The Limits to Fiscal Policy

There are four major limits to fiscal policy. Three of these limits have to do with the difficulty of using fiscal policy to shift aggregate demand (AD).

Crowding out: If government spending crowds out or leads to less private spending, then the increase in AD is reduced or neutralized on net.

A drop in the bucket: The economy is so large that government can rarely increase spending enough to have a large impact.

A matter of timing: It can be difficult to time fiscal policy so that the AD curve shifts at just the right moments.

The fourth limit is that even if fiscal policy shifts AD, that may not solve the problem. The best case for fiscal policy is when a recession is caused by a decrease in aggregate demand. But sometimes the problem isn’t that people aren’t spending enough; the problem is that people don’t have enough to spend. In other words, some recessions are caused by real shocks of the type we analyzed in Chapter 32. As we will see, fiscal policy doesn’t work well at combating real shocks. Thus, in addition to the difficulty of shifting AD, we also have:

Real shocks: Shifting AD doesn’t help much to combat real shocks.

Let’s look at each of these limits in turn, noting that we are sticking with our basic scenario of an increase in government spending before we turn to the second type of expansionary fiscal policy, a decrease in taxes.

Crowding Out

Crowding out is the decrease in private spending that occurs when government increases spending.

When increased government spending comes at the expense of reduced private spending, we have the phenomenon of crowding out. Crowding out means that the initial shift in AD is less than the amount of the new government spending.

To consider an example, if the federal government builds a new interstate highway, that highway must be paid for. That means either higher taxes or more government borrowing (i.e., selling government bonds to the private sector). Both the taxes and the sale of bonds decrease aggregate demand, although perhaps with different timing. Let’s now consider those two financing scenarios in more detail, namely raising taxes and borrowing by selling more government bonds.

Raising Taxes to Finance Fiscal Policy The simplest case for understanding crowding out is when the new government spending is financed by an increase in taxes. That means the government spends more money, but of course, higher taxes mean that private individuals have less money to spend.

393

More concretely, let’s say that government increases taxes by $300 million, all of which it spends building a new highway. What would the private sector have done with that $300 million? Let’s assume that the private sector would have spent $270 million of the $300 million and simply held on to the other $30 million. Because the $270 million would have been spent by the private sector anyway, in this case the initial increase in short-run aggregate demand is only $30 million, or one-tenth of what was spent in gross terms on the new highway. So, if the private sector is spending, say, 90% of real income, fiscal policy won’t be very effective for stimulating aggregate demand. If government spends an extra dollar, 90 cents of that dollar would have been spent anyway. Only 10% of a given government expenditure will represent a net boost to aggregate demand.

At lower rates of private spending, more government spending does usually boost short-run aggregate demand. The government spends more money, whereas the private sector probably was not keen to have spent that entire amount right away. So fiscal policy will be most effective when people are otherwise afraid to spend their money. The latter scenario fits the story of the Great Depression that we discussed in Chapter 32 and also corresponds most closely to Figure 37.1 when the decrease in AD was caused by a decrease in  .

.

Selling More Bonds to Finance Fiscal Policy Rather than raising taxes today, the government often pays its bills with borrowed money. It’s like using a credit card: You don’t have to pay the bill today, but you do have to pay the bill sooner or later. Let’s look at what happens when the government borrows from the private sector to fund a spending increase.

Imagine that the government prints a bond and sells that bond to investors. The bond is an IOU, a promise to pay the investors in the future. The government sells the bond today and pockets the cash. With more cash in hand, the government can increase spending without increasing taxes. (Alternatively, the government could keep its own spending the same but cut taxes—we analyze this case later in the chapter.)

If government and consumers are spending more and taxes are the same, is there no crowding out? Not so fast. Remember that someone bought the bonds that the government sold. Where did the money to buy bonds come from?

In the simplest case, people bought more bonds instead of buying other financial assets. So, people buy more government bonds but fewer private bonds. If the private bonds were used to finance factories, then growth in investment,  , declines. This is another form of crowding out, and of course if crowding out is 100% of the initial change in fiscal policy, aggregate demand won’t shift out at all. The economy is simply substituting one form of spending for another form of spending.

