8.1 CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 8.9

1. How does a free market eliminate a shortage?

Question 8.10

2. When a price ceiling is in place keeping the price below the market price, what’s larger: quantity demanded or quantity supplied? How does this explain the long lines and wasteful searches we see in price-controlled markets?

Question 8.11

3. Suppose that the quantity demanded and quantity supplied in the market for milk is as follows:

|

Price per Gallon |

Quantity Demanded |

Quantity Supplied |

|---|---|---|

|

$5 |

1,000 |

5,000 |

|

$4 |

2,000 |

4,500 |

|

$3 |

3,500 |

3,500 |

|

$2 |

4,100 |

2,000 |

|

$1 |

6,000 |

1,000 |

155

What is the equilibrium price and quantity of milk?

If the government places a price ceiling of $2 on milk, will there be a shortage or surplus of milk? How large will it be? How many gallons of milk will be sold?

Question 8.12

4. If a government decides to make health insurance affordable by requiring all health insurance companies to cut their prices by 30%, what will probably happen to the number of people covered by health insurance?

Question 8.13

5. The Canadian government has wage controls for medical doctors. To keep things simple, let’s assume that they set one wage for all doctors: $100,000 per year. It takes about 6 years to become a general practitioner or a pediatrician, but it takes about 8 or 9 years to become a specialist like a gynecologist, surgeon, or ophthalmologist. What kind of doctor would you want to become under this system? (Note: The actual Canadian system does allow specialists to earn a bit more than general practitioners, but the difference isn’t big enough to matter.)

Question 8.14

6. Between 2000 and 2008, the price of oil increased from $30 per barrel to $140 per barrel, and the price of gasoline in the United States rose from about $1.50 per gallon to more than $4.00 per gallon. Unlike in the 1970s when oil prices spiked, there were no long lines outside gas stations. Why?

Question 8.15

7. Price controls distribute resources in many unintended ways. In the following cases, who will probably spend more time waiting in line to get scarce, price-controlled goods? Choose one from each pair:

Working people or retired people?

Lawyers who charge $800 per hour or fast-food employees who earn $8 per hour?

People with desk jobs or people who can disappear for a couple of hours during the day?

Question 8.16

8. In the chapter, we discussed how price ceilings can put goods in the wrong place, as when too little heating oil wound up in New Jersey during a harsh winter in the 1970s. Price controls can also put goods in the wrong time as well. If there are price controls on gasoline, can you think of some periods during which the shortage will get worse? (Hint: Gas prices typically rise during the busy Memorial Day and Labor Day weekends.)

Question 8.17

9.

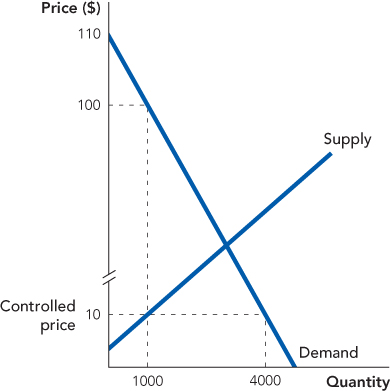

Consider Figure 8.8. In a price-controlled market like this one, when will consumer surplus be larger: in the short run or in the long run?

In this market, supply is more elastic, more flexible, in the long run. In other words, in the longer term, landlords and homebuilders can find something else to do for a living. In light of this and in light of the geometry of producer surplus in this figure, do rent controls hurt landlords and homebuilders more in the short run or in the long run?

Question 8.18

10. Business leaders often say that there is a “shortage” of skilled workers, and so they argue that immigrants need to be brought in to do these jobs. For example, an AP article was entitled “New York farmers fear a shortage of skilled workers,” and went on to point out that a special U.S. visa program, the H-2A program, “allows employers to hire foreign workers temporarily if they show that they were not able to find U.S. workers for the jobs.”(Source: Thompson, Carolyn. May 13, 2008. N.Y. farmers fear a shortage of skilled workers. Associated Press.)

How do unregulated markets cure a “labor shortage” when there are no immigrants to boost the labor supply?

Why are businesses reluctant to let unregulated markets cure the shortage?

Question 8.19

11.

If the government forced all bread manufacturers to sell their products at a “fair price” that was half the current, free-market price, what would happen to the quantity supplied of bread?

To keep it simple, assume that people must wait in line to get bread at the controlled price. Would consumer surplus rise, fall, or can’t you tell with the information given?

With these price controls on bread, would you expect bread quality to rise or fall?

