good ideas must borrow funds to start their careers as entrepreneurs.

Fred Smith, the legendary entrepreneur, first laid out the idea for FedEx in an undergraduate paper he had to write for an economics class. Smith’s idea, overnight delivery of packages using a hub and spoke system, was great but the problem was that he couldn’t start small. To be successful, Smith needed to cover a good part of the country from day 1 and he didn’t have enough of his own money to build an entire network. Smith began FedEx with 16 planes covering 25 cities using money he borrowed and also by selling part ownership of FedEx to venture capitalists, investors willing to accept risk in return for a stake in future profits. FedEx, of course, has been a huge success—it changed the way America does business and made Smith a very wealthy man. By the way, Smith’s grade on his paper: C!

181

More generally, businesses borrow to finance large projects. The costs of developing an apartment building are all up front; the revenues don’t start flowing until the building is completed and the tenants have moved in. In fact, it may take many years before the revenues fully cover all the up-front costs. If a developer like Donald Trump had to wait until he personally had enough funds to pay the up-front costs, he might be able to develop just one or two buildings in his lifetime. By borrowing, developers are able to invest now and develop many more buildings

The examples of borrowing that we have given share a common theme. A student who can’t borrow may not be able to get an education even though the education would be a good investment. A government that can’t borrow may not be able to invest in an interstate highway system even though the highway system would pay for itself many times over. A builder who can’t borrow may not be able to build an apartment building even though it would be a profitable investment. Thus, borrowing plays an important role in the economy—the ability to borrow greatly increases the ability to invest and, as shown in Chapter 27 and Chapter 28, higher investment increases the standard of living and the rate of economic growth.

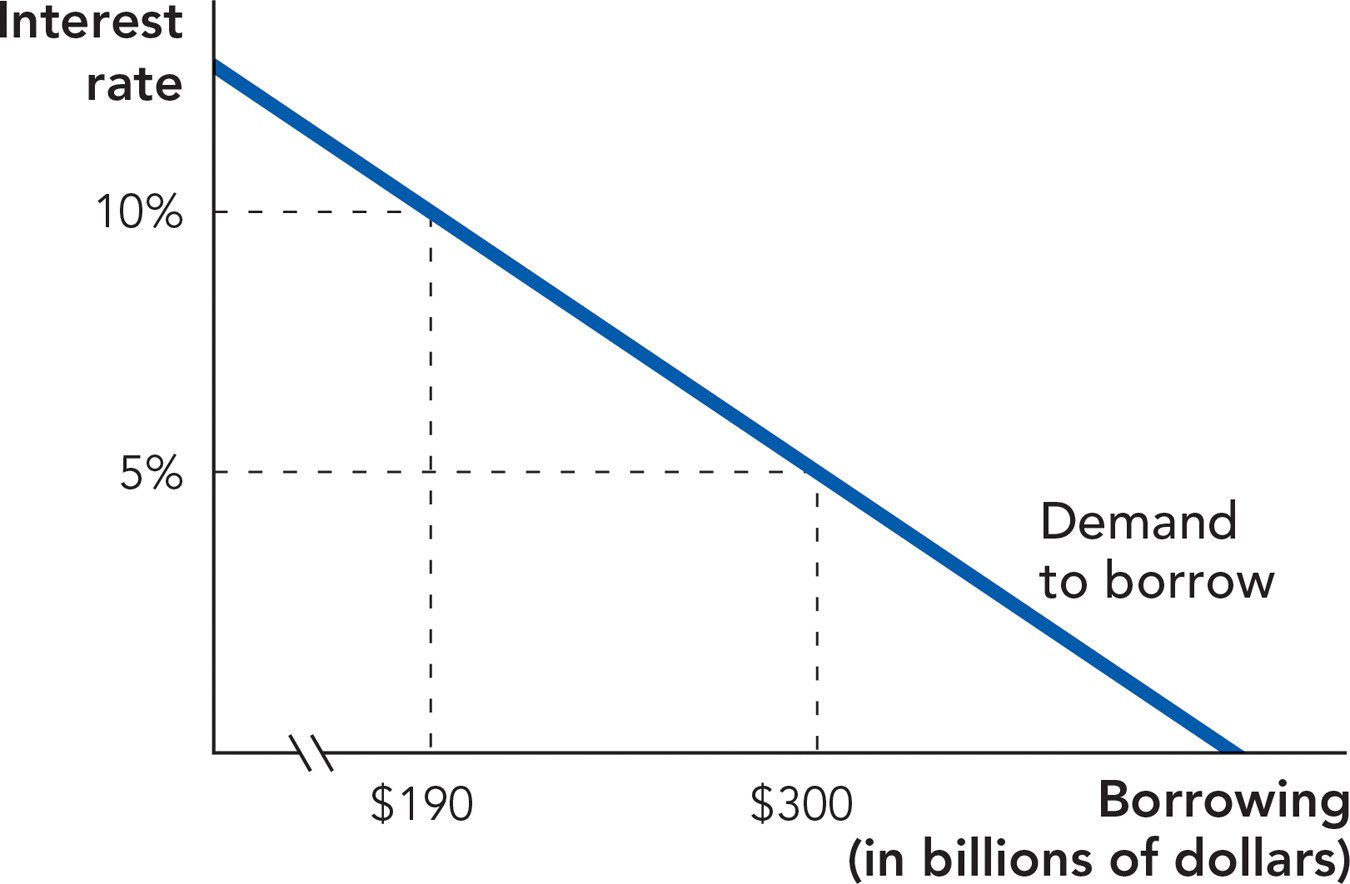

The Interest Rate

Of course, the quantity of funds that people want to borrow also depends on the cost of the loan, or the interest rate. Businesses, for example, borrow when they expect that the return on their investment will be greater than the cost of the loan. Thus, if the interest rate is 10%, businesses will borrow only if they expect that their investment will return more than 10%. If the interest rate is 5%, then businesses will only borrow if they expect that their investment will return more than 5%. Since more investments will return more than 5% than will return more than 10%, the demand to borrow follows the law of demand: The lower the interest rate, the greater the quantity of funds demanded for investment as well as for other purposes.

In Figure 29.5, $190 billion is demanded when the interest rate is 10% and $300 billion is demanded when the interest rate is 5%.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 29.4

Under the lifecycle theory, when is an individual’s savings likely to be at its peak?

Under the lifecycle theory, when is an individual’s savings likely to be at its peak?

Question 29.5

If interest rates fall from 7% to 5% (and all else is the same), what happens to the number of people buying homes? Starting businesses?

If interest rates fall from 7% to 5% (and all else is the same), what happens to the number of people buying homes? Starting businesses?

182