What Shifts the Demand Curve?

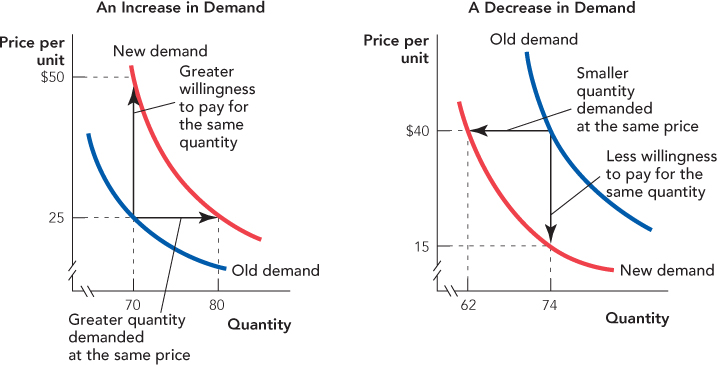

The demand curve for oil tells us the quantity of oil that people are willing to buy at a given price. Assume, for example, that at a price of $25 per barrel, the world demand for oil is 70 million barrels per day. An increase in demand means that at a price of $25, the quantity demanded increases to, say, 80 million barrels per day. Or, equivalently, it means that the maximum willingness to pay for 70 million barrels increases to say $50 per barrel. The left panel of Figure 3.5 shows an increase in demand. An increase in demand shifts the demand curve outward, up and to the right.

The right panel of Figure 3.5 shows a decrease in demand. A decrease in demand shifts the demand curve inward, down and to the left.

FIGURE 3.5

What kinds of things will increase or decrease demand? Unfortunately for economics students, a lot of things! Here is a list of some important demand shifters:

Important Demand Shifters

Income

Income

Population

Population

Price of substitutes

Price of substitutes

Price of complements

Price of complements

Expectations

Expectations

Tastes

Tastes

If you must, memorize the list. But keep in mind the question, “What would make people willing to buy a greater quantity at the same price?” Or equivalently, “What would make people willing to pay more for the same quantity?” With these questions in mind, you should always be able to come up with a fairly good list on your own.

Here are some examples of demand shifters in action.

Income When people get richer, they buy more stuff. In the United States, people buy bigger cars when their income increases and big cars increase the demand for oil. When income increases in China or India, many people buy their first car and that too increases the demand for oil. Thus, an increase in income will increase the demand for oil exactly as shown in the left panel of Figure 3.5.

A normal good is a good for which demand increases when income increases.

When an increase in income increases the demand for a good, we say the good is a normal good. Most goods are normal; for example, cars, electronics, and restaurant meals are normal goods. Can you think of some goods for which an increase in income will decrease the demand? When we were young economics students, we didn’t have a lot of money to go to expensive restaurants. For 50 cents and some boiling water, however, we could get a nice bowl of instant Ramen noodles. Ah, good times. When our income increased, however, our demand for Ramen noodles decreased—we don’t buy Ramen noodles anymore! A good like Ramen noodles for which an increase in income decreases the demand is called an inferior good. What goods are you consuming now that you probably wouldn’t consume if you were rich? Economic growth is rapidly increasing the incomes of millions of poor people in China and India. What goods do poor people consume in these countries today that they will consume less of 20 years from now?

An inferior good is a good for which demand decreases when income increases.

Population More people, more demand. That’s simple enough. Things get more interesting when some subpopulations increase more than others. The United States, for example, is aging. Today the 65-year-old and older crowd makes up about 13 percent of the population. By 2030, 19.4 percent of the population will be 65 years or older. In fact, demographers estimate that by 2030, 18.2 million people in the United States will be over 85 years of age!1 What sorts of goods and services will increase in demand with this increase in population? Which will decrease in demand? Entrepreneurs want to know the answers to these questions because big profits will flow to those who can anticipate new and expanded markets.

