CHAPTER 34 APPENDIX The Money Multiplier Process in Detail

Just to recap from the chapter, when the Federal Reserve conducts an open market operation, we said that the money supply changes by the change in reserves times the money multiplier, ΔMS = ΔReserves × MM. If the Fed buys government bonds, for example, this increases bank reserves, which increases the money supply by the increase in reserves times the money multiplier.

We’ve already mentioned the idea of a ripple effect: As one bank increases its loans, this leads to an increase in deposits in another bank, which in turn increases its loans, which leads to an increase in deposits in another bank, which increases its loans … and so forth.

Now it is time to look at this multiplier process in more detail.

It’s helpful to examine a simple form of accounting statement called a T-account. On the left side of a T-account, we list the bank’s assets, and on the right side, we list the bank’s liabilities. An asset is simply something that represents wealth or value to the bank. In our simple T-accounts, the only assets a bank can have are its reserves and its portfolio of loans. A liability refers to a debt or something owed to someone else. In our simple T-accounts, the only liabilities a bank can have will be deposits (the bank owes depositors the money in their accounts).

Now suppose that the Fed buys a government bond for $1,000 from a dealer in Treasury securities. The dealer has an account at the First National Bank and thus the Federal Reserve adds $1,000 to the dealer’s account. As a result, the First National Bank’s liabilities (its deposits) increase by $1,000, but the bank now also has an extra $1,000 in reserves. The First National Bank’s T-account looks like this:

|

First National Bank |

|

|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: +$1,000 |

Deposits: +$1,000 |

|

Loans: |

|

But what will the First National Bank do with its reserves? The bank wants to make a profit so it will take a portion of its reserves and lend them out. Suppose that the bank keeps $100 in reserves and lends out $900. The bank’s T-account now looks like this:

|

First National Bank |

|

|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: $100 |

Deposits: $1,000 |

|

Loans: +$900 |

|

338

Notice that the ratio of the bank’s reserves to deposits is $100/$1,000 or 0.1; thus, the reserve ratio = 0.1. Now the firm or person that borrowed the $900 did so to purchase goods and services. Let’s suppose that the borrower wrote a check for a cruise to Luxury Vacations Inc., which has an account at the Second National Bank. Luxury Vacations Inc. deposits the check into its account at the Second National Bank so the T-account of the Second National Bank now looks like this:

|

Second National Bank |

|

|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: +$900 |

Deposits: +$900 |

|

Loans: |

|

Notice that the Second National Bank’s reserves have increased by $900. What does the bank want to do with these reserves? Lend them! Suppose that the Second National Bank also wants a reserve ratio of 0.1 so the Second National Bank keeps $90 in reserves and lends out $810. Its T-account now looks like this:

|

Second National Bank |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

|

Reserves: $90 |

Deposits: $900 |

|

|

Loans: +$810 |

|

|

Are you beginning to see the multiplier in action? Let’s do one more. Suppose that the person or firm who borrowed money from the Second National Bank wanted the money to buy a computer. The borrower writes a check to Apple, which deposits the money in its account at the Third National Bank. The T-account of the Third National Bank now looks like this:

|

Third National Bank |

|

|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: +$810 |

Deposits: +$810 |

|

Loans: |

|

The Third National Bank also wants to make a profit, so it lends out a portion of its reserves, leading to a T-account like this:

|

Third National Bank |

|

|---|---|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: $81 |

Deposits: $810 |

|

Loans: +$729 |

|

339

So let’s summarize what we have so far:

|

The Banking System |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

|

|

Reserves |

Loans |

Deposits |

|

First National Bank |

+$100 |

+$900 |

+$1,000 |

|

Second National Bank |

+$90 |

+$810 |

+$900 |

|

Third National Bank |

+$81 |

+$729 |

+$810 |

|

… |

… |

… |

… |

Notice that the process doesn’t stop with the Third National Bank but continues onward. What is the final result of this process of expansion? Let’s focus on what is happening to deposits and see if we can get to the answer a little more quickly by figuring out the pattern.

At the First National Bank deposits increase by $1,000, at the Second Bank deposits increase by $900, or 0.9 × $1,000, at the Third Bank deposits increase by $810 or 0.92 × $1,000. If you guessed that at the Fourth Bank deposits would increase by $729 or 0.93 × $1,000, you are correct so the total process looks like this:

$1,000 × (1 + 0.9 + 0.92 + 0.93 + ...0.9n)

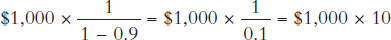

This is an example of an infinite geometric series and mathematics can show that (1 + 0.9 + 0.92 + 0.93 + ... 0.9n) converges to  so deposits will increase by

so deposits will increase by

The last expression should look familiar. Remember that we assumed in our derivations that each bank wanted a reserve ratio of 0.1 so the money multiplier MM = 1/RR = 10. Thus, the last statement says that deposits increase by the increase in reserves ($1,000) times the money multiplier, 10. The increase in the money supply can be measured by the increase in deposits. Thus, we have ΔMS = ΔReserves × MM, exactly as we said in the chapter. Aren’t you glad we saved the details for the appendix!

We can summarize by looking at how the initial increase in reserves created by the Fed open market purchase of bonds affects the entire banking system. A multiplier similar to that for deposits applies to reserves and loans so the final result looks like this:

340

|

The Banking System |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

|

|

Reserves |

Loans |

Deposits |

|

First National Bank |

+$100 |

+$900 |

+$1,000 |

|

Second National Bank |

+$90 |

+$810 |

+$900 |

|

Third National Bank |

+$81 |

+$729 |

+$810 |

|

… |

… |

… |

… |

|

Total |

$1,000 |

$9,000 |

$10,000 |

Note that we can measure the increase in the money supply by either the increase in the banking system’s assets, Reserves + Loans, or by the increase in the banking system’s liabilities, namely deposits. Thus, either way the money supply increases by the $10,000, or more generally ΔMS = ΔReserves × MM as we have said before.

Let’s make one qualification. In the multiplier process we went through, we assumed that every borrower wrote a check for every dollar of its loan and kept none of the money in cash. Thus, if a loan was made for $900, then somewhere in the banking system deposits increased by $900. If any of the borrowers keep some of their loan in cash, however, then the multiplier process does not operate on the cash component. For example, if a borrower receives a loan for $900 and writes a check for $800, keeping $100 in cash, then the multiplier process works only on the $800. Thus, the public’s demand for cash also influences the multiplier process and complicates the Fed’s job because the demand for cash can change over time.

) The headquarters of the 12 regional banks are located in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Richmond, Atlanta, Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Dallas, and San Francisco.