Question 8.20

12. A review of the jargon: Is the minimum wage a “price ceiling” or a “price floor”? What about rent control?

Question 8.21

13. How do U.S. business owners change their behavior when the minimum wage rises? How does this impact teenagers?

156

Question 8.22

14. The basic idea of deadweight loss is a willing buyer and a willing seller can’t find a way to make an exchange. In the case of the minimum wage law, the reason they can’t make an exchange is because it’s illegal for the buyer (the firm) to hire the seller (the worker) at any wage below the legal minimum. But how can this really be a “loss” from the worker’s point of view? It’s obvious why business owners would love to hire workers for less than the minimum wage, but if all companies obey the minimum wage law, why are some workers still willing to work for less than that?

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 8.23

1. In rich countries, governments almost always set the fares for taxi rides. The prices for taxi rides are the same in safe neighborhoods and in dangerous neighborhoods. Where is it easier to find a cab? Why? If these taxi price controls were ended, what would probably happen to the price and quantity of cab rides in dangerous neighborhoods?

Question 8.24

2. When the United States had price controls on oil and gasoline, some parts of the United States had a lot of heating oil, while other states had long lines. As in the chapter, let’s assume that winter oil demand is higher in New Jersey than in California. If there had been no price controls, what would have happened to the prices of heating oil in New Jersey and in California and how would “greedy businesspeople” have responded to these price differences?

Question 8.25

3. On January 31, 1990, the first McDonald’s opened in Moscow, capital of the then Soviet Union. Economists often described the Soviet Union as a “permanent shortage economy,” where the government kept prices permanently low in order to appear “fair.”

“An American journalist on the scene reported the customers seemed most amazed at the ‘simple sight of polite shop workers … in this nation of commercial boorishness.’”

(Source: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-mcdonalds-opens-in-soviet-union.)

Why were most Soviet shop workers “boorish” when the McDonald’s workers in Moscow were “polite”?

What does your answer to the previous question tell you about the power of economic incentives to change human behavior? In other words, how entrenched is “culture”?

Question 8.26

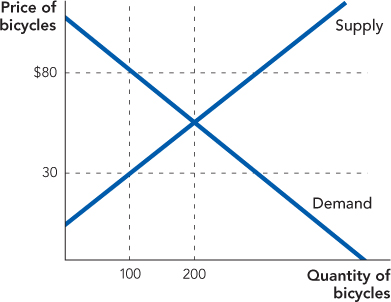

4. Let’s count the value of lost gains from trade in a regulated market. The government decides it wants to make basic bicycles more affordable, so it passes a law requiring that all one-speed bicycles sell for $30, well below the market price. Use the following data to calculate the lost gains from trade, just as in Figure 8.3. Supply and demand are straight lines.

What is the total value of wasted time in the price-controlled market?

What is the value of the lost gains from trade?

Note that we haven’t given you the original market price of simple bicycles—why don’t you need to know it? (Hint: The answer is a mix of geometry and economics.)

Question 8.27

5. During a crisis such as Hurricane Sandy, governments often make it illegal to raise the price of emergency items like flashlights and bottled water. In practice, this means that these items get sold on a first-come/first-served basis.

157

If a person has a flashlight that she values at $5, but its price on the black market is $40, what gains from trade are lost if the government shuts down the black market?

Why might a person want to sell a flashlight for $40 during an emergency?

Why might a person be willing to pay $40 for a flashlight during an emergency?

When will entrepreneurs be more likely to fill up their pickup trucks with flashlights and drive into a disaster area: when they can sell their flashlights for $5 each or when they can sell them for $40 each?

Question 8.28

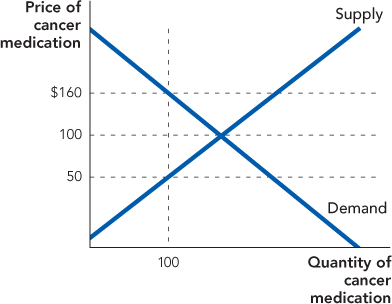

6. A “black market” is a place where people make illegal trades in goods and services. For instance, during the Soviet era, it was common for American tourists to take a few extra pairs of Levi’s jeans when visiting the Soviet Union: They would sell the extra pairs at high prices on the illegal black market.

Consider the following claim: “Price-controlled markets tend to create black markets.” Let’s illustrate with the following figure. If there is a price ceiling in the market for cancer medication of $50 per pill, what is the widest price range within which you can definitely find both a buyer and a seller who would be willing to illegally exchange a pill for money? (There is only one correct answer.)

Question 8.29

7. So, knowing what you know now about price controls, are you in favor of setting a $2 per gallon price ceiling on gasoline? Create a pro–price control and an anti–price control answer.

