Arguments Against International Trade

It would take several books to analyze all the arguments against international trade. We will take a closer look at some of the most common arguments:

Trade reduces the number of jobs in the United States.

Trade reduces the number of jobs in the United States.

It’s wrong to trade with countries that use child labor.

It’s wrong to trade with countries that use child labor.

We need to keep certain industries at home for reasons of national security.

We need to keep certain industries at home for reasons of national security.

We need to keep certain “key” industries at home because of beneficial spillovers onto other sectors of the economy.

We need to keep certain “key” industries at home because of beneficial spillovers onto other sectors of the economy.

We can increase U.S. well-being with strategic trade protectionism.

We can increase U.S. well-being with strategic trade protectionism.

Trade and Jobs

When the United States reduces tariffs and imports more shirts from Mexico, the U.S. shirt industry will contract. As a result, many people associate free trade with lost jobs. As economists, however, we want to trace the impact of lower tariffs beyond the most immediate and visible effects. So let’s trace what happens when a tariff is lowered, paying particular attention to the effect on jobs.

When the price of shirts falls, U.S. consumers have more money in their pockets that they can use to buy other goods. The increased consumer spending on Scotch tape, bean bag chairs, x-ray tests, and thousands of other goods leads to increased jobs in these industries. These jobs gains may be more difficult to see than the job losses in the U.S. shirt industry but they are no less real. But what about the money that is now going to Mexican shirt producers instead of to U.S. shirt producers? Isn’t it better to “Buy American” and keep this money at home?

When Mexican producers sell shirts in the United States, they are paid in dollars. But what do Mexicans want dollars for? Ultimately, everyone sells in order to buy. Mexican producers might use their dollars to buy U.S. goods. In this case, the increased U.S. spending on imports of Mexican shirts leads directly to increased Mexican spending on U.S. goods (i.e., U.S. exports).

But what happens if the Mexican shirt producers want to buy Mexican goods or European goods rather than U.S. goods? In order to buy Mexican or European goods, the Mexican shirt producers will need pesos or euros. Fortunately, they can trade their dollars for pesos or euros on the foreign exchange market. Suppose the Mexicans trade their dollars to someone in Germany who in return gives them euros. Why would a German want to trade euros for dollars? Remember that people sell in order to buy. Thus, Germans want dollars so that they can buy U.S. goods or U.S. assets. So once again, the increased spending on Mexican shirt imports leads to an increase in U.S. exports (in this case, to Germany) and thus an increase in jobs in U.S. exporting industries.

168

Our thought experiment reveals an important truth: We pay for our imports with exports. Think about it this way: Why would anyone sell us goods if not to get goods in return? Thus, trade does not eliminate jobs—it moves jobs from import-competing industries to export industries. And remember: Although trade does not change the number of jobs, it does raise wages, as we demonstrated in Chapter 2 on comparative advantage.

Of course, it’s traumatic to lose a job and not all workers can easily transfer from shirt making to the industries that expand with trade. But in a dynamic and growing economy, job loss and job gain are two sides of the same coin. Thomas Edison ended the whale oil industry with his invention of the electric lightbulb in 1879. This was bad for whalers but good for people who like to read at night (and very good for the whales). The phonograph destroyed jobs in the piano industry (darn that Edison, again!), CDs destroyed jobs in the record industry, and today MP3s are destroying jobs in the CD industry. And yet somehow with all these jobs being destroyed, employment and the standard of living keep trending upward.

Job destruction is ultimately a healthy part of any growing economy, but that doesn’t mean we have to ignore the costs of transitioning from one job to another. Unemployment insurance, savings, and a strong education system can help workers respond to shocks. Trade restrictions, however, are not a good way to respond to shocks. Trade restrictions save visible jobs, but they destroy jobs that are just as real but harder to see.

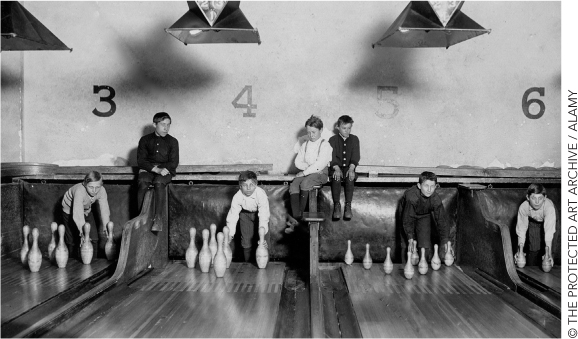

Child Labor

Is child labor a reason to restrict trade? In part, this is a question of ethics on which reasonable people can disagree, but our belief, for which we will give reasons, is that the answer is no.

