7.1 CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 7.8

1.Suppose you’d like to do five different things, each of which requires exactly one orange. Complete the following table, ranking your highest-valued orange-related activity (1) to your lowest-valued activity (5).

Activity

Rank of Preference

Give a friend the orange.

Throw the orange at a person you don’t like.

Eat the orange.

Squeeze the orange to drink the juice.

Use the orange as decorative fruit.

128

Suppose the price per orange is high enough that you buy only four. What activity do you not do?

How low would the price of oranges have to fall for you to purchase five oranges? What does the price at which you would just purchase the fifth orange tell us about the value you receive from the fifth-ranked activity?

Question 7.9

2. The supply and demand for copper change constantly. New sources are discovered, mines collapse, workers go on strike, products that use it wane in and out of popularity, weather affects shipping conditions, and so on.

Suppose you learned that growing political instability in Chile (the largest producer of copper) will greatly reduce the productivity of its mines in two years. Ignoring all other factors, which curve (demand or supply) will shift which way in the market for copper two years from now?

Will the price rise or fall as a result of this curve shift?

Given your answer in part b, would a reasonable person buy copper to store for later? Why or why not? Ignore storage costs.

As a result of many people imitating your choice in part c, what happens to the current price of copper?

Does the action in parts c and d encourage people to use more copper today or less copper today?

Question 7.10

3. In this chapter, we noted that successful economies are more likely to have many failing firms. If a nation’s government instead made it impossible for inefficient firms to fail by giving them loans, cash grants, and other bailouts to stay in business, why is that nation likely to be poor? (Hint: Steven Davis and John Haltiwanger. 1999. “Gross Job Flows.” In Handbook of Labor Economics [Amsterdam: North-Holland] found that in the United States, 60% of the increase in U.S. manufacturing efficiency was caused by people moving from weak firms to strong firms.)

Question 7.11

4. For you, personally, what is your opportunity cost of doing this homework?

Question 7.12

5. Suppose you are bidding on a used car and someone else bids above the highest amount that you are willing to pay. What can you say for sure about that person’s monetary value of the good compared to yours?

Question 7.13

6. Sometimes speculators get it wrong. In the months before the Persian Gulf War, speculators drove up the price of oil: The average price in October 1990 was $36 per barrel, more than double its price in 1988. Oil speculators, like many people around the world, expected the Gulf War to last for months, disrupting the oil supply throughout the Gulf region. Thus, speculators either bought oil on the open market (almost always at the high speculative price) or they already owned oil and just kept it in storage. Either way, their plan was the same: to sell it in the future, when prices might even be higher.

As it turned out, the war was swift: After one month of massive aerial bombardment of Iraqi troops and a 100-hour ground war, then President George H. W. Bush declared a cessation of hostilities. Despite the fact that Saddam Hussein set fire to many of Kuwait’s oil fields, the price of oil plummeted to about $20 per barrel, a price at which it remained for years.

Is buying oil for $36 a barrel and selling it for $20 per barrel a good business plan? How much profit did speculators earn, or how much money did they lose, on each barrel?

Why did the speculators follow this plan?

When the speculators sold their stored oil in the months after the war, did this massive resale tend to increase the price of oil or decrease it?

129

Do you think that many consumers complained about speculators or even realized that speculators were influencing the price of oil in spring 1991?

Question 7.14

7. You manage a department store in Florida, and one winter day you read in the newspaper that orange juice futures have fallen dramatically in price. Should your store stock up on more sweaters than usual, or should your store stock up on more Bermuda shorts?

Question 7.15

8. Take a look at Figure 7.3. If investors in the Hollywood Stock Exchange were too optimistic on average, would the dots tend to cluster above the red diagonal line or below it? How can you tell?

Question 7.16

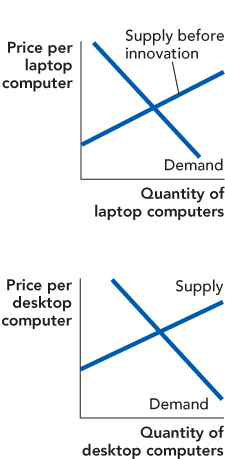

9. Let’s see if the forces of the market can be as efficient as a benevolent dictator. Since laptop computers are increasingly easy to build and since they allow people to use their computers wherever they like, an all-wise benevolent dictator would probably decree that most people buy laptops rather than desktop computers. This is especially true now that laptops are about as powerful as most desktops. In answering questions a–c, answer in words as well as by shifting the appropriate curves in the following figures.

Since it’s become much easier to build better laptops in recent years, laptop supply has increased. What does this do to the price of laptops?

Laptops and desktops are substitutes. Now that the price of laptops has changed, what does this do to the demand for desktop computers?

And how does that affect the quantity supplied of desktop computers?

Now let’s look at the final result: Once it became easier to build good laptops, did “invisible hand” forces push more of society’s resources into making laptops and push resources away from making desktops? (Note: Laptop sales first outnumbered desktop sales in 2008.)

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 7.17

1. Andy enters into a futures contract, allowing him to sell 5,000 troy ounces of gold at $1,000 per ounce in 36 months. After that time passes, the market price of gold is $950 per troy ounce. How much does Andy make or lose?

Question 7.18

2. Circa 1200 BCE, a decreasing supply of tin due to wars and the breakdown of trade led to a drastic increase in the price of bronze in the Middle East and Greece (tin being necessary for its production). It is around this time that blacksmiths developed iron- and steel-making techniques (as substitutes for bronze).