, declines. This is another form of crowding out, and of course if crowding out is 100% of the initial change in fiscal policy, aggregate demand won’t shift out at all. The economy is simply substituting one form of spending for another form of spending.

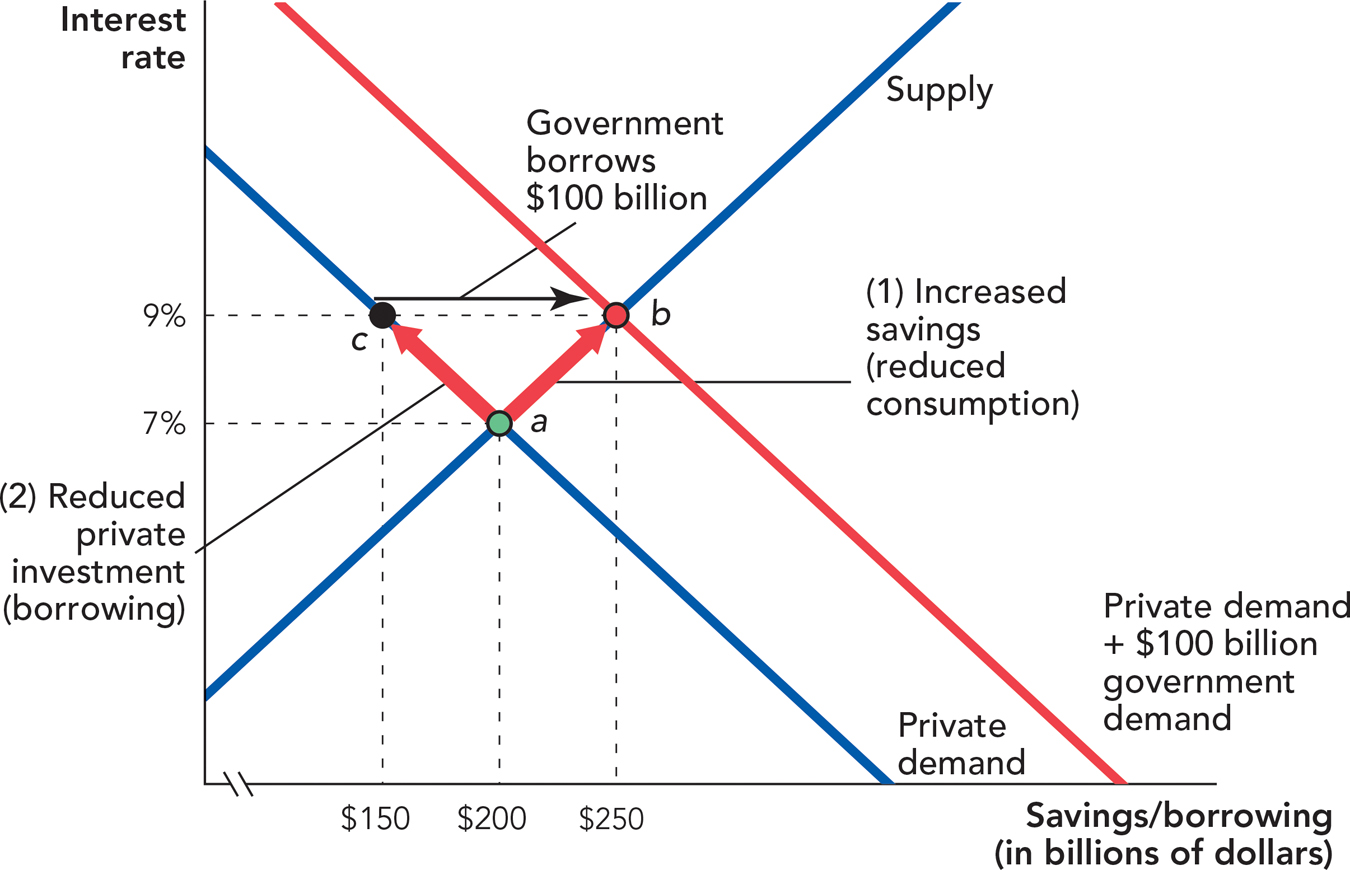

Remember also what happens to interest rates when the government sells bonds. Selling bonds pushes bond prices down, which pushes interest rates up. In other words, to sell more bonds, the government must offer a higher interest rate. A higher interest rate will encourage people to save more—you might think that is good but “saving more” is another way of saying “spending less.” Thus, when the government sells bonds and uses the proceeds to increase spending, some of the money comes from reduced private spending. So, there are two sources of crowding out in this case: Selling more bonds reduces private investment and also reduces private consumption, as shown in Figure 37.3.

394

Given the possibilities for crowding out, bond-financed expansionary fiscal policy is most likely to be effective when the private sector is, for some reason, reluctant to spend or invest. This is often the case in a depression or in times of great uncertainty or when people, for whatever reason, are simply holding onto their cash. In this case, the government investments do not displace comparable private investments, as the private investments would not have been forthcoming in any case. In addition, during a recession, investors often want to wait and see how uncertainty resolves before investing in private projects. In the meantime, investors may be happy to park their money in government bonds which are seen as safe even if they don’t pay a high interest rate—sometimes this is called a “flight to safety.” Thus, for both of these reasons, interest rates can fall during a recession and government borrowing may create less crowding out than would occur during a boom.

This point introduces a recurring theme of this chapter: The case for fiscal policy is strongest when the economy is in a recession caused by low aggregate demand.

Now let’s turn away from an increase in government spending and consider tax rebates and tax cuts, which are also designed to boost the flow of spending in the economy.

Tax Rebates and Tax Cuts as a Tool of Fiscal Policy Instead of government spending increases, tax rebates and tax cuts are another form of expansionary fiscal policy. In early 2008, for example, the economy weakened due to, among other factors, a slump in housing prices. The Bush administration tried to increase consumer spending by sending many taxpayers a check, called a tax rebate, for $300–$600, or about $78 billion in total.

