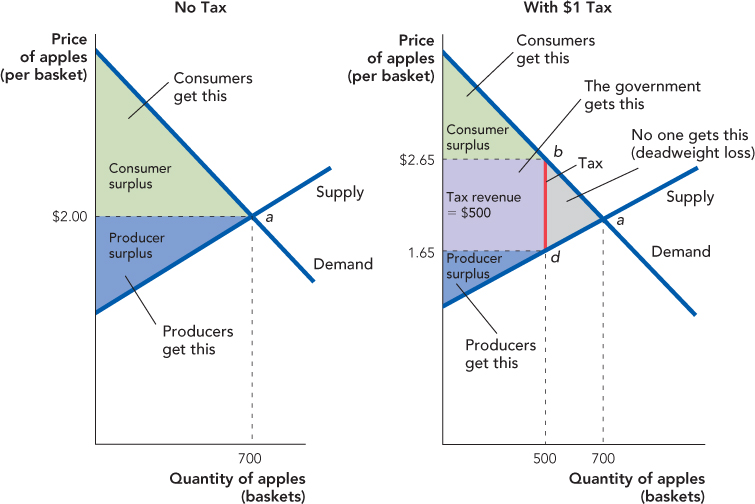

A Commodity Tax Raises Revenue and Creates a Deadweight Loss (Reduces the Gains from Trade)

A tax generates revenues for the government but also creates a deadweight loss (i.e., reduces the gains from trade). In the left panel of Figure 6.5, we show the apple market with no tax; the equilibrium price is $2 and the equilibrium quantity is 700. Consumer surplus is shown in green and producer surplus is shown in blue. As emphasized in Chapter 4, in a free market trade occurs whenever the buyer’s willingness to pay exceeds the supplier’s willingness to sell (i.e., whenever the demand curve lies above the supply curve). A free market maximizes the gains from trade, the sum of consumer and producer surplus.

103

In the right panel, we show the same market with a $1 tax (this is identical to Figure 6.3 only this time we have labeled some of the areas). The tax is $1 per basket and 500 baskets are traded, so tax revenues are shown by the purple rectangle and are equal to $500 = $1 × 500.

The tax decreases consumer and producer surplus, as you can see by comparing the green and blue areas in the left and right panels. Some of the consumer and producer surplus is transferred to the government in the form of tax revenues, but notice that consumer and producer surplus together decrease by more than government revenue increases—the difference is the gray triangle (abd) labeled “deadweight loss.”

To understand why a tax creates a deadweight loss, let’s take a simple case. Imagine that you are willing to pay $50 for a bus ride to New York City when the price of a ticket is $40. Thus, you take the trip and earn $10 in consumer surplus ($50 − $40). Now suppose the government imposes a $20 tax, which increases the price of the ticket to $60. Do you take the trip? No, since the price of the ticket now exceeds your willingness to pay, you do not go to New York City. Thus, you lose $10 in consumer surplus. Does the government gain any tax revenue? No. Your loss of $10 is not compensated for by any increase in government revenue and thus is a deadweight loss. In short, the deadweight loss of a tax is the lost gains from the trips (trades) that do not occur because of the tax.

104

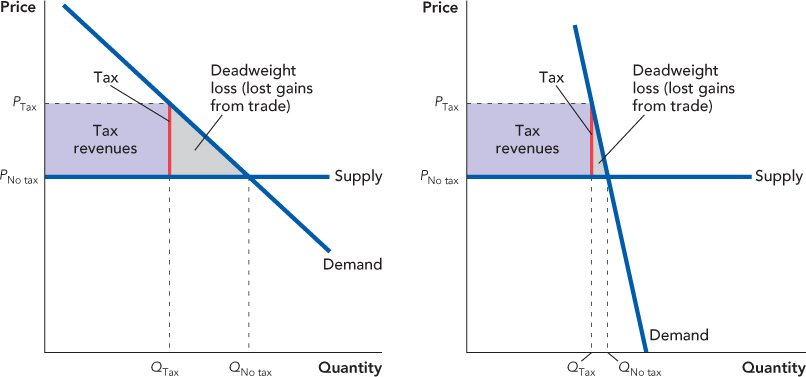

A key factor determining deadweight loss is the elasticities of supply and demand. Figure 6.6, for example, shows that the deadweight loss from taxation is larger the more elastic the demand curve. To understand why, remember that deadweight loss is the lost gains from trade. If the demand curve is relatively elastic, as in the left panel of Figure 6.6, then the tax deters a lot of trades, QTax is much less than QNo tax, so the lost gains from trade are large. It’s just like the bus story—if the demand curve is elastic, then the tax means many lost bus trips.

Elasticity and Deadweight Loss

If the demand is relatively inelastic, however, as in the right panel of Figure 6.6 then the tax does not deter many trades. Notice that QTax is only slightly smaller than QNo tax. Since nearly the same number of trades occur, there are few lost gains from trade. Again, let’s go back to the bus. Imagine that you were willing to pay $100 to go to New York. In that case, if the government taxes you $20, you still take the trip. True, your consumer surplus falls by $20, but the government’s revenues increases by $20—since the trip was not deterred, there is no deadweight loss in this case.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 6.1

Suppose that the government taxes insulin producers $50 per dose produced. Who is likely to ultimately pay this tax?

Suppose that the government taxes insulin producers $50 per dose produced. Who is likely to ultimately pay this tax?

Question 6.2

Although the government taxes almost everything, would the government rather tax items that have relatively inelastic or relatively elastic demands and supplies? Why?

Although the government taxes almost everything, would the government rather tax items that have relatively inelastic or relatively elastic demands and supplies? Why?

Question 6.3

A tax transfers some consumer and some producer surplus into government revenue. Show that when demand is more elastic than supply, producers lose more surplus than consumers lose, and vice-versa.

A tax transfers some consumer and some producer surplus into government revenue. Show that when demand is more elastic than supply, producers lose more surplus than consumers lose, and vice-versa.

The same intuition also explains why the deadweight loss from taxation (holding tax revenue constant) is lower the less elastic the supply curve. If the supply curve is elastic, then the tax deters many trades, but if the supply curve is inelastic, there is little deterrence and thus few lost gains from trade.

Recall from Chapter 5 that the demand curve for fruit will tend to be less elastic (more inelastic) than the demand curve for apples because there are fewer substitutes for fruit than there are for apples. Thus, an equal-revenue tax on fruit would generate less deadweight loss than a tax on apples. By the same reasoning, a tax on food would generate less deadweight loss than one on fruit, and a tax on all consumption goods would generate even less deadweight loss than an equal-revenue tax on food. The lesson is that broad-based taxes will tend to create less deadweight loss than more narrowly based taxes. Of course, there can be exceptions. We might want to tax bads such as pollution more than goods. We take up the taxation of bads in Chapter 10.

105

Even though taxes create a deadweight loss, they also pay for beneficial goods and services. In Chapter 19, we discuss in more detail when the goods that taxation provides are likely to have benefits that exceed the deadweight loss caused by taxation.