What Are Exchange Rates?

An exchange rate is the price of one currency in another currency.

The most common means of payment in most (but not all!) foreign countries is a foreign currency and not the U.S. dollar. So, if you travel to a foreign country and you want to buy goods and services in that country, you will usually have to buy foreign currency with U.S. dollars. An exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of another currency.

Yahoo! finance prints a table like Table 38.1 every day. Table 38.1 gives exchange rates that held on September 8, 2010.

Table 38.1 Major Currency Exchange Rates

|

Currency |

U.S. $ |

¥en |

Euro |

Can $ |

U.K. £ |

Swiss Franc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 U.S. $ |

1 |

83.935 |

0.785 |

1.0391 |

0.6461 |

1.0133 |

|

1 ¥en |

0.0119 |

1 |

0.0094 |

0.0124 |

0.0077 |

0.0121 |

|

1 Euro |

1.2739 |

106.924 |

1 |

1.3237 |

0.8231 |

1.2908 |

|

1 Can $ |

0.9624 |

80.7766 |

0.7555 |

1 |

0.6218 |

0.9752 |

|

1 U.K. £ |

1.5477 |

129.9102 |

1.215 |

1.6083 |

1 |

1.5683 |

|

1 Swiss Franc |

0.9869 |

82.8333 |

0.7747 |

1.0255 |

0.6376 |

1 |

SEARCH ENGINE

For current information on exchange rates, search for the “Yahoo currency converter.”

We can read this table in either the vertical or horizontal direction. Read vertically, it tells us that the price of 1 yen is 0.0119 dollars, the price of 1 euro is 1.2739 dollars, the price of 1 Canadian dollar is 0.9624 U.S. dollars, and so forth. Read horizontally, it tells us that the price of 1 dollar is 83.935 yen, 0.785 euro, 1.0391 Canadian dollars, and so forth. Notice that there are always two ways of writing the price of a currency. We can say that 1 yen trades for 0.0119 dollars or that 1 dollar trades for 83.935 yen—this sometimes causes confusion so always make sure you know which rate is being quoted!