If taxpayers spend the extra money from a rebate, aggregate demand shifts up and to the right, just as with increases in government spending. But taxpayers might also use their rebate to pay down debt. But if the government borrows money to fund a rebate and taxpayers turn around and use the same money to reduce their debt, there is no increase in spending at all!

395

In fact, something like this happened in 2008. Taxpayers used most of their rebate, about $62 billion of the $78 billion in total, to reduce their debt rather than to increase their spending. As a result, the net fiscal stimulus was not very large.

It makes sense for consumers to use tax rebates to pay off debt. Do you remember the idea of consumption smoothing from Chapter 29? As a rule, consumers want to avoid big ups and downs in consumption so when consumers are hit with a temporary negative shock like unemployment, they take on debt. When they are hit with a temporary positive shock, like an unexpected check from the government, they often pay down debt. As a result of consumption smoothing, a temporary tax rebate tends to create a small increase in spending over many years rather than a big increase in spending now; the latter, of course, is what the government wants to boost the economy.

If a temporary tax rebate doesn’t increase spending very much, what if politicians promise to make the rebate permanent? Yes, if consumers believe the rebate is permanent, they will spend more of it. But will consumers believe that a rebate is permanent when they can see that the government is borrowing a lot of money? The debt must be paid sometime, right? If consumers know that the government has a lot of debt and the government reduces taxes today, what do you think consumers will expect to happen to taxes tomorrow? We will return to this important question when we introduce the idea of Ricardian equivalence.

A tax rebate is different from a cut in marginal tax rates. A rebate means that taxpayers are handed a check—it’s just as if your Uncle Sam gives you some cash for your birthday. A rebate does not increase the incentive to invest or work. To increase the incentive to invest or work, the government must cut marginal tax rates, the additional tax that must be paid on additional earned income (see Chapter 36 for more on marginal tax rates). Cuts in tax rates as opposed to rebates have two expansionary effects, the spending effect and an additional incentive effect from the increased incentive to invest and work.

