The Costs of Protectionism

Now that we know that a tariff on an imported good will increase domestic production and decrease domestic consumption, we can analyze in more detail the costs of protectionism. The U.S. government, for example, greatly restricts the amount of sugar that can be imported into the United States. As a result, U.S. consumers pay more than double the world price for sugar—in the early 2000s, U.S. consumers paid about 20 cents per pound of sugar compared with a world price of around 9 cents per pound. So, let’s look in more detail at the costs of sugar protectionism.

164

To simplify our analysis, we make two assumptions. First, we assume that the tariff is so high that it completely eliminates all sugar imports. Although a small amount of sugar is allowed into the United States at a low tariff rate, anything above this small amount is taxed so heavily that no further imports occur. Our assumption that the tariff eliminates all sugar imports is not a bad approximation to what actually happens. Second, we assume that if we had complete free trade, all sugar would be imported. This is also a reasonable assumption because, as we will explain shortly, sugar can be produced elsewhere at much lower cost than in the United States. Making these two assumptions will focus attention on the key ideas. See question 1 in the end-of-chapter Challenges section for a more detailed analysis.

SEARCH ENGINE

Information on sugar and the U.S. sugar tariff can be found from the USDA Economic Research Service, Sugar Briefing Room.

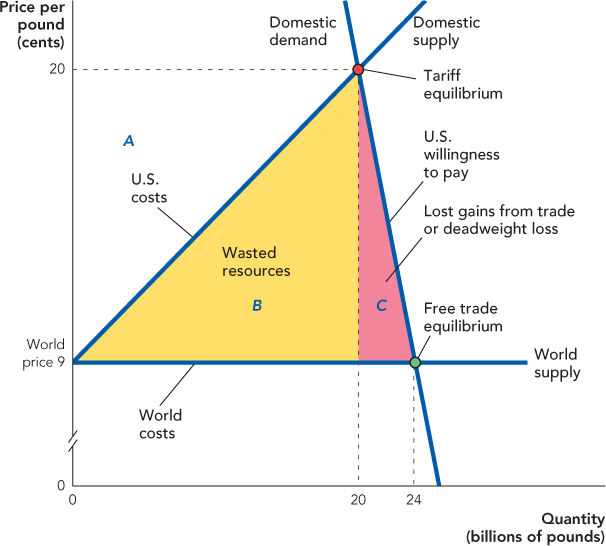

In Figure 9.3, we show the market for sugar. If there were complete free trade in sugar, U.S. consumers would be able to buy at the world price of 9 cents per pound and they would purchase 24 billion pounds. U.S. producers cannot compete with foreign producers at a price of 9 cents per pound so with free trade all sugar would be imported.

165

The tariff on sugar imports is so high that with the tariff there are no imports and the U.S. price of sugar—found at the intersection of the domestic demand and domestic supply curve—rises to 20 cents per pound.

Recall that a tariff has two effects: It increases domestic production and reduces domestic consumption. Each of these effects has a cost. First, the increase in domestic production may sound good—and it is good for domestic producers—but domestic producers have higher costs of production than foreign producers. Thus, the tariff means that sugar is no longer supplied by the lowest-cost sellers and resources that could have been used to produce other goods and services are instead wasted producing sugar. Second, due to higher costs, the price of sugar rises and fewer people buy sugar, reducing the gains from trade. Let’s look at each of these costs in more detail.

Sugar costs more to grow in the United States than in, say, Brazil, the world’s largest producer of sugar, because the climate in the U.S. mainland is not ideal for sugar growing and because land and labor in Florida, where a lot of U.S. sugar is grown, have many alternative uses that are high in value. Sugar farmers in Florida, for example, have to douse their land with expensive fertilizers to increase production—in the process creating environmental damage in the Florida Everglades.1 The excess resources—the fertilizer, land, and labor—that go into producing U.S. sugar could have been used to produce other goods like oranges and theme parks for which the United States and Florida are better suited.

Recall from Chapter 3 that the supply curve tells us the cost of production so at the equilibrium price the cost of producing an additional pound of sugar in the United States is exactly 20 cents. In other words, in the United States it takes 20 cents worth of resources like land and labor to produce one additional pound of sugar. That same pound of sugar could be bought in the world market for just 9 cents so the tariff causes 11 cents worth of resources to be wasted in producing that last pound of sugar.

The total value of wasted resources is shown in Figure 9.3 by the yellow area labeled “Wasted resources”; that area represents the difference between what it costs to produce 20 billion pounds of sugar in the United States and what it would cost to buy the same amount from abroad. We can calculate the total value of wasted resources using our formula for the area of a triangle.

The height of the yellow triangle is 20 – 9 or 11 cents per pound, the base is 20 billion pounds, so the area is 110 billion cents, or $1.1 billion. The sugar tariff wastes $1.1 billion worth of resources.

Notice that if the sugar tariff were eliminated, the price of sugar in the United States would fall to the world price of 9 cents per pound and U.S. production would drop from 20 billion pounds to 0 pounds. It’s important to see that the reduction in U.S. production is a benefit of eliminating the tariff because it frees up resources that can be used to produce other goods and services.

