CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 34.11

1. Let’s find out what counts as money. In this chapter, we used a typical definition of money: “a widely accepted means of payment.” Under this definition, are people using “money” in the following transactions? If not, why not?

Lucy sells her Saab to Karen for $1,000 in cash.

Lucy sells her Saab to Karen for $1,000 worth of old Bob Dylan records.

Lucy sells her Saab to Karen for $1,000 in checking account balances (transferred by writing a check).

Lucy sells her Saab to Karen by Karen promising $1,000 worth of auto detailing services over the next year.

Lucy sells her Saab to Karen for $1,000 worth of Revolutionary War—era continental dollars.

Question 34.12

2. Define the following:

The monetary base, MB

M1

M2

Question 34.13

3.

Suppose that banks have decided they need to keep a reserve ratio of 10%—this guarantees that they’ll have enough cash in ATM machines to keep depositors happy, and enough electronic deposits at the Federal Reserve so that they can redeem checks presented by other banks. What is the money multiplier in this case?

If depositors start visiting the ATM a lot more often, will banks want to have a higher reserve ratio or a lower reserve ratio? Will this increase the money multiplier or lower it?

Page 333

Question 34.14

4. If the Federal Reserve wants to lower interest rates via open market operations, should it buy bonds or should it sell bonds?

Question 34.15

5. Practice with money multipliers. Think of the “money supply” (MS) as equal to either Ml or M2.

RR = 5%, Change in reserves = $10 billion. MM = ?; Change in MS = ?

RR = ?, Change in reserves = $1,000, MM = 5, Change in MS = ?

RR = 100%, Change in reserves = $10 billion. MM = ?, Change in MS = ?

Question 34.16

6. In the previous question, one example assumed that banks kept a 100% reserve ratio. Some economists have recommended that all banks be required by law to keep 100% of their deposits in the bank vault, at the Federal Reserve, or invested in ultrasafe investments such as short-term U.S. Treasury bills.

If this happened, what would the money multiplier be equal to?

If this happened, would the interest rate on bank deposits probably go up or down?

If this happened, would people be more likely or less likely to invest their savings in bank alternatives, such as bonds, mutual funds, or their cousin’s lawn mowing business?

Question 34.17

7. The main interest rate that the Federal Reserve tries to control is the Federal Funds rate, the interest rate that banks charge on short-term (usually overnight) loans to other banks. Let’s see how much interest a bank can earn if it lends money at the Federal Funds rate.

Virginia Community Bank has $2,000,000 of extra cash sitting in its account at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. It gets a call from Bank of America asking to borrow the whole $2,000,000 for 24 hours. (This is typical: It’s usually the smaller banks lending money overnight to the bigger banks.)

If the annual interest rate on federal funds is 4%, what (approximately) is the one-day interest rate on federal funds? (Note that interest rates, like GDP growth rates, are usually reported as “per year,” just as speeds are reported as miles “per hour.”)

How many dollars of interest will Virginia Community Bank earn for lending this money for one day?

If Virginia Community Bank lent this amount every day at the same rate for an entire year, how much interest would it earn?

Question 34.18

8. Let’s use the model of the supply and demand for bank reserves to explain how the Federal Reserve can change aggregate demand in the short run. Remember that the Federal Reserve controls the supply of bank reserves, but private banks create demand for bank reserves.

After a meeting, the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee votes to cut interest rates from 2% to 1.5%. How will they make this happen: Will they increase the supply of reserves or decrease the supply?

As a result of your answer to part a, will banks usually lend more money in response, or will they lend less money? Will this tend to increase the nation’s money supply, lower it, or will it have no net effect on the money supply?

Will this typically increase aggregate demand or lower it?

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 34.19

1. Whether an asset is “liquid” often depends on what situation you are in. For each of the following pairs of assets, which is more liquid in the particular setting?