Consider a temporary investment tax credit. An investment tax credit gives businesses a tax cut or payment if they make an investment in, say, plant or machinery. The tax credit increases the incentive to invest but, more importantly, it increases the incentive to invest now, when times are tough. In other words, a temporary tax credit can accelerate investments that would have happened anyway (intertemporal substitution as we discussed in Chapter 33). In a similar way, a temporary reduction in the payroll tax or in the sales tax can encourage employers to hire more workers and consumers to spend more now—before the tax rises again—in this way increasing aggregate demand. If times are tough, this may be worthwhile.

A Special Case of Crowding Out: Ricardian Equivalence A tax cut opens the possibility of a special type of crowding out. If we hold government spending constant through time, then a tax cut today must be matched by a tax increase in the future. Now imagine that people are patient and very forward-looking. When the government cuts taxes today, these people realize that this means higher taxes in the future. These farsighted people will plan accordingly and save more today. Basically, they are saving more so that the future tax payments don’t cause them to give up familiar habits or move into old-age poverty; this “consumption smoothing” was explained in Chapter 29.

396

Ricardian equivalence occurs when people see that lower taxes today means higher taxes in the future, so instead of spending their tax cut, they save it to pay future taxes. When Ricardian equivalence holds, a tax cut doesn’t increase aggregate demand even in the short run.

If people save their tax cut instead of spending it, the aggregate demand curve does not shift to the right and there are no systematic macroeconomic effects. This scenario is sometimes called Ricardian equivalence, after the nineteenth-century British economist David Ricardo.

Most economists think it is unrealistic to stipulate that people understand their future tax burden and save accordingly to offset future tax burdens. Tyler knows that he doesn’t behave this way (and he’s a trained economist), but he does see some signs of this behavior from Alex. So Ricardian equivalence probably describes some people but not most people. In any case, to the extent that Ricardian equivalence reflects how people plan, bond-financed tax cuts are less effective in the short run than otherwise.