Exchange Rate Determination in the Short Run

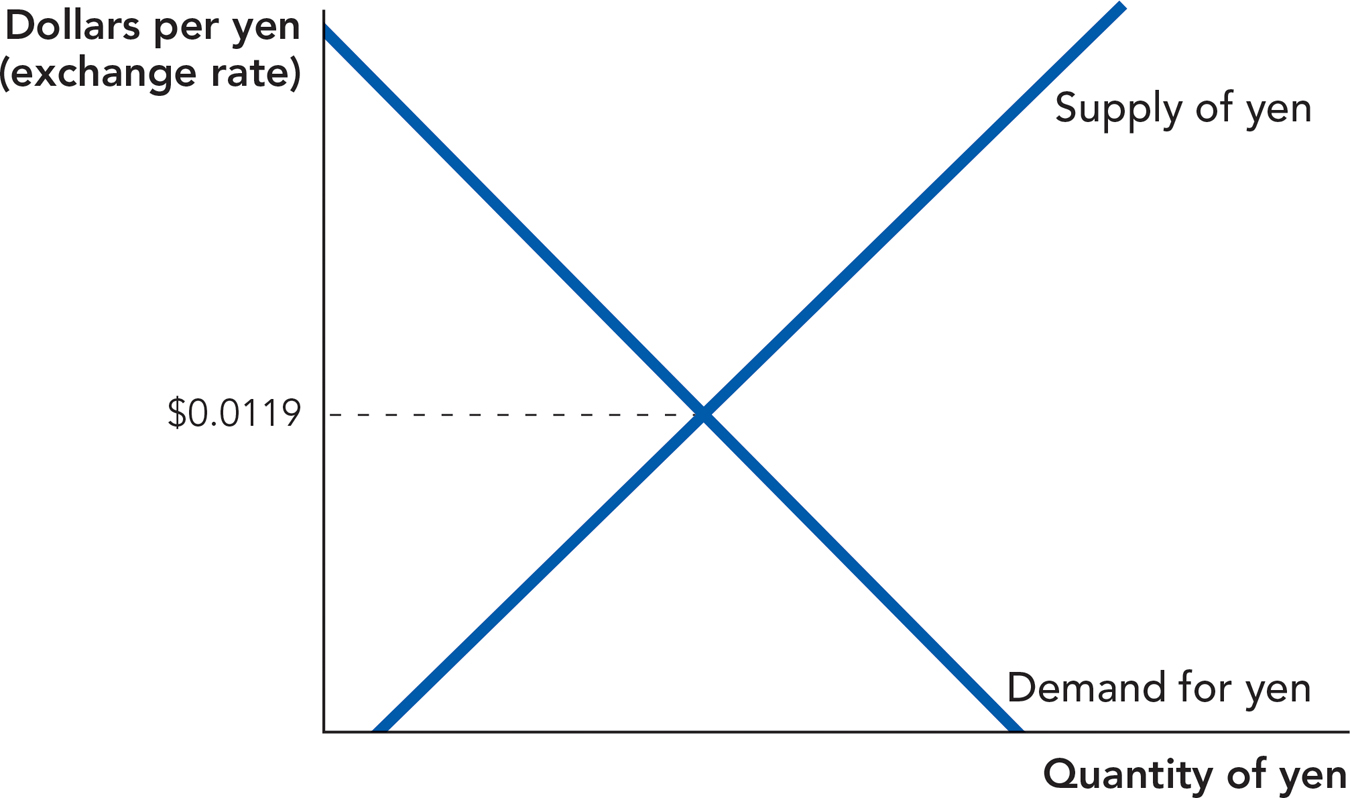

Exchange rates, like other market prices, are determined by supply and demand. For each currency, there is a price in every other currency. At any given moment, the exchange rate for a currency is determined by the intersection of the supply and demand for that currency. Figure 38.2, for example, shows the supply and demand for yen and the exchange rate in dollars per yen.

FIGURE 38.2

Notice that we have written “Dollars per yen” (“$/yen” in many books) on the vertical axis. This is the price of 1 yen in dollars. If this price goes up—that is, we move up along the vertical axis—it means that the Japanese yen is stronger, namely it takes more dollars to buy 1 yen. If this price goes down, the Japanese yen is weaker.

In this chapter when we are analyzing the supply and demand for yen, we will always put the price of yen, “Dollars per yen” on the vertical axis. But if we analyze the supply and demand for dollars, we will put the price of dollars in, say, euros per dollar on the vertical axis.*

Let’s now look at some factors that can shift the demand and supply curves.

Changes in Demand for a Currency The first principle is simple:

An increase (decrease) in the demand for a country’s exports tends to increase (decrease) the value of its currency.