Question 8.30

8.

As we noted, Assar Lindbeck once said that short of aerial bombardment, rent control is the best way to destroy a city. What do you think Lindbeck might mean by this?

How does paying “key money” to a landlord reduce the severity of Lindbeck’s “bombardment”?

Question 8.31

9. In the town of Freedonia, the government declares that all street parking must be free: There can be no parking meters. In an almost identical town of Meterville, parking costs $5 per hour (or $1.25 per 15 minutes).

Where will it be easier to find parking: in Freedonia or Meterville?

One town will tend to attract shoppers who hate driving around looking for parking. Which one?

Why will the town from part b also attract shoppers with higher incomes?

Question 8.32

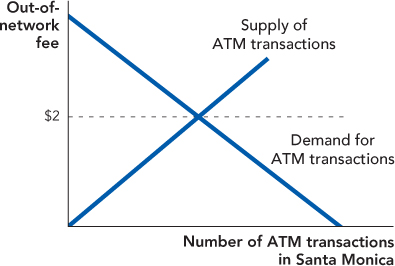

10. In the late 1990s, the town of Santa Monica, California, made it illegal for banks to charge people ATM fees. As you probably know, it’s almost always free to use your own bank’s ATMs, but there’s usually a fee charged when you use another bank’s ATM. (Source: The war on ATM fees, Time, November 29, 1999.) As soon as Santa Monica passed this law, Bank of America stopped allowing cus tomers from other banks to use their ATMs: In bank jargon, B of A banned “out-of-network” ATM usage.

In fact, this ban lasted for only a few days, after which a judge allowed banks to continue to charge fees while awaiting a full court hearing on the issue. Eventually, the court declared the fee ban illegal under federal law. But let’s imagine the effect of a full ban on out-of-network fees.

In the figure, indicate the new price per out-of-network ATM transaction after the fee ban. Also clearly label the shortage.

158

Calculate the exact amount of producer and consumer surplus in the out-of-network ATM market in Santa Monica after the ban. How large is producer surplus? How large is consumer surplus?

Question 8.33

11. Consider Figure 8.9. Your classmate looks at that chart and says, “Apartment construction slowed down years before rent control was passed, and after rent control was passed, more apartments were built. Rent control didn’t cut the number of new apartments, it raised it. This proves that rent control works.” What is wrong with this argument?

Question 8.34

12. Rent control creates a shortage of housing, which makes it hard to find a place to live. In a price-controlled market, people have to waste a lot of time trying to find these scarce, artificially cheap products. Yet Congressman Charles B. Rangel, the chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, lived in four rent-stabilized apartments in Harlem. Why are powerful individuals often able to “find” price-controlled goods much more often than the nonpowerful? What does this tell us about the political side effects of price controls? (Source: Republicans question Rangel’s tax break support, The New York Times, November 25, 2008.)

Question 8.35

13. In the 1970s, AirCal and Pacific Southwest Airlines flew only within California. As we mentioned, the federal price floors didn’t apply to flights within just one state. A major route for these airlines was flying from San Francisco to Los Angeles, a distance of 350 miles. This is about the same distance as from Chicago, Illinois, to Cleveland, Ohio. Do you think AirCal flights had nicer meals than flights from Chicago to Cleveland? Why or why not?

Question 8.36

14. President Jimmy Carter didn’t just deregulate airline prices. He also deregulated much of the trucking industry as well. Trucks carry almost all of the consumer goods that you purchase, so almost every time you purchase something, you’re paying money to a trucking company.

Based on what happened in the airline industry after prices were deregulated, what do you think happened in the trucking industry after deregulation? You can find some answers here: http://www.econlib.org/Library/Enc1/TruckingDeregulation.html. For another look that is critical of trucking deregulation, but comes to basically the same answers, see Michael Belzer, 2000. Sweatshops on Wheels: Winners and Losers in Trucking Deregulation. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Who do you think asked Congress and the president to keep price floors for trucking: consumer groups, retail shops like Walmart, or the trucking companies?

Question 8.37

15. Suppose you’re doing some history research on shoe production in ancient Rome, during the reign of the famous Emperor Diocletian. Your records tell you how many shoes were produced each year in the Roman Empire, but it doesn’t tell you the price of shoes.

You find a document stating that in the year 301, Emperor Diocletian issued an “edict on prices,” but you don’t know whether he imposed price ceilings or price floors—your Latin is a little rusty. However, you can clearly tell from the documents that the number of shoes actually exchanged in markets fell dramatically, and that both potential shoe sellers and potential shoe buyers were unhappy with the edict. With the information given, can you tell whether Diocletian imposed a ceiling or a floor? If so, which is it? (Yes, there really was an edict of Diocletian, and Wikipedia has excellent coverage of ancient Roman history.)