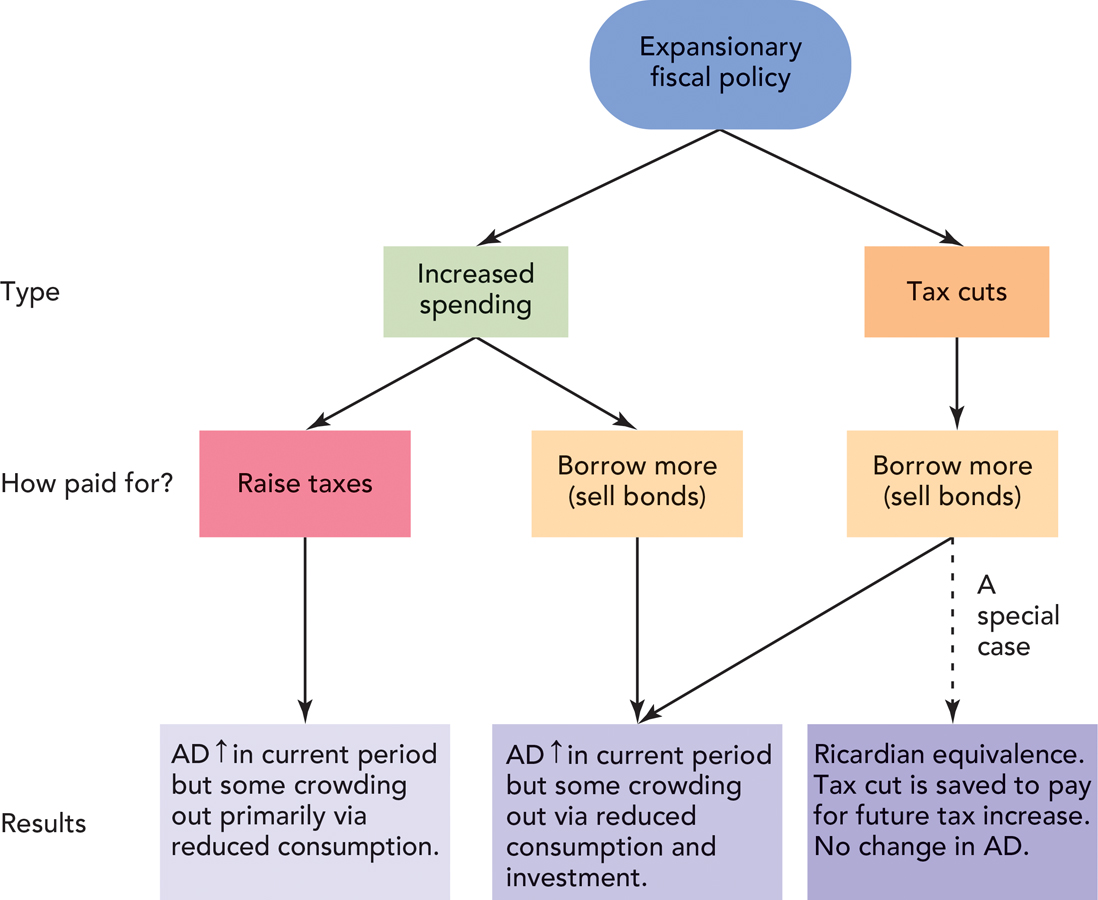

We’ve run through a few different cases. It is convenient to sum them up in the form of a diagram in Figure 37.4.

Figure 37.4 reminds us that expansionary fiscal policy can consist of either increased spending or tax cuts, and this policy can be paid for with either higher taxes or borrowing. Higher taxes reduce private spending, which means that some of the increased government spending has crowded out private spending. If the government borrows the money, some crowding out will still occur as private investment and private consumption fall. If Ricardian equivalence holds, then increased government borrowing to finance a tax cut will be matched by increased private saving and crowding out will be 100%.

397

A Drop in the Bucket: Can Government Spend Enough to Stimulate Aggregate Demand?

Surprisingly, one of the biggest problems with government spending as a boost to aggregate demand is simply that most changes in government spending are not very large in the short run. If changes to government spending are not large in the short run, the boost to aggregate demand won’t be very large either.

In the contemporary United States, changes in fiscal policy, in percentage terms, simply aren’t that large in a typical year. Most of the federal budget is determined well in advance and is remarkably stable. As we have seen in the previous chapter, among the largest budget categories are national defense, Social Security, Medicare, and interest on the debt. Those categories alone account for 65% of spending in a typical year and these programs are more or less on automatic pilot, with their yearly levels of spending set by automatic formulas or by previous agreements or commitments. Nonsecurity federal discretionary spending is less than 20% of the federal budget and most of this is not seriously up for grabs in any given year. Government spending, in today’s world, simply does not change very much in percentage terms on a year-to-year basis.

The fiscal stimulus plan passed under President Barack Obama in 2009 was the largest fiscal stimulus since military spending rose tremendously during World War II. Even this $800-$900 billion stimulus, however, was spread over 3–4 years so at its peak the stimulus was about 2% of annual GDP. These are large numbers relative to previous stimulus plans but, although significant, they are still modest compared to the total size of the economy. For this reason, many Keynesian economists suggested that the stimulus wasn’t large enough to succeed, but even if the Keynesians are right in principle, politically speaking, a larger stimulus bill probably was not possible. In September 2010, after most of the stimulus money was spent, unemployment remained at 9.6%.

A Matter of Timing

Bad timing provides another reason why fiscal policy is often not very effective, even in the short run. The United States Constitution stipulates that both Congress and the president must approve all expenditures. There are two houses of Congress, and of course legislation must pass through various committees. Sometimes an emergency stimulus occurs quickly, as in the 2008 case, which Congress passed a mere two weeks after President Bush requested it. But often the proposed fiscal projects are complicated and the budget cycle takes place over many months or sometimes even years; it can take a long time for new bills to be conceived, written, debated, and passed. Specific expenditures often must be coordinated with state and local governments, or the projects must produce environmental impact statements, or they must survive legal challenges. Even once the money is in place, it takes time to spend it; for instance, you can’t build a large airport or dam all at once and it doesn’t make sense to pay every contractor in advance.