You want to buy a sofa:

A savings account or currency

You want to trade for a bologna sandwich in elementary school:

A peanut butter and jelly sandwich or sushi

You want to buy a house:

Currency or a checking account

You live in a postapocalyptic wasteland:

Rice or currency

You are traveling across Europe during the Middle Ages:

Gold coins or works of art

You are an investment banker buying a corporation:

U.S. Treasury bonds or currency

Question 34.20

2.

Who is more likely to take bigger risks: a trapeze artist with a safety net underneath or a trapeze artist without a safety net?

Who is more likely to take bigger risks with his deposits: a bank CEO in a country where there is a lender of last resort or a bank CEO in a country where there is no lender of last resort?

Who is more likely to spend more time searching for a well run, safe bank: a depositor living in a country with government-run deposit insurance or a depositor living in a country without government-run deposit insurance?

Do government-run central banks and deposit insurance both increase moral hazard problems, both decrease moral hazard problems, or do they push in different directions when it comes to moral hazard?

Question 34.21

3.

In the short run, if the Fed wants to cut short-term, nominal interest rates, what does it do: Does it increase the growth rate of money or decrease the growth rate of money? Why? Will this tend to lower the real rate or will it tend to lower inflation?

In the long run, if the Fed wants to cut short-term, nominal interest rates, what does it do: Does it increase the growth rate of money or decrease the growth rate of money? Why? Will this tend to lower the real rate or will it tend to lower inflation?

Question 34.22

4. Let’s watch a bank create money. Last Wednesday, the Bank of Numenor opened for business. The first customer, Edith, walked in the door with 100 silver coins called Thalers to deposit in a new checking account. The second customer, Max, walks in the door a few minutes later, asking to borrow 50 Thalers for a week. The bank lends Max the Thalers. Just to keep things simple, assume these are the only financial transactions in Numenor. And just to be clear: Thalers are either “currency” or “reserves”: Silver in Max or Edith’s hands is “currency,” while Thalers in the bank is “reserves.”

How much “money” is there in the Numenor economy before Edith walks into the bank?

Monetary base:

Ml:

How much “money” is there in the Numenor economy after Edith makes her deposit, but before Max walks in for his loan?

Monetary base:

M1:

How much “money” is there in the Numenor economy after the Bank makes Max the loan?

Monetary base:

M1:

Which action created money: Edith’s deposit or Max’s loan?

Question 34.23

5. You are a bank regulator working for the Federal Reserve. It is your job to see whether banks are solvent or insolvent, liquid or illiquid. Fit each of the following banks into one of the following four categories:

Liquid and solvent (best)

Illiquid but solvent (probably needs short-term loans from other banks or from the Fed)

Liquid but insolvent (should be shut down immediately: could fool people for a while if not for your good efforts)

Illiquid and insolvent (should be shut down immediately)

Bank of DelMarVa

Short-term assets

Short-term liabilities

$10 million

$6 million

Total assets

Total liabilities

$40 million

$50 million

Bank of Escondido

Short-term assets

Short-term liabilities

$6 million

$10 million

Total assets

Total liabilities

$50 million

$40 million

Bank of Previa

Short-term assets

Short-term liabilities

$12 million

$10 million

Total assets

Total liabilities

$50 million

$40 million

Page 335Bank of Cambia

Short-term assets

Short-term liabilities

$8 million

$10 million

Total assets

Total liabilities

$30 million

$40 million

Bank of Marshall

Short-term assets

Short-term liabilities

$120 million

$100 million

Total assets

Total liabilities

$500 million

$400 million

Question 34.24

6. We mentioned that banks are reluctant to borrow from the Fed’s discount window because it’s looked down on by other banks: Other banks think that if a bank needs to use the discount window, it’s probably not very healthy. So where you get your loans is a signal about what kind of bank you are. Which of the following would seem like bad signs? If you think one or more of the cases are ambiguous, explain.

Your friend borrows money from a federal student loan program.

Your friend borrows money from a payday loan store.

Your friend pays for ordinary living expenses by borrowing with her credit card.

Your friend borrows money from her parents.

