The Balance of Payments

The balance of payments is a yearly summary of all the economic transactions between residents of one country and residents of the rest of the world.

Let’s start with the international balance of payments. The balance of payments is a yearly summary of all the economic transactions between residents of one country and residents of the rest of the world. The balance of payments records sales of goods and services and also transfers of financial claims including stocks, bonds, loans, and ownership rights. We can also speak of the balance of payments with a specific country such as the balance of payments with China.

That sounds a little forbidding, but let’s go back to your trade deficit with the local supermarket. You spend money at the supermarket but earn money through your job. In the simplest case, when there is no borrowing or lending, a person’s trade deficits must be matched with other trade surpluses. In other words, if you want to spend, you must earn so your balance of payments does, in fact, balance (nets out to zero).

A country runs a capital surplus when the inflow of foreign capital is greater than the outflow of domestic capital to other nations.

Now let’s make this more realistic by adding borrowing and lending. Suppose you take out a student loan to pay for books, supplies, and housing. You have to pay back the loan someday, but in the meantime you are running a trade deficit. You are spending but you are not earning or “exporting” equivalent goods and services. In this case, your trade deficit is balanced with a loan, which we call a capital inflow or capital surplus. When we add up your trade deficit and the capital surplus, the balance of payments once again nets out to zero.

In the long run, unless you default on the loan, your trade deficit must disappear, and indeed it must turn into a trade surplus. That is, someday you will get a job and use your surplus earnings to pay back the bank loan. Paying back the loan limits your future consumption, that is, your ability to buy goods and services, but all things considered, your earlier borrowing was still a good idea, at least if you invested the money well.

We have seen that you can finance a trade deficit with a job or a loan. How else could you finance a trade deficit? If you had assets from previous transactions, you could sell the assets and spend the proceeds. If you owned some land, for example, you could sell the land, creating a capital surplus, which would offset your current deficit. Similarly, if you had reserves of cash from previous periods, you could draw on your reserves to finance a deficit. The more assets or cash that you had from previous transactions, the longer you could live the partying lifestyle by spending more than you were earning in the current period. Notice that when we add up the trade deficit, the capital inflow, and the changes in reserves, the balance of payments still balances.

We can write down these relationships as an identity, an equality that is always true:

If earnings are less than spending, then you are running a trade deficit. A trade deficit must be balanced by increases in debt (written as a negative number), sales of assets, or reductions in cash reserves. The reverse holds as well: If earnings are greater than spending, then a trade surplus must be balanced by reductions in debt, purchases of assets, or increases in cash reserves.

430

If you can understand that equation—and indeed you live it every day—you can understand the basic categories of international finance. The terms simply become a little more complicated once we move to the bigger level of a nation.

The international balance of payments presents a comparable expression:

Current account = (−)Capital account + Change in official reserves

Now let’s go through each term in detail.

The Current Account

The current account is the sum of the balance of trade, net income on capital held abroad, and net transfer payments.

The current account is the sum of three items:

The balance of trade (exports minus imports of goods and services)

Net income on capital held abroad, including interest and dividends

Net transfer payments, such as foreign aid

What unites the items in the current account is that they all measure transactions that are fully completed or closed out in a current period; they do not require any further transfer of funds in the future. To relate these categories back to the example of a single individual, category (1) is like earnings minus spending; category (2) is like earning money on a savings bond that your grandmother gave you when you were 10 (“interest income from abroad”); and category (3) is like getting money from relatives (“foreign aid”).

Now let’s apply these concepts to the United States. The U.S. current account will be higher and positive to the extent that, for instance, (1) America exports a lot of tractors, (2) American-owned beer factories in Canada pay high dividends to Americans, and (3) America receives foreign aid (this latter example is not usually the case). To consider the alternative, the current account balance will be lower and negative to the extent that, for instance, (1) America buys imported grapes from Chile, (2) German investments in Florida pay high dividends to Germans, and (3) America sends foreign aid to Afghanistan.

Categories 2 and 3 in a country’s current account tend to be stable over time. We can simplify by speaking as if the current account was just the balance of trade, exports minus imports. But keep in the back of your mind that terms 2 and 3 can be important for some countries. Foreign aid, for example, is important for smaller and poorer nations, when it can account for 10% or more of GDP. But when it comes to the United States, the balance of trade and the capital account are where we find most of the action.

The Capital Account, Sometimes Called the Financial Account

The capital account measures changes in foreign ownership of domestic assets including financial assets likes stocks and bonds as well as physical assets.

The capital account measures changes in foreign ownership of domestic assets including financial assets likes stocks and bonds as well as physical assets. When the Chinese government buys American government bonds or when Japanese investors buy assets like Rockefeller Center in Manhattan, the capital account of the United States increases. More generally, when there is more investment going into a country than out, that country is running a capital account surplus. When investment is leaving a country, that is called a capital account deficit; an example is when Zimbabwe residents send their money abroad rather than investing under their corrupt dictatorship. Less dramatically, many banks in New Zealand have been bought by Australian companies and that represents a shift of capital from Australia to New Zealand.