In short, even a single government expenditure can take years to move from dream to reality. Yet fiscal policy is often intended to correct short-term problems in the business cycle. By the time the fiscal policy is in place, macroeconomic conditions often have changed entirely.

The list of relevant lags includes the following:

Recognition lag: The problem must be recognized.

Legislative lag: Congress must propose and pass a plan.

398

Implementation lag: Bureaucracies must implement the plan.

Effectiveness lag: The plan takes time to work.

Evaluation and adjustment lag: Did the plan work? Have conditions changed? (Return to lag 1!)

Tax cuts, the other major form of fiscal policy, also involve lags and uncertainties, at least with respect to their role in stimulating aggregate demand.

President George W Bush cut marginal tax rates in 2001, 2002, and 2003. The latter tax cuts came quite quickly after a recession loomed following 9/11 (in part because the tax cuts were mostly planned in advance for other reasons). But these tax cuts were not very effective as fiscal policy either. Each cut was less than 1% of national income, the economy was already recovering, plus most of the tax cuts went to relatively high-income groups, who tend to save their surplus funds. If we are thinking in terms of fiscal policy alone, tax cuts to the poor would probably result in more spending, except of course, that the poor don’t pay that much in taxes.

Monetary policy is also subject to lags, but these are generally shorter than for fiscal policy. Once the Federal Reserve recognizes a problem, it can act very quickly to implement changes to monetary policy. After 9/11, for example, the Federal Reserve stepped in the next day with massive infusions of cash to the banking system. The Federal Reserve can also evaluate and adjust its plan quickly as the economy responds or fails to respond. Fiscal policy, in contrast, is rarely adjusted in response to changes in economic conditions. The only place where fiscal policy might have an advantage over monetary policy is through the effectiveness lag. As we discussed in Chapter 34 and Chapter 35, the effectiveness of changes in monetary policy depends on matters like how willing banks are to lend and businesses are to borrow. A spending program, in contrast, typically has a direct impact on economic conditions, at least once the money is put into the economy.

Automatic stabilizers are changes in fiscal policy that stimulate AD in a recession without the need for explicit action by policymakers.

Automatic Stabilizers Some kinds of fiscal policy are built right into the tax and transfer system, and they do take effect without significant lags. These are called automatic stabilizers. Virtually all economists recognize the virtue of automatic stabilizers in keeping aggregate demand on a steady and regular course.

Fiscal policy automatically changes to keep private spending higher during bad economic times. For instance, when the economy is doing poorly, income, capital gains, and corporate profits are all down. As a result, most people and businesses will pay lower taxes and, given that the American tax system is progressive (see Chapter 36), possibly a lower tax rate as well. The lower tax burden makes aggregate demand more robust than it otherwise would be. The lower taxes don’t offset the curse of hard times (lowering your taxes by lowering your income is not the preferred way to go), but they soften the blow. Pretax incomes are perhaps falling, but post-tax incomes are not falling by as much.

Welfare and transfer programs also provide automatic stabilizers. When the economy is declining, increasing numbers of people apply for welfare, food stamps, unemployment insurance, and other programs designed to help low-income groups. These groups receive more income, and because of their precarious economic situation, they tend to spend that money fairly quickly. Spending on these categories helps people in tough times and also helps maintain aggregate demand.

Of course, it is not just fiscal policy that provides automatic stabilizers. When people save during good times and use their savings to tide them over in bad times (consumption smoothing, as discussed in Chapter 29), it’s an automatic stabilizer. Private market innovations, most of all credit, have also contributed to stabilization. Even though the 2008 credit crisis pared back some kinds of borrowing, it is still easier today to take out a second mortgage on one’s home than it was 30 years ago. If you need to send your kid to college, you can borrow more rather than cutting your spending ruthlessly. That way you can pay back the money over time, for a smoother adjustment. Credit cards, durable assets, the increased availability of used goods (eBay), and discount outlets—all allow the economy to weather hard times more easily than before.