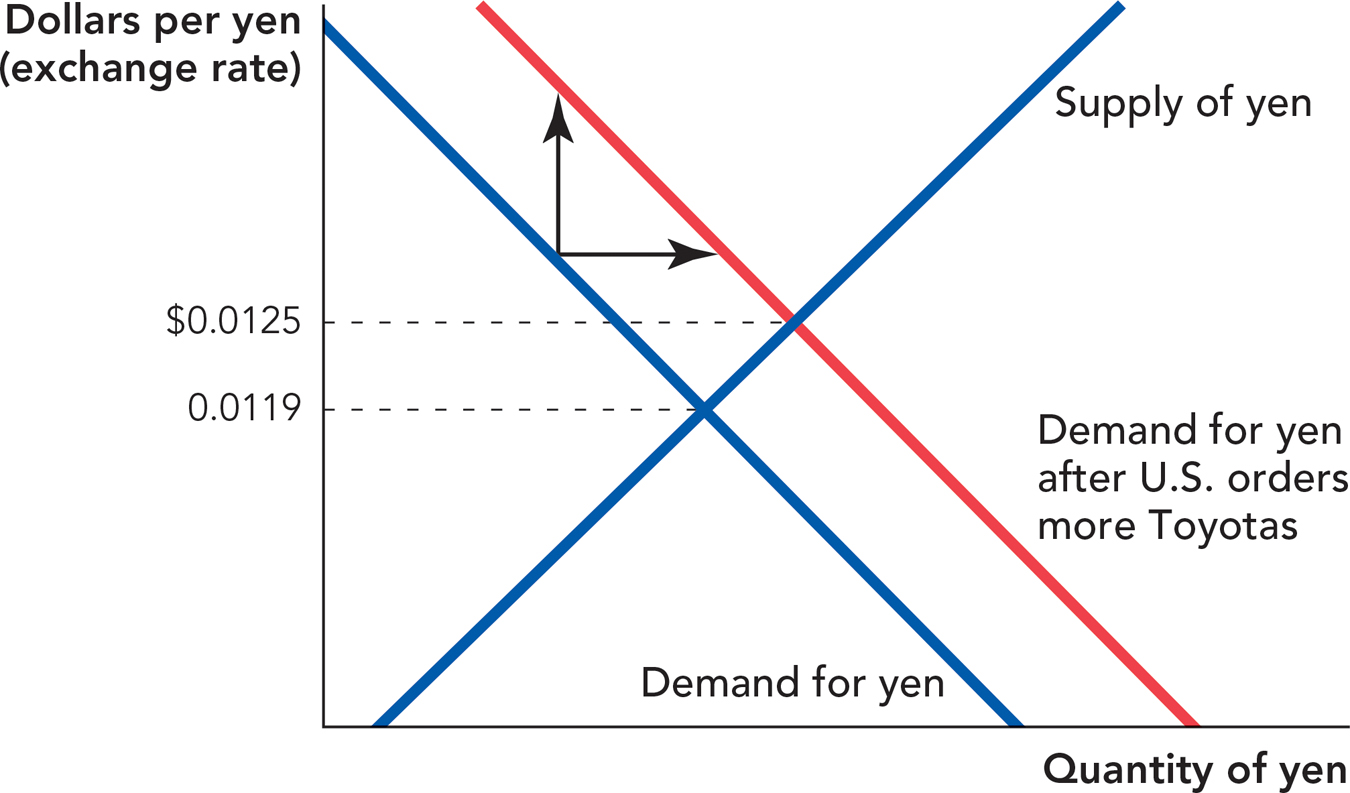

When Japanese cars become popular around the world, this strengthens the value of the yen. For instance, when U.S. car dealerships order more Toyotas from Japan, they must (ultimately) pay for the cars in yen. An increase in the demand for Japanese goods, therefore, shifts the demand curve for yen up and to the right, illustrated in Figure 38.3.

FIGURE 38.3

An appreciation is an increase in the price of one currency in terms of another currency.

As usual, an increase in demand increases the price. In this case, the price of one yen increases from 0.0119 dollars to 0.0125 dollars. An increase in the price of a currency is also called an appreciation.

Increasing exports are not the only way a currency can change in value. We also have a second principle:

The more desirable (undesirable) a country is for foreign investment, the higher (lower) the value of that nation’s currency.

Ever since the signing of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) and the evolution of real democracy in Mexico, American investors have been keener to invest in that country. To invest in Mexico, an American business must convert dollars into pesos, thereby shifting the demand curve for pesos to the right and raising the value of the peso. In this context, note that a “stronger peso” means a “weaker dollar,” or whatever other currency we are considering.

Alternatively, many governments of sub-Saharan Africa have failed to secure the property rights of foreign investors. The demand to invest is correspondingly weak, shifting the demand curve for these countries’ currencies to the left and lowering the value of these currencies.

