What Happens When Intermediation Fails?

Economic growth cannot occur without savings and those savings must be processed and intermediated through banks, bond markets, stock markets, and so on. Countries without these institutions have smaller markets for loans, use their savings less effectively, and make fewer good investments.4 But why do some countries have poorly developed banking and financial systems?

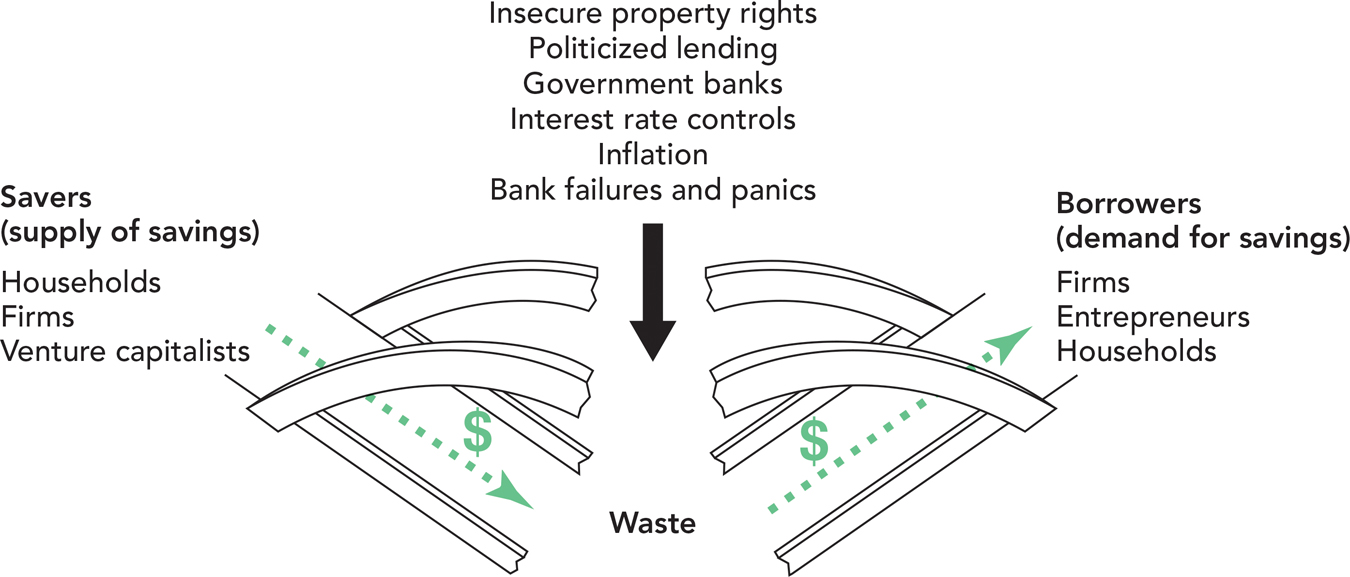

The bridge between savers and borrowers can be broken in many ways, including insecure property rights, inflation and controls on interest rates, politicized lending, and massive bank failures and panics. These problems can break the bridge by (1) reducing the supply of savings, (2) raising the cost of intermediation, and (3) reducing the effectiveness of lending. Figure 29.11 illustrates the main ideas.

FIGURE 29.11

Insecure Property Rights

Consider, for example, the supply of savings. The expected return on savings depends on more than just the posted rate of interest at the bank. Some governments do not offer secure property rights to savers. That is, saved funds are not immune from later confiscation, freezes, or other restrictions.

During the financial crisis beginning in December 2001, for example, the Argentine government partially froze bank accounts for a year. Many of the banks subsequently went under, which meant that Argentine citizens lost their bank-based savings. This event was not a complete surprise. The Argentine government had a history of freezing bank accounts, such as during 1982 and 1989. Other countries in the region, such as Brazil in 1990, had also frozen bank accounts. Obviously, this repeated pattern means that Argentines and Brazilians save less than they otherwise might wish to. Why save when those funds are simply being put up for grabs? Ana, a 40-year-old teacher from Argentina, kept her savings in dollars in her house and then exchanged them for pesos to pay her bills. She said, “You just can’t put your money in banks here.”5 Ana is right, but unlike money in the bank, which can be lent out to fund investment, money under a mattress does not contribute to economic growth.