How is the increasing price of bronze a signal?

How is the increasing price an incentive?

How do your answers in parts a and b help explain why iron and steel became more common around the same time as the increase in price?

After the development of iron, did the supply or demand for bronze shift? Which way did it shift? Why?

Question 7.19

3. In 1980, University of Maryland economist Julian Simon bet Stanford entomologist Paul Ehrlich that the price of any five metals of Ehrlich’s choosing would fall over 10 years. Ehrlich believed that resources would become scarcer over time as the population grew, while Simon believed that people would find good substitutes, just as earlier people developed iron as a substitute for scarce bronze. The price of all five metals that Ehrlich chose (nickel, tin, tungsten, chromium, and copper) fell over the next 10 years and Simon won the bet. Ehrlich, an honorable man, sent a check in the appropriate amount to Simon.

130

What does the falling price tell us about the relative scarcity of these metals?

What could have shifted to push these prices down: demand or supply? And would demand have increased or decreased? And supply?

Question 7.20

4. In this chapter, we explored how prices tie all goods together. To illustrate this idea, suppose new farming techniques drastically increased the productivity of growing wheat.

Given this change, how would the price of wheat change?

Given your answer in part a, how would the price of cookbooks specializing in recipes using wheat flour change?

Given your answer in part b, how would the price of paper change?

Given your answer in part c, how would the price of pencils change? (Hint: Are paper and pencils substitutes or complements?)

Given your answer in part d, how would the quantity of graphite (used in pencils) consumed change?

Question 7.21

5. The law of one price states that if it’s easy to move a good from one place to another, the price of identical goods will be the same because traders will buy low in one region and sell high in another. How is our story about the effect of speculators similar to the lesson about the law of one price?

Question 7.22

6. Let’s build on this chapter’s example of asphalt. Suppose a new invention comes along that makes it easier and much less expensive to recycle clothing: Perhaps a new device about the size of a washing machine can bleach, reweave, and redye cotton fabric to closely imitate any cotton item you see in a fashion magazine. Head into the laundry room, drop in a batch of old clothes, scan in a couple of pages from Vogue, and come back in an hour.

If you think of the “market for clothing” as “the market for new clothing,” does this shift the demand or the supply curve, and in which direction?

If you think of the “market for clothing” as “the market for clothing, whether it’s new or used,” does this shift the demand or the supply curve, and in which direction?

What will this do to the price of new, unrecycled clothing?

After this invention, will society’s scarce productive resources (machines, workers, retail space) flow toward the “new clothing” sector or away from it?

(Note: This question might sound fanciful but three-dimensional printers, which can create plastic or plaster prototypes of small items such as toys, cups, etc., have fallen dramatically in price. Every day, you’re getting just a little bit closer to having your own personal Star Trek replicator.)

Question 7.23

7. Robin is planning to ask Peggy to the Homecoming dance. Before he asks her, he wants to know what the chances are that she’ll say yes. Robin is a scientist so he considers two paths to estimate the probability that Peggy will say yes.

Ask 10 of his friends, “Do you think she’ll really say yes?”

Tell another 10 of his friends, “I’m starting a betting market. I’ll pay $10 if she says yes, $0 if she says no. I’m offering this bet only once, to the highest bidder. Start bidding against each other for a chance at $10!”

According to the evidence in this chapter, one of these methods will work better. Which one, and why?

If the highest bid from Group II is $1 (along with a few lower bids of $0.75, $0.50, and zero), then roughly what’s the chance that Peggy will say yes to Robin?

If the highest bid from Group II quickly shoots up to about $9, then what’s the chance that Peggy will say yes to Robin?

Question 7.24

8. A classic essay about how markets link to each other is entitled “I, Pencil,” written by Leonard E. Read (his real name). It is available for free online at the Library of Economics and Liberty. As you might suspect, it is written from the point of view of a pencil. One line is particularly famous: “No single person on the face of this earth knows how to make me.” Based on what you’ve learned in this chapter about how markets link the world, how is this true?

131

CHALLENGES

Question 7.25

1. In The Fatal Conceit, economist Friedrich A. Hayek, arguing against central planning, wrote: “The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.” In other words, people generally assume that they can plan out the best procedure for producing a good (such as the Valentine’s Day rose mentioned at the beginning of the chapter), but as we learned, that’s not true. What are some of the different roles that the price system plays in creating this order? (Hint: Key words are “links,” “signals,” and “incentives.”)

Question 7.26

2. One question that economics students often ask is, “In a market with a lot of buyers and sellers, who sets the price of the good?” There are two possible correct answers to this question: “Everyone” and “No one.” Choose one of the two as your answer, and explain in one or two sentences why you are correct.

Question 7.27

3. This chapter emphasized the ability of an orderly system to emerge without someone explicitly designing the entire system. How does the evolution of language illustrate a type of spontaneous order?

Question 7.28

4. Are you in favor of “price gouging” during natural disasters? Why or why not?

Question 7.29

5. What is the opportunity cost of the economics profession?

!launch! WORK IT OUT

Two major-party presidential candidates are running against each other in the 2016 election. The Democratic Party candidate promises more money for corn-based ethanol research, and the Republican Party candidate promises more money for defense contractors. In the weeks before the election, defense stocks take a nosedive.

Who is probably going to win the election: the pro-ethanol candidate or the prodefense spending candidate?

We talked about how price signals are sometimes noisy. Think of two or three other markets you might want to look at to see if your answer to part a is correct.

132