High interest rates, all other factors held equal, is another factor that attracts investment, increasing the demand for and thus the value of a currency. For instance, if New Zealand “Kiwi bonds” are yielding 9%, and U.S. Treasury securities of comparable maturity are yielding 4%, this favors the strength of the New Zealand currency. (The New Zealand currency is also called the dollar; investors sometimes say “the Kiwi dollar” to avoid confusion with the U.S. dollar.) Investors will be more inclined to hold New Zealand securities, and of course to do so, they must use the New Zealand currency, thereby shifting out demand.

There is yet another cause of stronger demand for a currency:

An increase in the demand to hold dollar reserves boosts the value of the dollar on international markets.

Many governments and central banks hold dollars as a “reserve currency.” This means simply that dollars are a preferred means of saving and enjoying liquidity. Of all the currencies held in the world for these official reserves purposes, American dollars comprise two-thirds of the total.

The U.S. dollar is truly a global currency. If a Brazilian company buys a turbine engine from Turkey, it is probably billed in dollars and probably pays in dollars, not the currency of either Turkey or Brazil. If Colombian drug dealers bury some money in their backyard, it is probably dollars. When these demands for dollars rise, the dollar becomes more valuable. Again, the demand curve for dollars will shift to the right. However, if the Colombian government ever succeeds in stopping the drug trade, the demand for U.S. dollars would fall and the demand curve for dollars would shift back to the left.

The Swiss franc, by the way, is another global reserve currency. Even though Switzerland is a small country, it has a long tradition of peace and stability, and to some extent bank secrecy. The Swiss franc is viewed as a “safe haven” currency, even when the rest of the world is experiencing trouble. This is one reason why the Swiss franc tends to be relatively strong. Furthermore, the proverbial “bad guys” used to have secret Swiss bank accounts (since 9/11 and the growth of financial investigations, they’re not so secret any more) and to invest some of their money in Swiss francs; that is one reason why so many James Bond movies have scenes there, and of course because the Alps are pretty on the big screen.