399

Government Spending vs. Tax Cuts as Expansionary Fiscal Policy

Before turning to the last limit on fiscal policy, the fact that fiscal policy does not work well with real shocks, let’s briefly examine the differences between the two types of fiscal policy we have discussed, namely government spending and tax cuts. The differences between these types of fiscal policy are political and also economic. Let’s discuss the political differences first.

A tax cut or tax rebate puts more spending in the hands of the private sector, while an increase in government spending puts more spending in the hands of the government. People who are skeptical about government spending typically prefer fiscal policy to work through tax rebates and tax cuts rather than through changes in government spending.

Consider the infamous “Bridge to Nowhere,” a proposed bridge in Alaska that was to connect the town of Ketchikan (population 8,900) with its airport on the Island of Gravina (population 50) at a cost to federal taxpayers of $320 million. At present, a ferry service runs to the island, but some people in the town complain that it costs too much ($6 per car). If the town’s residents had to pay the $320 million cost of the bridge themselves—that’s $35,754 each!—do you think they would want the bridge? Of course not, so if the bridge is ever built, it may raise measured GDP but the costs will still exceed the benefits. That is a type of fiscal policy that we don’t want.

On the other hand, people who think that the U.S. government is not spending enough will tend to prefer that fiscal policy work through spending increases. The U.S. highway system is generally regarded as a highly productive investment of capital. If we can find equally productive public investments such as improvements to schools, science funding, and infrastructure (“bridges to somewhere”), then the case for public investment is strong, and if we can time these spending increases to help offset a recession, so much the better.

Do you recall our opening example? It’s a useful illustration of the political differences over fiscal policy. George Bush and Barack Obama both used expansionary fiscal policy to fight a recession but Bush, a Republican, focused on tax cuts, while Obama, a Democrat, served up a mix of tax cuts and government spending increases.