Question 8.38

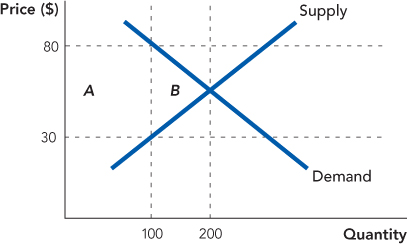

16. In the market depicted in the figure, there is either a price ceiling or a price floor—surprisingly, it doesn’t matter which one it is: Whether it’s an $80 price floor or a $30 price ceiling, the chart looks the same.

In the chart, there’s a rectangle and a triangle. One represents the value lost from the “deals that don’t get made” and one represents the value lost from “the deals that do get made.” Which is which?

159

Question 8.39

17. We noted that in the 1970s price floors on airline tickets caused wasteful increases in the quality of airline trips. Does the minimum wage cause wasteful increases in the quality of workers? If so, how? In other words, how are minimum-wage workers like airplane trips?

CHALLENGES

Question 8.40

1. If a government decided to impose price controls on gasoline, what could it do to avoid the time wasted waiting in lines? There is surely more than one solution to this problem.

Question 8.41

2. In New York City, some apartments are under strict rent control, while others are not. This is a theme in many novels and movies about New York, including Bonfire of the Vanities and When Harry Met Sally. One predictable side effect of rent control is the creation of a black market. Let’s think about whether it’s a good idea to allow this black market to exist.

Harry is lucky enough to get a rent-controlled apartment for $300 per month. The market rent on such an apartment is $3,000 per month. Harry himself values the apartment at $2,000 per month, and he’d be quite happy with a regular $2,000 per month New York apartment. If he stays in the apartment, how much consumer surplus does he enjoy?

If he illegally subleases his apartment to Sally on the black market for $2,500 per month and instead rents a $2,000 apartment, is he better off or worse off than if he obeyed the law?

Question 8.42

3. Let’s measure consumer surplus if the government imposes price controls and goods ended up being randomly allocated among those con sumers willing to pay the controlled price. If the demand and supply curves are as in the figure, then:

What is consumer surplus under the price control?

What would consumer surplus be if the quantity supplied were 1,000 but the goods were allocated to the highest-value users?

Question 8.43

4. Antibiotics are often given to people with colds (even though they are not useful for that purpose), but they are also used to treat life-threatening infections. If there was a price control on antibiotics, what do you think would happen to the allocation of antibiotics across these two uses?

Question 8.44

5. In a command economy such as the old Soviet Union, there were no prices for almost all goods. Instead, goods were allocated by a “central planner.” Suppose that a good like oil becomes more scarce. What problems would a central planner face in reallocating oil to maximize consumer plus producer surplus?

Question 8.45

6. Labor unions are some of the strongest proponents of the minimum wage. Yet in 2008, the median full-time union member earned $886 per week, an average of over $22 per hour (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm). Therefore, a rise in the minimum wage doesn’t directly raise the wage of many union workers. So why do unions support minimum wage laws? Surely, there’s more than one reason why this is so, but let’s see if economic theory can shed some light on the subject.

160

Skilled and unskilled labor are substitutes: For example, imagine that you can hire four low-skilled workers to move dirt with shovels at $5 an hour, or you can hire one skilled worker at $24 an hour to move the same amount of dirt with a skid loader. Using the tools developed in Chapter 3, what will happen to the demand for skilled labor if the price of unskilled labor increases to $6.50 per hour?

If the minimum wage rises, will that increase or decrease the demand for the average union worker’s labor? Why?

Now, let’s put the pieces together: Why might high-wage labor unions support an increase in the minimum wage?

!launch! WORK IT OUT

Suppose that the market for coats can be described as follows:

|

Price |

Quantity Demanded (millions) 16 |

Quantity Supplied (millions) |

|---|---|---|

|

$120 |

16 |

20 |

|

$100 |

18 |

18 |

|

$80 |

20 |

16 |

|

$60 |

22 |

14 |

What are the equilibrium price and quantity of coats?

Suppose the government sets a price ceiling of $80. Will there be a shortage, and if so, how large will it be?

Given that the government sets a price ceiling of $80, how much will demanders be willing to pay per unit of the good (i.e., what is the true price)? Suppose that people line up to get this good and that they value their time at $10 an hour. For how long will people wait in line to obtain a coat?