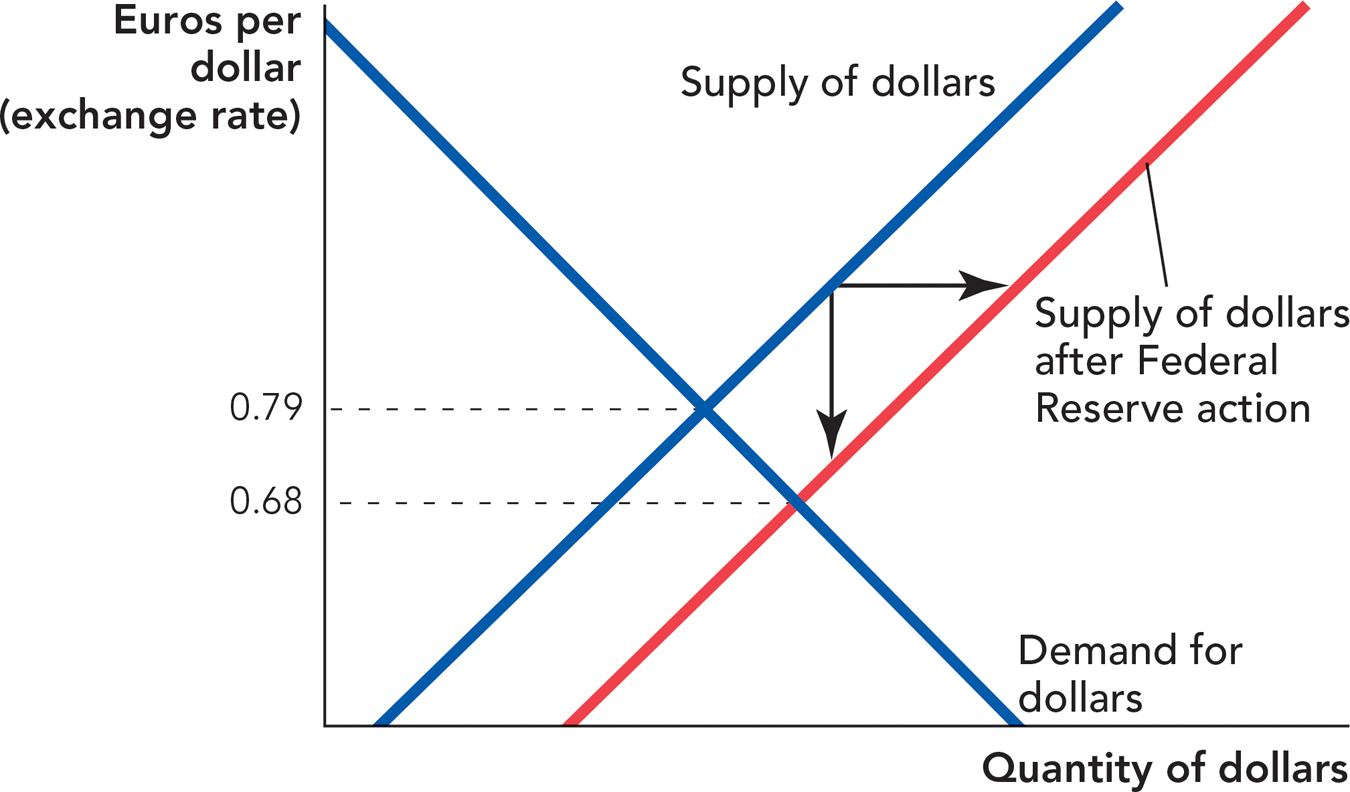

A depreciation is a decrease in the price of a currency in terms of another currency.

Changes in the Supply of a Currency An increase in the supply of a currency causes the currency to lose some of its value, that is, fall in price. A fall in the price of a currency is also called a depreciation. Figure 38.4 shows the effects of an increase in supply, a shift of the supply curve down and to the right.

FIGURE 38.4

If the Federal Reserve increases the supply of U.S. money, this will reduce the value of the dollar relative to other currencies. The not-so-surprising result, as shown in Figure 38.4, is a lower value for the U.S. dollar on world markets.

You may recall from Chapter 31 that the government in Zimbabwe has been printing trillions of Zimbabwe dollars, causing a large increase in the Zimbabwean inflation rate. At the beginning of 2002, for example, one Zimbabwe dollar was worth about 0.018 of a U.S. dollar or just under 2 cents. With the massive increase in the supply of Zimbabwean dollars, the value of the Zimbabwean dollar fell, so that by 2006 1 Zimbabwe dollar was worth less than 0.00001 of a U.S. dollar or about one-thousandth of a U.S. penny.