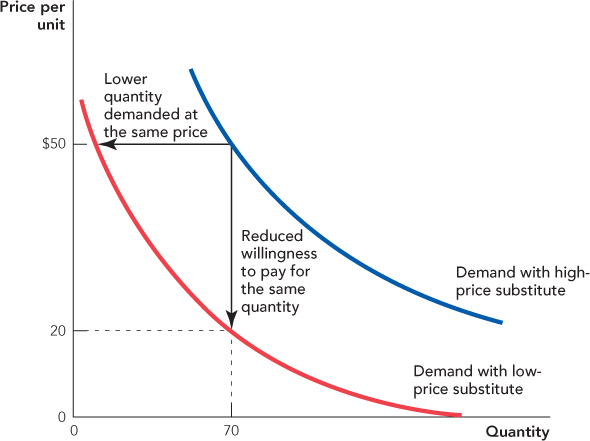

Price of Substitutes Natural gas is a substitute for oil in some uses such as heating. Suppose that the price of natural gas goes down. What will happen to the quantity of oil demanded? When the price of natural gas goes down, some people will switch from oil furnaces to natural gas, so the quantity of oil deman ded will decrease—the demand curve shifts down and to the left. Figure 3.6 illustrates.

FIGURE 3.6

If two goods are substitutes, a decrease in the price of one good leads to a decrease in demand for the other good.

More generally, a decrease in the price of a substitute will decrease demand for the other good. A decrease in the price of Pepsi, for example, will decrease the demand for Coca-Cola. A decrease in the price of rental apartments will reduce the demand for condominiums. Naturally, an increase in the price of a substitute will increase demand for the other substituted good.

If two goods are complements, a decrease in the price of one good leads to an increase in the demand for the other good.

Price of Complements Complements are things that go well together: French fries and ketchup, sugar and tea, iPhones and iPhone apps. More technically, good A is a complement to good B if greater consumption of A encourages greater consumption of B. Ground beef and hamburger buns are complements. Suppose the price of beef goes down. What happens to the demand for hamburger buns? If the price of beef goes down, people buy more ground beef and they also increase their demand for hamburger buns; that is, the demand curve for hamburger buns shifts up and to the right. A supermarket having a sale on ground beef, for example, will also want to stock up on hamburger buns.

A decrease in the price of a complement increases the demand for the complementary good. An increase in the price of a complement decreases the demand for the complementary good. It sounds complicated, so just remember that ground beef and hamburger buns are complements and you should be able to work out the relationship.

Expectations In July 2007, a construction worker in the oil fields of southern Nigeria was kidnapped. On hearing the news, oil prices around the world jumped to record high levels.2 Was a single construction worker so critical to the world supply of oil? No. What spooked the world’s oil markets was the fear that the kidnapping was the beginning of large-scale disruption in the Niger Delta, Nigeria’s main oil-producing region and the base for many antigovernment rebels. Fear of future disruptions increased the demand for oil as businesses and governments worked to increase their emergency stockpiles. In other words, the expectation of a reduction in the future oil supply increased the demand for oil today.

You have probably responded to expectations about future events in a similar way. When the weather forecaster predicts a big storm, many people rush to the stores to stock up on storm supplies. In the week before Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, for example, sales of flashlights increased by 700 percent and battery sales increased by 250 percent compared with the week before.3

Expectations are powerful—they can be as powerful in affecting demand (and supply) as events themselves.

Tastes In the 1990s, doctors warned that too much fat could lead to heart attacks and demand for beef decreased. The 2001 publication of Dr. Atkins’ New Diet Revolution, a book promising weight loss on a high-protein, low-carb diet, increased the demand for beef. Steakhouses like Outback Steakhouse and the Brazilian-inspired Fogo De Chão started to appear everywhere.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 3.1

Economic growth in India is raising the income of Indian workers. What do you predict will happen to the demand for automobiles? What about the demand for charcoal bricks for home heating?

Economic growth in India is raising the income of Indian workers. What do you predict will happen to the demand for automobiles? What about the demand for charcoal bricks for home heating?

Question 3.2

As the price of oil rises, what do you predict will happen to the demand for mopeds?

As the price of oil rises, what do you predict will happen to the demand for mopeds?

Shaun White’s multiple golds in the Winter X games and his Olympic gold medals in the snowboard halfpipe have helped him to sell millions of copies of his video game, Shaun White Snowboarding, not to mention lots of Burton Snowboards, Oakley eyewear, and Red Bull energy drinks. Changes in tastes caused by fads, fashions, and advertising can all increase or decrease demand.

Can tastes change something like the demand for oil? Sure. The environmental movement has made people more aware of global climate change and how the consumption of oil adds carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. As a result, the demand for hybrid cars has increased, more people are recycling things like plastic bags, and nuclear power is once again being discussed as an alternative source of energy. All of these changes can be understood as a change in tastes or preferences.

The bottom line is that while many factors can shape market demand, most of these factors should make intuitive sense. After all, you are, on a daily basis, part of market demand.