Fiscal Policy Does Not Work Well to Combat Real Shocks

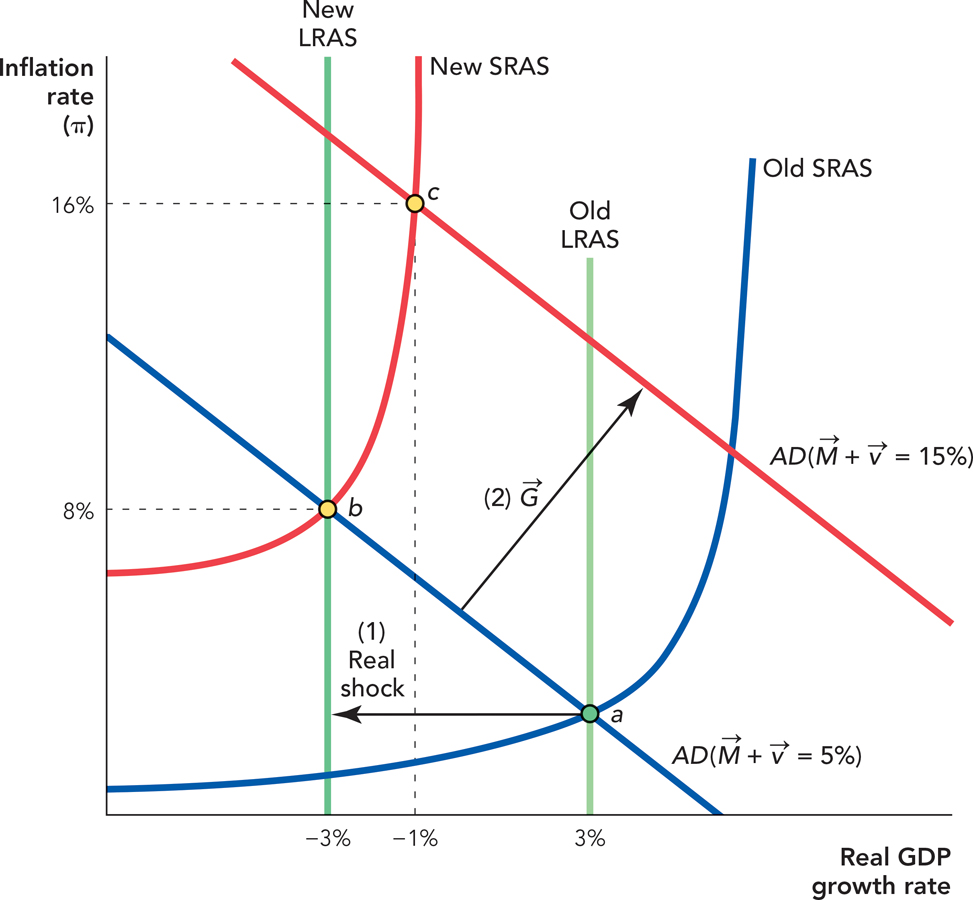

We have assumed so far that the problem fiscal policy needs to address is a deficiency in aggregate demand. But imagine, for example, that the recession is caused not by a fall in  , but by a real shock that reduces the productivity of capital and labor, shifting the long-run aggregate supply curve to the left. In Figure 37.5, for example, a real shock shifts the long-run aggregate supply curve to the left, moving the economy from point a to point b.

, but by a real shock that reduces the productivity of capital and labor, shifting the long-run aggregate supply curve to the left. In Figure 37.5, for example, a real shock shifts the long-run aggregate supply curve to the left, moving the economy from point a to point b.

(step 2), but due to the real shock, the economy is now less productive than before, and so the increase in aggregate demand shifts the economy to point c, where the growth rate is a little bit higher but the inflation rate is much higher.

(step 2), but due to the real shock, the economy is now less productive than before, and so the increase in aggregate demand shifts the economy to point c, where the growth rate is a little bit higher but the inflation rate is much higher.CHECK YOURSELF

Question 37.2

What happened to make the 2008 Bush tax rebate less powerful than anticipated?

What happened to make the 2008 Bush tax rebate less powerful than anticipated?

Question 37.3

Explain why a permanent cut in income tax rates can create a larger fiscal stimulus than a temporary cut.

Explain why a permanent cut in income tax rates can create a larger fiscal stimulus than a temporary cut.

Question 37.4

Keeping your answer to the previous question in mind, why does a permanent investment tax credit create a smaller fiscal stimulus than a temporary investment tax credit?

Keeping your answer to the previous question in mind, why does a permanent investment tax credit create a smaller fiscal stimulus than a temporary investment tax credit?

400

As before, the economy is in a recession at point b. Now suppose that government responds by increasing  . As usual, the aggregate demand curve shifts out, but now the economy is less productive than before, due to the real shock. As a result, an increase in

. As usual, the aggregate demand curve shifts out, but now the economy is less productive than before, due to the real shock. As a result, an increase in  will not move the economy back to point a. Instead, most of the increase in

will not move the economy back to point a. Instead, most of the increase in  will show up in inflation rather than in real growth, so the economy will shift from point b to point c with a much higher inflation rate and a slightly higher growth rate. As you may recall, the analysis is very similar to the analysis of monetary policy when facing a real shock.

will show up in inflation rather than in real growth, so the economy will shift from point b to point c with a much higher inflation rate and a slightly higher growth rate. As you may recall, the analysis is very similar to the analysis of monetary policy when facing a real shock.

In fact, the situation for fiscal policy is worse than Figure 37.5 indicates because when the problem an economy faces is a real shock, there is no inefficiency. Thus, unlike in Figure 37.1, the increase in  is unlikely to create much new growth and most of (perhaps even all of)

is unlikely to create much new growth and most of (perhaps even all of)  will crowd out other spending. (Another way of seeing this is to remember that the long-run aggregate supply curve shows the real rate of growth when the economy is operating at its full potential, and neither fiscal nor monetary policy can increase the growth rate above the Solow rate for very long.)

will crowd out other spending. (Another way of seeing this is to remember that the long-run aggregate supply curve shows the real rate of growth when the economy is operating at its full potential, and neither fiscal nor monetary policy can increase the growth rate above the Solow rate for very long.)

401

The economy is subject to both aggregate demand shocks and real shocks. Since some recessions are driven by real shocks, fiscal policy will not always be an effective method of combating a recession.