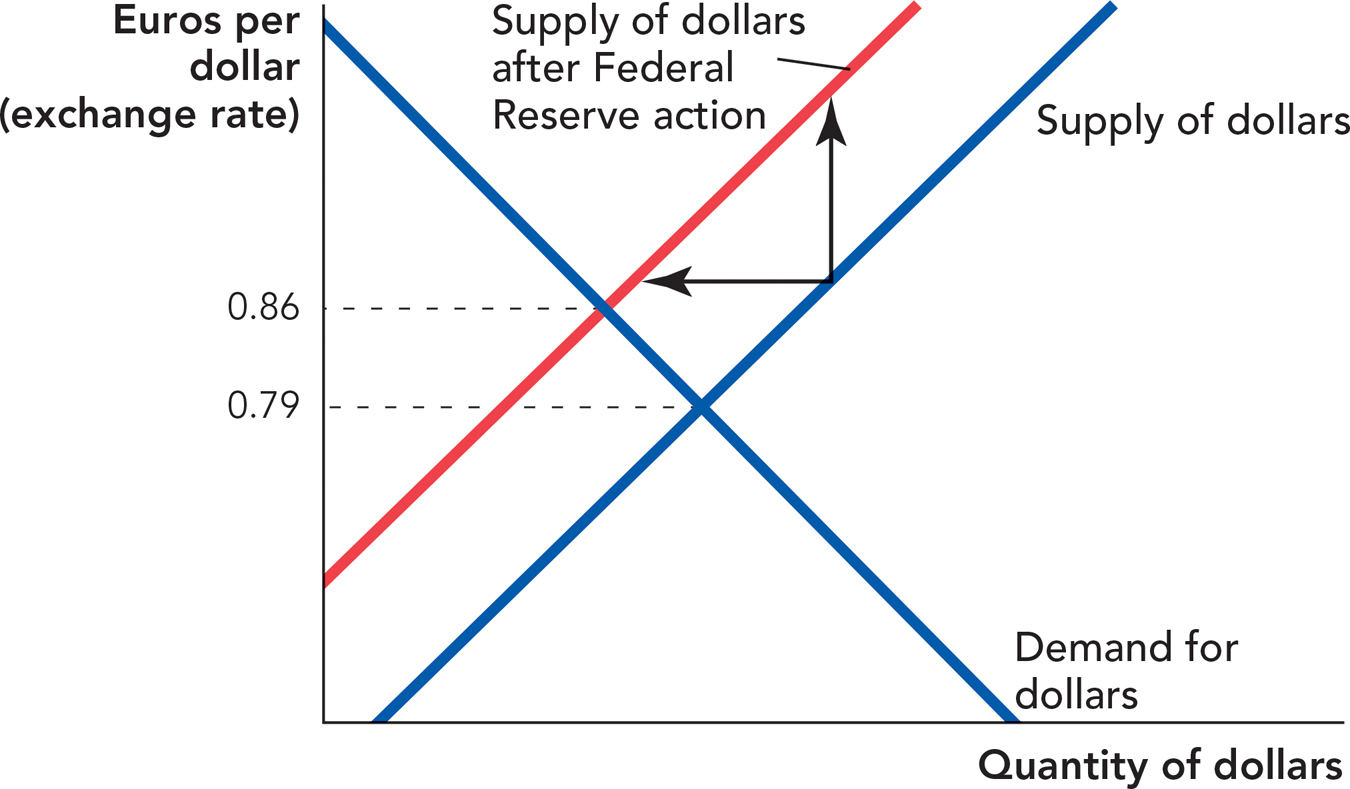

A tighter monetary policy, which means a decrease (or slower increase) in the supply of a currency, would shift the supply curve up and to the left and raise the value of the dollar as we show in Figure 38.5.

FIGURE 38.5

Exchange Rate Determination in the Long Run

These changes play themselves out in foreign exchange markets every day. But a full explanation outlines why the supply and demand curves lie where they do in the first place, and not just what happens when they shift.

To see the broader picture, consider that the value of a currency is derived, ultimately, from the value of what it can purchase. Money buys or is a potential claim on goods, services, and investments. Given this fact, equilibrium requires that the return to spending a dollar in Chicago, Berlin, or Tokyo—whether on goods, services, or investments—all yield the same expected return.

Before we can explain this point fully and use it to give a more exact account of exchange rates, we must first outline the difference between real and nominal exchange rates.

We are already familiar with the distinction between real and nominal variables from earlier chapters. To recap, in a domestic setting how much a dollar is worth depends on the level of prices for goods and services. We now extend this same comparison to Cairo, Berlin, and Tokyo. How much a dollar is worth in Tokyo depends on two things: the exchange rate between the dollar and the Japanese Yen, and the level of prices for goods and services in Japan, measured in Japanese Yen.

On September 8, 2010, 1 dollar would buy 83.935 yen. At first glance, it might appear that the Japanese yen is a very weak currency. Why should one dollar buy so many yen, if not for the weakness of the yen? But it is wrong to think that the stated rate of exchange reflects the relative weakness of the yen.