431

Notice how the capital account differs from “net income held on foreign assets abroad,” component 2 of the current account. When a Belgian buys a U.S. stock, the U.S. capital account increases (money flows into the United States). Three months later, when that same Belgian receives a dividend from the company, the U.S. current account decreases as “net income held on foreign assets abroad” is suddenly higher for Belgium. The capital account measures transactions like buying a stock that may result in future financial flows. The current account measures current financial flows.

The investments in the capital account are divided into the following categories:

Foreign direct investment (FDI)—When foreigners construct new business plants or set up other specific and tangible operations in the United States.

Portfolio investment— When foreigners buy U.S. stocks, bonds, and other asset claims. Unlike FDI, this switches the ownership of already existing investments and it does not immediately create new investment on net.

Other investment— This usually consists of movements of bank deposits. For instance, a wealthy French citizen might shift his or her bank account from Paris to New York.

The Official Reserves Account

This third category measures reserves or currency held by the government. This can include foreign currencies, gold reserves, and also International Monetary Fund (see later in the chapter) claims known as special drawing rights (SDRs), but for simplicity we will focus on foreign currencies. Sometimes governments stockpile U.S. dollars or other currencies such as the euro. Right now the Chinese government and central bank have stockpiled more than $1 trillion worth of U.S. dollars and dollar-denominated assets.

How the Pieces Fit Together

To understand the balance of payments in its totality, consider more concretely how this accounting identity stays in balance. Say that Walmart decides to buy more toys from China. Spending money on the toys increases the current a ccount deficit of the United States. Toy makers in China receive the money and must do something with it. If they take the money and use it to buy American tractors, the current account is back in balance. If they take the money and invest it back in the United States, say, by buying stocks, the American capital account surplus goes up by an equivalent amount. If they take the money and send it to a bank in New York, the capital account surplus goes up (this time in the “other investment” category). If they keep the money in a Chinese bank, there has been a change in reserves. No matter what they do with the money, the balance of payments will balance.

Two Sides, One Coin

Usually, the major changes in the balance of payments come through the current account and the capital account, rather than through changes in official reserves. So, a country that is running a current account deficit, such as the United States, balances its payments by running a capital account surplus. Similarly, a country, such as China, that is running a current account surplus, is usually also running a capital account deficit.

432

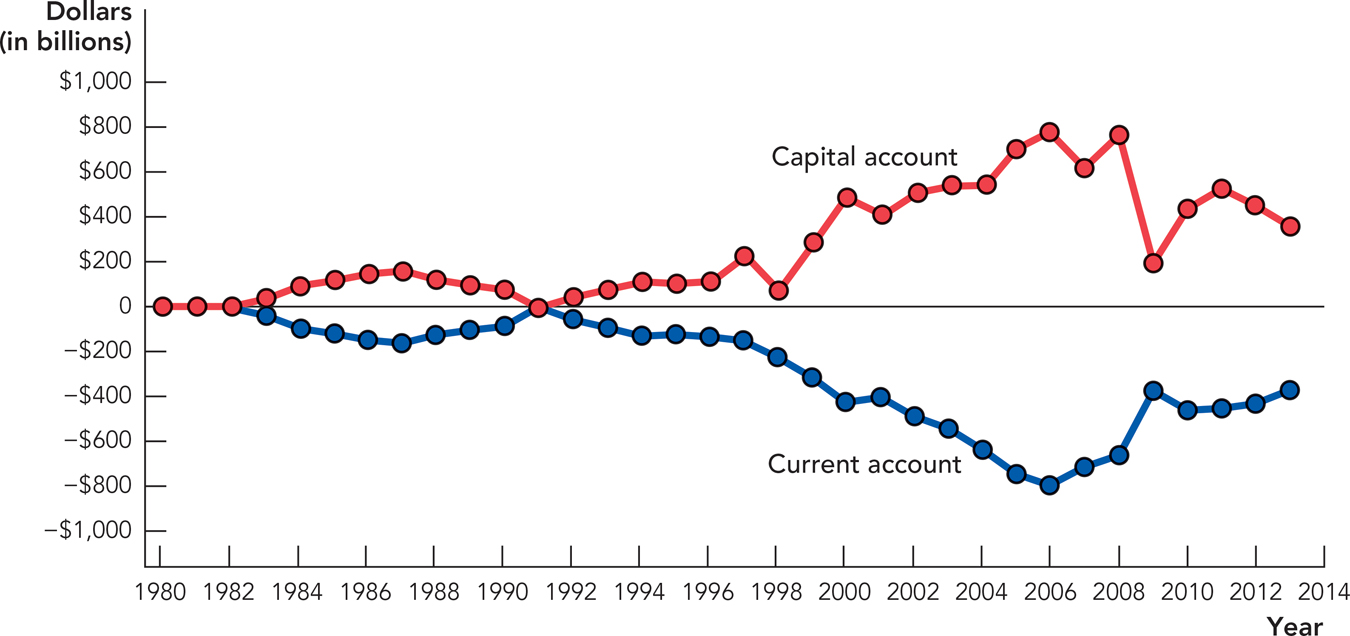

Figure 38.1 shows the U.S. balance of payments from 1980 to 2013. Notice that the two accounts are close to mirror images—when the current account is in deficit (negative), the capital account is in surplus (positive), and vice versa. (Differences are in fact almost entirely due to statistical discrepancies and the difficulty of identifying all financial transactions.)