There is another cost to the tariff. Remember from Chapter 3 that the demand curve tells us the value of goods to the demanders, so at the equilibrium price demanders are willing to pay up to 20 cents for a pound of sugar. World suppliers, however, are willing to sell sugar at 9 cents per pound. U.S. consumers and world suppliers could make mutually profitable gains from trade, but they are prevented from doing so by the threat of punishment. The value of the lost gains from trade, which economists also call a deadweight loss, is given by the pink area (area C). Again, we can calculate this area using our formula for the area of a triangle ([20 – 9] cents per pound × 4 billion pounds divided by 2) = 22 billion cents or $0.22 billion.

166

To combat this entrepreneurship, the U.S. government created even more tariffs for sugar-containing products like iced tea, cake mixes, and cocoa.

Thus, the total cost of the sugar tariff to U.S. citizens is $1.1 billion of wasted resources plus $0.22 billion of lost gains from trade for a total loss of $1.32 billion.

Do you remember from Chapter 4 the three conditions that explain why a free market is efficient? Here they are again:

The supply of goods is bought by the buyers with the highest willingness to pay.

The supply of goods is sold by the sellers with the lowest costs.

Between buyers and sellers, there are no unexploited gains from trade or any wasteful trades.

A tariff or quota that restricts consumers from trading with foreign producers means that the market is not free, so we should expect some of the conditions in our list to be violated. In this case, conditions 2 and 3 are violated. A tariff reduces efficiency because the supply of goods is no longer sold by the sellers with the lowest costs, and with a tariff, there are unexploited gains from trade between buyers and sellers.

Some of these benefits of trade may sound fairly abstract, but for a lot of people, they are a matter of life and death. If Brazilian sugar cane farmers could sell more of their products to U.S. consumers, many more of the farmers could afford to eat better or to improve their housing with proper water and sewage. But don’t think the United States is the only party at fault here. The Brazilian government places a lot of tariffs on foodstuffs from the United States and for many Brazilians, including the very poor, this makes food more expensive. The end result is that U.S. consumers pay a high price for sugar and poor Brazilians have less to eat and less money to spend when they need to take their kids to the doctor.

Winners and Losers from Trade

We can arrive at this same total loss in another revealing way. The sugar tariff raises the price of sugar to U.S. consumers, which reduces consumer surplus. Recall from Chapter 3 that consumer surplus is the area underneath the demand curve and above the price. Thus, consumer surplus with the tariff is the area above the price of 20 cents and below the demand curve (not all of which is shown in Figure 9.3). As the price falls from 20 cents to 9 cents, consumer surplus increases by area A + B + C, which has a value (check it!) of $2.42 billion. Or, put differently, the tariff costs consumers $2.42 billion in lost consumer surplus.

The tariff increases price, which increases producer surplus, the area above the supply curve and below the price. Thus, the tariff increases U.S. producer surplus by area A, which has a value of $1.10 billion.

Notice that U.S. consumers lose more than twice as much from the tariff as U.S. producers gain. The total loss to U.S. citizens is the $2.42 billion loss to consumers minus the $1.10 billion gain to producers, for a total loss of $1.32 billion a year, exactly as we found before.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 9.1

Who benefits from a tariff? Who loses?

Who benefits from a tariff? Who loses?

Question 9.2

Why does trade protectionism lead to wasted resources?

Why does trade protectionism lead to wasted resources?

Question 9.3

If there are winners and losers from trade restrictions, why do we hear more often from the people who gain from trade restrictions than from the people who lose?

If there are winners and losers from trade restrictions, why do we hear more often from the people who gain from trade restrictions than from the people who lose?

Question 9.4

Identify the deadweight loss area in Figure 9.3 and describe in words what is lost.

Identify the deadweight loss area in Figure 9.3 and describe in words what is lost.

Our two methods of analyzing the cost of the sugar tariff are equivalent, but they emphasize different things. The first method calculates social loss directly and emphasizes where the loss comes from: wasted resources and lost gains from trade. The second method focuses on who gains and who loses. Domestic producers gain but U.S. consumers lose even more.

Why does the government support the U.S. sugar tariff when U.S. consumers lose much more than U.S. producers gain? One clue is that the costs of the sugar tariff are spread over millions of consumers so the costs per consumer are small. The benefits of the tariff, however, flow to a small number of producers, each of whom benefits by millions of dollars. As a result, the producers support and lobby for the tariff much more actively than consumers oppose the tariff. It’s often been said that the rational rule of politics is to spread costs and concentrate benefits.

167

The politics of lobbying point our attention to yet another cost of protectionism. When a country erects a lot of tariffs against foreign competition, the producers in that country will spend a lot of their time, energy, and money lobbying the government for protection. Those same resources could be spent on production and innovation, not lobbying. Protectionism tends to create a society that pits one interest group against the other and seeds social discord. Free trade, in contrast, creates incentives for people to cooperate toward common and profitable ends.