The nominal exchange rate is the rate at which you can exchange one currency for another.

If 1 dollar buys 83.935 yen, we know only the nominal exchange rate, which is simply the rate at which you can exchange one currency for another; this is the rate you find quoted in the newspaper or on Yahoo!, as previously described.

The real exchange rate is the rate at which you can exchange the goods and services of one country for the goods and services of another.

The real exchange rate is the rate at which you can exchange the goods and services of one country for the goods and services of another. To calculate the real exchange rate between the United States and Japan, for example, you need to know the nominal exchange rate plus the price of a similar basket of goods in both the United States and Japan. Notice that an exchange rate of 1 dollar to 80 yen means very different things, depending whether an order of sushi costs 1 yen, 1 million yen, or about 240 yen (the true price, roughly). If an order of sushi costs 3 dollars in the United States and 240 yen in Japan, then the real exchange rate is about 1:1.

The purchasing power parity (PPP) theorem says that the real purchasing power of a money should be the same, whether it is spent at home or converted into another currency and spent abroad.

The Purchasing Power Parity Theorem The purchasing power parity (PPP) theorem is:

The real purchasing power of a money should be about the same, whether it is spent at home or converted into another currency and spent abroad.

Put in other words, the quantity of goods and services that can be obtained for a given currency should be about the same everywhere, adjusting for the costs of trading those goods and services. The core idea is that spending your dollars in Chicago, or converting them into yen and spending them in Tokyo (which might include buying Japanese goods and shipping them back home for resale), should yield about the same benefits.

More concretely, the PPP theorem makes two predictions. First, Toyotas in Japan should cost about as much as Toyotas in California; the same should be true for other individual goods. Second, the cost of a general bundle of goods and services should be about the same everywhere.

The law of one price says that if trade were free, then identical goods should sell for about the same price throughout the world.

Purchasing power parity is an application of the law of one price, the principle that if trade were free, then identical goods should sell for about the same price throughout the world. If Toyotas were cheaper in Tokyo, it would make sense to buy Toyotas in Japan and ship them to the United States. Conversely, if Toyotas are cheaper in the United States, they will be shipped to Japan. Of course, shipping cars from one country to another is not the only way to gain from a difference across prices. Toyota might set up a new auto plant in Tennessee rather than in Tokyo or Osaka, thereby shifting supply into the North American market.

That example is only for cars but the principle can be extended to a broader set of possible transactions. The return to spending a dollar (or yen, or euro, etc.) at home or abroad must be roughly equal, and exchange rates and prices will adjust to equalize those returns. Those adjustments will determine the real exchange rate between any two currencies.

Recall from Chapter 31 that in the long run, money is neutral. We used that principle to explain why in the long run the money supply does not influence real GDP, real interest rates, or real prices. Exactly the same principle applies here, except that now we apply the principle to two monies! Since money is neutral in the United States and money is neutral in Japan, neither the supply of dollars nor the supply of yen can change the real exchange rate in the long run. In other words, governments or central banks set nominal exchange rates, but market forces set the real exchange rate. As usual, however, this applies only in the long run. In the short run, as we will discuss further later in the chapter, the government can influence the real exchange rate and this will be important for macroeconomic policy.

The Purchasing Power Parity Theorem Is Only Approximately True Purchasing power parity is limited by the costs of trading, transacting, and shuffling resources. That is one reason why purchasing power parity holds only approximately. At least three constraints on trade prevent prices from being fully equalized across borders:

Transportation costs. The price of cement might be much higher in Japan than in California, but it still will not be profitable to put cement on a boat and ship it from California to Japan. Cement is very heavy and the shipping would cost a great deal. Purchasing power parity applies only to the extent that goods can be transported easily. Notice also that many personal services—haircuts are the classic example—cannot easily be shipped, although sometimes the labor behind those services can migrate from one country to another. Thus, purchasing power parity is more likely to hold for goods that are cheap to ship, like iPhones, than for cement or haircuts.

