CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 31.9

1. What is a “price level”? If the “price level” is higher in one country than another, what does that tell us, if anything, about the standard of living in that country?

Question 31.10

2. What are some forces that could cause shocks to v, the velocity of money?

Question 31.11

3. When is the inflation rate more likely to have a big change either up or down: when inflation is high or when it is low?

Question 31.12

4. Who gets helped by a surprise inflation: people who owe money or people who lend money?

Question 31.13

5. Who is more likely to lobby the government for fast money growth: people who have mortgages or people who own banks that lent money for those mortgages?

Question 31.14

6. Consider the interaction between inflation and the tax system (assume the inflation is expected). Does high inflation encourage people to save more or discourage saving? If a government wants to raise more tax revenue in the short run, should it push for higher or lower inflation?

Question 31.15

7. Which tells me more about how many more goods and services I can buy next year if I save my money today: the nominal interest rate or the real interest rate? Which interest rate gets talked about more in the media?

Question 31.16

8. If everyone expects inflation to rise by 10% over the next few years, where, according to the Fisher effect, will the biggest effect be: on nominal or real interest rates?

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 31.17

1. Calculate inflation in the following cases:

|

Price Level Last Year ($) |

Price Level This Year ($) |

Inflation Rate |

|---|---|---|

|

100 |

110 |

|

|

250 |

300 |

|

|

4,000 |

4,040 |

|

Question 31.18

2. What does the quantity theory of money predict will happen in the long run in these cases? According to the quantity theory, a rise in the money supply can’t change v or Y in the long run, so it must affect P. Let’s use that fact to see how changes in the money supply affect the price level. Fill in the following table:

|

M |

v |

P |

Y |

|---|---|---|---|

|

150 |

5 |

|

50 |

|

200 |

5 |

|

50 |

|

100 |

5 |

|

50 |

Question 31.19

3. In the long run, according to the quantity theory of money, if the money supply doubles, what happens to the price level? What happens to real GDP? In both cases, state the percentage change in either the price level or real GDP.

Question 31.20

4. Much of the economic news we read about can be reinterpreted into our “Mv = PY” framework. Turn each of the following news headlines into a precise statement about M, v, P, or Y:

“Deposits in U.S. banks fell in 2015.”

“American businesses are spending faster than ever.”

“Prices of most consumer goods rose 12% last year.”

“Workers produced 4% more output per hour last year.”

“Real GDP increased 32% in the last decade.”

“Interest rates fall: Consumers hold more cash.”

267

Question 31.21

5. It’s time to take control of the Federal Reserve (which controls the U.S. money supply). In this chapter, we’re thinking only about the “long run,” so Y (real GDP) is out of the Fed’s control, as is v. The Fed’s only goal is to make sure that the price level is equal to 100 each and every year—that’s just known as “price stability,” one of the main goals of most governments.

In question 2, you acted like an economic forecaster: You knew the values of M, v, and Y and had to guess what the long-run price level would be. In this question, you will act like an economic policymaker: You know the values of v and Y, and you know your goal for P. Your job is to set the level of M so that you meet your price-level target.

In some years, there will be long-lasting shocks to v and Y, so your job as a policymaker is to offset those shocks by changing the supply of money in the economy. Some of these changes might not make you popular with the citizens, but they are part of keeping P equal to the price-level target. Fill in the following table:

|

Year |

M |

v |

= |

P |

Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

25,000 |

2 |

|

100 |

500 |

|

2 |

|

4 |

|

100 |

500 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

100 |

400 |

|

4 |

|

4 |

|

100 |

200 |

|

5 |

|

2 |

|

100 |

400 |

|

6 |

|

1 |

|

100 |

600 |

Question 31.22

6. Nobel laureate Milton Friedman often said that “inflation is the cruelest tax.” Who is it a tax on? More than one answer may be correct:

People who hold currency and coins in their wallet, purse, or at home

Businesses that hold currency and coins in their cash registers

People or businesses who keep deposits in a checking account that pays zero interest

People or businesses who keep deposits in a savings account that pays an interest rate higher than the rate of inflation

People or businesses who invest in gold, silver, platinum, or other metals

Question 31.23

7. In countries with hyperinflation, the government prints money and uses it to pay government workers. How is this similar to counterfeiting? How is it different?

Question 31.24

8. The Fisher effect says that nominal interest rates will equal expected inflation plus the real equilibrium rate of return:

i = Eπ + r Equilibrium

i = Nominal interest rate

Eπ = Expected inflation rate

rEqiiilibrimn = Equilibrium real rate of return

Economists and Wall Street experts often use the Fisher effect to learn about economic variables that are hard to measure because when the Fisher effect holds, if we know any two of the three items in the equation, we can calculate the third. Sometimes, for example, economists are trying to estimate what investors expect inflation is going to be over the next few years, but they have good estimates only of nominal interest rates and the equilibrium real rate. Other times, they have good estimates of expected inflation and today’s nominal interest rates, and want to learn about the equilibrium real rate. Let’s use the Fisher effect just as the experts do: Use two known values to learn about the unknown third one.

|

i |

Eπ |

r Equilibrium |

|---|---|---|

|

5% |

2% |

3% |

|

5% |

1% |

|

|

5% |

|

8% |

|

|

10% |

2% |

|

6% |

|

2% |

|

0% |

−2% |

|

Note: The last entry is an example of the “Friedman rule,” something that we’ll come back to in a later chapter.

CHALLENGES

Question 31.25

1. If I get more money, does that typically make me richer? If society gets more money, does it make society richer? What’s the contradiction?

Question 31.26

2. Why is it so painful to get rid of inflation? Why can’t the government just stop printing so much money?

268

Question 31.27

3. Who gets hurt most in the following cases: banks, mortgage holders (i.e., homeowners), or neither?

|

Eπ |

π |

Who gets hurt? |

|---|---|---|

|

4% |

10% |

|

|

10% |

4% |

|

|

−3% |

0% |

|

|

3% |

6% |

|

|

10% |

10% |

|

Question 31.28

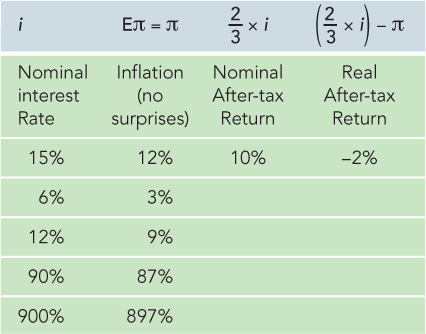

4. Let’s see just how much high expected inflation can hurt incentives to save for the long run. Let’s assume the government takes about one-third of every extra dollar of nominal interest you earn (a reasonable approximation for recent college graduates in the United States). You must pay taxes on nominal interest—just like under current U.S. law—but if you’re rational, you’ll care mostly about your real, after-tax interest rate when deciding how much to save.

To make the economic lesson clear, note that in every case, the real rate (before taxes) is an identical 3%. In each case, calculate the nominal after-tax rate of return and the real after-tax rate of return. Notice that as inflation rises, your after-tax rate of return plummets.

!launch! WORK IT OUT

What does the quantity theory of money predict will happen in the long run in these cases? According to the quantity theory, a rise in the money supply can’t change v or Y in the long run, so it must affect P. Let’s use that fact to see how changes in the money supply affect the price level. Fill in the following table:

|

M |

v |

P |

Y |

|---|---|---|---|

|

100 |

5 |

|

50 |

|

150 |

5 |

|

50 |

|

50 |

5 |

|

50 |

269