If individuals expect that contracts will be broken, they will be reluctant to invest in stock markets as well. For instance, the Russian government often does not respect the rights of minority shareholders and at times it has confiscated or restricted the value of their shareholdings, as in the case of the private energy company Yukos. The result is that many foreign investors are unwilling to put money into Russian ventures. They simply do not trust the Russian government, nor do they believe that Russian courts will enforce contracts impartially.

Law is one side of the equation, but custom and informal trust are another. In a healthy economy, shareholders expect that managers are interested in building their long-run reputations, rather than ripping off the company at every possible opportunity. When managers look only to short-run gains, it is hard to run a business enterprise, as investors will not entrust managers with the control of resources. Systems of monitoring and accounting, no matter how well developed, cannot overcome high levels of mistrust. This is a common problem in developing countries around the world but the Enron, WorldCom, and Madoff scandals demonstrate that the United States is also not immune to such problems. Trust is an important asset throughout the world.

Controls on Interest Rates

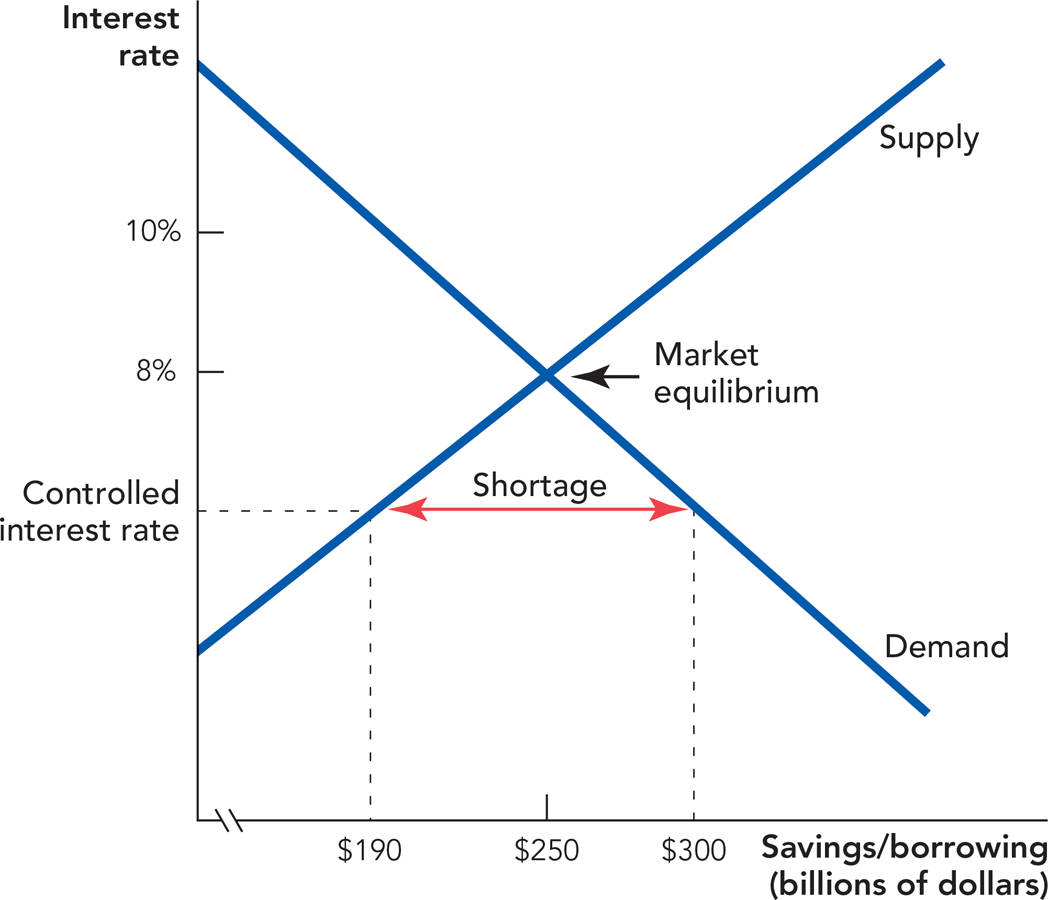

Price controls on interest rates also cause the loanable funds market to malfunction. Consider a maximum ceiling on the interest rate that can be charged on a loan. Sometimes economists call these ceilings “usury laws”; usury laws date back to medieval times and earlier. Today most American states have usury laws, although often they have loopholes (they don’t stop most credit card borrowing, for instance) or they are set at levels too high to influence most loan markets. Nonetheless, a binding and enforceable ceiling on interest rates would look like Figure 29.12.

FIGURE 29.12

The equilibrium is just like our analysis of price controls in Chapter 8. At the artificially low price, there is a shortage of credit, and many people who wish to borrow at the controlled interest rate cannot do so. Moreover, the control on interest rates reduces savings. In Figure 29.12, savings fall from $250 billion at the market equilibrium to just $190 billion at the controlled interest rate. Similarly, just as with price controls on oil, an interest rate control will cause a misallocation of savings and a loss of potential gains from exchange. Perhaps most important, investment, which is determined by the supply of savings, will fall below what it would be at the market equilibrium.

Politicized Lending and Government-Owned Banks