Some goods cannot be shipped at all. Sipping a coffee in Paris is different from going to a Starbucks in suburban Ohio, even if the coffee is the same. The coffee can be transported cheaply but Paris cannot be shipped.

Similarly, an apartment in London, Canada, costs less than a similar-sized apartment in London, England. Canada cannot easily cut off its land and ship it to England so prices of apartments will not equalize. More generally, the price of land and any good that uses a lot of land in its production will not equalize across countries.

Tariffs and quotas. To the extent that governments tax or otherwise restrict trade, prices will not equalize across countries. Tariffs or quotas will hinder market exchange and thus the arbitrage of differing prices.

These restrictions show that purchasing power parity will hold approximately—rather than strictly—for a broad basket of goods and services. In other words, living in London, England, will remain more expensive than living in London, Canada.

Deviations from purchasing power parity are often large and long-lasting for services. Goods are easy to transport and so tend to equalize in price more than services, which are difficult to transport. Services, therefore, are cheaper in poorer countries because immigration laws limit the extent to which labor can move from poor countries to rich countries. Wages on the American side of the border are much higher than wages on the Mexican side of the border. The result is that a haircut is much cheaper in Mexico than in the United States. One of the thriftier authors of this textbook often gets his hair cut during trips to Mexico for this reason! Servants are also much cheaper in poorer countries. Even a middle-class family in Mexico, India, or Thailand will often employ many servants. The services of a physician, even a high-quality Western-trained physician, are also cheaper in poorer countries; that explains why many people are going to India for plastic surgery or hip replacements—plus you can see the Taj Mahal after your surgery is over. Computers, copper, automobiles, and other goods that can be easily shipped are not systematically cheaper in poorer countries.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 38.4

If the U.S. dollar is a safe haven currency and risk increases, what does this do to the value of the dollar: send it higher or lower?

If the U.S. dollar is a safe haven currency and risk increases, what does this do to the value of the dollar: send it higher or lower?

Question 38.5

If the Federal Reserve increases the U.S. money supply, what will this do to the value of the dollar compared to the euro?

If the Federal Reserve increases the U.S. money supply, what will this do to the value of the dollar compared to the euro?

Question 38.6

If purchasing power parity holds and the nominal exchange rate is 1 pound for 2 dollars, how much should a Big Mac cost in London if a Big Mac costs $4.00 in New York?

If purchasing power parity holds and the nominal exchange rate is 1 pound for 2 dollars, how much should a Big Mac cost in London if a Big Mac costs $4.00 in New York?

Question 38.7

How does a tariff affect purchasing power parity?

How does a tariff affect purchasing power parity?

How close the real world fits purchasing power parity depends on the nations involved and their ease of trading. As trading costs fall, purchasing power parity is more likely to hold closely. As trading costs rise, the bounds become looser. Purchasing power parity holds more exactly true between the United States and Canada—similar and adjacent countries—than between Japan and Mexico. Note that the concept of “tradeable” is a matter of degree, not an absolute, so how much purchasing power parity holds is a matter of degree as well.

Purchasing power parity also holds more tightly in the long run than in the short run. In the short run, trading costs might hinder entrepreneurs from erasing differences in prices. In the long run, it is more likely that entrepreneurs will find a way to bring prices closer together across international borders.

When it comes to the short run, and within the boundaries set by purchasing power parity, economists still debate the causes of daily exchange rate movements. About $4 trillion in foreign exchange transactions take place in a typical day. Most of those trades are speculative, done to earn a profit by trying to outguess the market. The short-run froth of daily price movements is set largely by psychology and expectations. Traders are guessing where the market is headed, as shaped by supply and demand, but some of the short-run trading is just guessing at the short-run behavior of other traders. Sometimes the small, short-run movements in exchange rates are called “noise,” which is the economist’s polite way of saying we don’t understand what causes them or what they mean.