Your friend borrows money from an illegal loan shark.

Question 34.25

7. Does the House of Representatives get to vote on who becomes the chairperson of the Federal Reserve Board? If not, who does get to vote?

CHALLENGES

Question 34.26

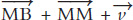

1. We mentioned how difficult it can be for the Federal Reserve to actually control aggregate demand: Its control over the broader money supply (Ml and M2) is weak and indirect, plus it can’t control velocity very much at all. Let’s translate the following bullet points from the chapter into an expanded aggregate demand equation. You know that increasing AD means increasing spending growth,  , but now you know that M (growth in M1 or M2, money measures that include checking accounts) depends on growth in the monetary base (MB) and on the money multiplier (MM). That means an increase in AD requires an increase in

, but now you know that M (growth in M1 or M2, money measures that include checking accounts) depends on growth in the monetary base (MB) and on the money multiplier (MM). That means an increase in AD requires an increase in  .

.

Let’s apply this fact to the following cases mentioned in the chapter. In all cases, the Federal Reserve is trying to boost AD by raising  . But if there’s a fall in

. But if there’s a fall in  or a fall in

or a fall in  at the same time, the Fed’s actions might do nothing to AD. In each case below, what are we concerned about: a fall in

at the same time, the Fed’s actions might do nothing to AD. In each case below, what are we concerned about: a fall in  or a fall in

or a fall in  ?

?

Will banks lend out all the new reserves or will they lend out only a portion, holding the rest as excess reserves?

Will increases in the monetary base translate into new bank loans?

If businesses do borrow, will they promptly hire labor and capital, or will they just hold the money as a precaution against bad times?

Question 34.27

2. In the past, the Federal Reserve didn’t pay interest on reserves kept in Federal Reserve banks: For an ordinary U.S. bank, money kept at the Fed earned zero interest, just like money stored in a vault or in an ATM machine. In 2008, the Fed started paying interest on deposits kept at the Fed.

Once the Fed started paying interest, what would you predict would happen to demand for reserves by banks: Would they demand more reserves or fewer reserves from the Fed?

If a central bank starts paying interest on reserves, will private banks tend to make more loans or fewer loans, holding all else equal? (Hint: Does the opportunity cost of making a car loan rise or fall when the central bank starts paying interest on reserves?)

Let’s put parts a and b together, keeping in mind the fact that bank loans create money. That means your answer to part b also tells you about the money supply, not just about the loan supply. If a central bank starts paying interest on reserves, will the reserve ratio chosen by banks tend to rise or fall? And will the money multiplier tend to rise or fall?

Page 336Your answer to part c tells us that when the central bank starts paying interest on reserves, there’s going to be a shift in Ml and M2, the broad forms of money supply that include money created through loans. But there are a lot of ways to affect the money supply, so if one force is pushing the money supply in one direction, we can find another tool to push the money supply in the opposite direction. Therefore, if a central bank chooses to start paying interest on reserves, but it wants M2 to remain unchanged, what should the bank do to the supply of reserves: Should it increase the supply of reserves or decrease the supply of reserves?

Question 34.28

3. Economist Bennett McCallum says that in order to push interest rates down in the long run, the central bank needs to raise interest rates in the short run. How can this be true?

WORK IT OUT

We mentioned that the central bank can influence a short-run real interest rate—this is because in the short run the inflation rate is relatively constant but the central bank can adjust the nominal rate on short-term loans. Recall that after investing in a T-bill, the real rate that investors receive is

Real interest rate = Nominal interest rate - Inflation

If inflation is 3% and the Fed wants the real rate on short-term loans to be 2%, what should it set the nominal Fed Funds rate equal to?

If inflation is 3%, and the Fed wants to encourage borrowing by cutting the real rate on short-term loans to -l%, what should it set the nominal Fed Funds rate equal to?

If inflation is 6%, and the Fed wants to discourage borrowing by raising the real rate on short-term loans to 4%, what should it set the nominal Fed Funds rate equal to?