Japanese history from about 1990 to 2005 also illustrates the importance of banks in using a nation’s savings effectively. During this period, the Japanese continued to save, but Japanese economic growth was zero or negative for most of these years. How can this have been? Many Japanese banks were bankrupt or propped up by the government. They were not allocating funds efficiently. Other banks were pressured to lend money to well connected political allies, rather than to the most efficient new businesses. During this period, Japanese banks acted as storehouses for wealth, but they were not effective financial intermediaries. Japanese business innovation, and the Japanese standard of living, suffered accordingly.

In Japan, as in the United States, banks are privately owned so politicized lending, even when it occurs, is limited. But in many other countries, most large banks are owned by the government. Government-owned banks are useful to authoritarian regimes that use the banks to direct capital to political supporters. While it might be politically wise for the ruler to support his uncle’s firm, that uncle is probably not a superior entrepreneur. One important study by economists Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer found that the larger the fraction of government-owned banks a country had in 1970, the slower the growth in per capita GDP and productivity over the next several decades.6

Bank Failures and Panics

Systematic problems in the banking system usually lead to large-scale economic crises. At the onset of America’s Great Depression between 1929 and 1933, 11,000 banks—almost half of all U.S. banks—failed. The ripple effects were grim. Many people lost their life savings; they also had to curtail their spending, which meant that many businesses lost their customers and thus revenue. Many businesses were unable to get loans or daily working capital. Thus, bank failures were followed by a rash of small business failures. It took many years before the American banking system, and the American economy, recovered.

In their seminal work, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz argued that the Great Depression was brought about, in part, because the Federal Reserve—the U.S. central bank that is charged with overseeing the general health of the banking industry—failed in its job to prevent widespread bank failures.7 (See Chapter 32 for further discussion of the Great Depression and Chapter 34 for more on the Federal Reserve.) Economist Ben Bernanke later showed that one of the reasons why bank failures were so crucial in the onset of the Great Depression was because banks provide loans to a particular class of borrowers and lenders.8 According to Bernanke:

As the real costs of intermediation increased, some borrowers (especially households, farmers, and small firms) found credit to be expensive and difficult to obtain. The effects of this credit squeeze…helped convert the severe but not unprecedented downturn of 1929–30 into a protracted depression.

By the way, if you recognize Bernanke’s name, it is with good reason: He was chairman of the Federal Reserve between 2006 and 2014 when he had to face the worst intermediation crisis since the Great Depression.