The current account and capital account are two sides of the same coin. The media and politicians typically focus on the trade deficit, but it’s equally correct to look at the other side of the coin, the capital account surplus.

Now that we know that a trade deficit is typically balanced by a capital account surplus, let’s go back to our opening question and ask whether our trade deficit is a problem. First, note that this is the same thing as asking whether our capital account surplus is a problem. A surplus sounds better than a deficit so it is not surprising that many economists who think that trade deficits are not a problem focus on the flip side, the capital account surplus. We call the most optimistic view of those who focus on the capital account the “Great Place to Invest” view. We call the less optimistic view the “Foolishly Saving Too Little” view. Let’s start with optimism.

“The United States Is a Great Place to Invest” In this view, the trade deficit is driven by the fact that foreigners want to invest in the United States, the world’s wealthiest country and largest single, unified market. Instead of using dollars to buy U.S. cars, foreigners are using dollars to buy bonds and stocks and this inflow of investment is great for the United States. A capital account surplus will necessitate a current account deficit, but this is no problem. The investments in America will create more wealth and allow the United States to pay off future obligations without major problems. The fact that America is borrowing or selling assets is from this perspective like borrowing money or selling assets to pay for medical school—it isn’t a problem because the investment will pay off with a high-wage job. Advocates of this view sometimes speak of the rest of the world as having a “savings glut,” namely a lot of savings but no good place to put them, other than in the United States that is.

433

Not all economists who focus on the capital account are optimists, however. It’s also possible to look at the inflow of capital and ask why are American savings so low? We’ll call this the “Foolishly Saving Too Little” view

“Americans Are Foolishly Saving Too Little” In this view, the reason that capital is flowing into the United States is that Americans are consuming too much and not saving enough. Proponents of this view often tie the trade deficit with the government’s budget deficit. The U.S. government is spending more than it is taxing and the difference is being made up by borrowing from foreigners, creating a capital account surplus. In this view, a day of reckoning will come. Foreign investments in America represent a claim on American assets and someday the U.S. government will have to pay off those investment claims. This will lower American living standards and bring higher taxes, as well as the pain of significant economic adjustments. American borrowing from this perspective is like borrowing to buy a closet full of Manolo Blahnik shoes—fun while it lasts but not necessarily wise.

The Bottom Line on the Trade Deficit

The bottom line is this: Most economists think that the trade deficit per se is not a problem. As discussed in Chapter 2, trade is beneficial for the United States, and as previously shown, there is nothing peculiar about running a trade deficit—we all run trade deficits in some areas (e.g., with Whole Foods) and for some periods of time (e.g., when we finance education with a student loan). Countries, in this respect, are no different than individuals.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 38.1

An inhabitant of Lincoln, Nebraska, buys a German sports car for $30,000. What changes does this make to the U.S. current account?

An inhabitant of Lincoln, Nebraska, buys a German sports car for $30,000. What changes does this make to the U.S. current account?

Question 38.2

A German sports car manufacturer opens a new plant in South Carolina. How does this affect the U.S. current account and capital account?

A German sports car manufacturer opens a new plant in South Carolina. How does this affect the U.S. current account and capital account?

Question 38.3

Is there a link between a current account deficit and a capital account surplus?

Is there a link between a current account deficit and a capital account surplus?

The trade deficit, however, might indicate, or signal, a problem of low savings. If the United States has a problem with low savings, however, then it’s better to address the savings problem directly—in which case, the balance of trade will take care of itself—rather than blaming the Chinese or obsessing over the balance of trade numbers. Quotas, tariffs, and trade wars, for example, are unlikely to solve a savings problem. Indeed, if the United States is saving too little, then Americans are at least fortunate that they can borrow in international markets so that investment remains high even when U.S. savings rates are low.

To the extent that Americans are saving too little, there is a stronger case for reducing the government’s budget deficit by a combination of tax hikes and spending cuts. In the “Foolishly Saving Too Little” view, the United States is spending too much and the government could do its share to limit this problem by saving more, which means moving closer to a balanced budget or perhaps even running a surplus. We discussed the government budget deficit at greater length in Chapter 36.

Let us now turn to exchange rates. Working with the concepts in the balance of payments identity, we can see how supplies and demands will determine the relative values of different currencies.

434