In 1992, labor activists discovered that Walmart was selling clothing that had been made in Bangladesh by subcontractors who had employed some child workers. Senator Tom Harkin angrily introduced a bill in Congress to prohibit firms from importing any products made by children under the age of 15. Harkin’s bill didn’t pass, but in a panic the garment industry in Bangladesh dismissed 30,000 to 50,000 child workers. A success? Before we decide, we need to think about what happened to the children who were thrown out of work. Where did these children go? To the playground? To school? To a better job? No. Thrown out of the garment factories, the children went to work elsewhere, many at jobs like prostitution with worse conditions and lower pay.2

In 2009, about 18% of all children aged 5–14 around the world worked for a significant number of hours. The vast majority of these children worked in agriculture, often alongside their parents, and not in export industries. Restrictions on trade, therefore, cannot directly reduce the number of child workers, and by making a poor country poorer, trade restrictions may increase the number of child workers. In fact, studies have shown that more openness to trade increases income and reduces child labor.3

169

Child labor is more common in poor countries and it was common in nineteenth-century Great Britain and the United States when people were much poorer than today. Child labor declined in the developed world as people got richer.

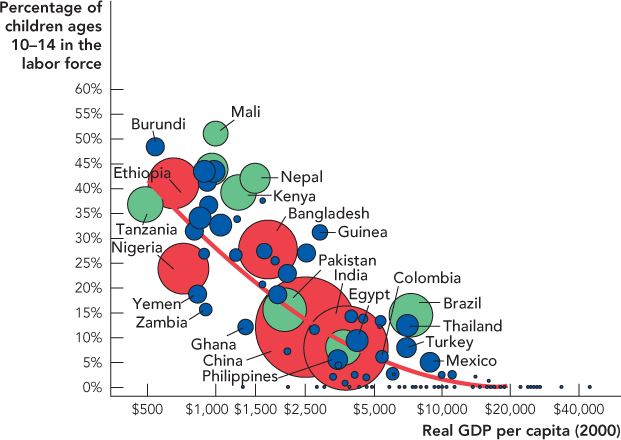

The forces that reduced child labor in the developed world are also at work in the developing world. The vertical axis of Figure 9.4 shows the percentage of children ages 10–14 who are laboring in 132 countries across the world. Real GDP per capita is shown on the horizontal axis. The sizes of the circles are proportionate to the total number of child laborers, so although the percentage of child laborers is much higher in Burundi (48.5%) than in India (12%), there are many more child laborers in India. The lesson of Figure 9.4 is that economic growth reduces child labor.

Note: Ratio Scale

The real cause of child labor is poverty, not trade. Thus, to reduce child labor, we should focus on reducing poverty rather than on reducing trade; putting up trade barriers is likely to be ineffective or even counterproductive.

170

Governments and nonprofits from the developed world can help developing countries reduce child labor by helping them to improve the quality of schooling and to lower the opportunity cost of education. In Bangladesh, at about the same time that child workers were being thrown out of work by the Harkin bill, the government introduced the Food for Education program. The program provides a free monthly stipend of rice or wheat to poor families who have at least one child attending school that month. The program has been very successful at encouraging school attendance. Even more important, increased education of children today means richer parents tomorrow—parents who will no longer feel crushed by the forces of poverty, or in other words parents who will have enough wealth to feed their children and send them to school.4

Trade and National Security

If a good is vital for national security but domestic producers have higher costs than foreign producers, it can make sense for the government to tax imports or subsidize the production of the domestic industry. It may make sense, for example, to support a domestic vaccine industry. In 1918, more than a quarter of the U.S. population got sick with the flu and more than 500,000 died, sometimes within hours of being infected. The young were especially hard-hit and, as a result, life expectancy in the United States dropped by 10 years. No place in the world was safe, as between 2.5% to 5% of the entire world population died from the flu between 1918 and 1920. Producing flu vaccine requires an elaborate process in which robots inject hundreds of millions of eggs with flu viruses. In an ordinary year, there are few problems with buying vaccine produced in another country, but if something like the 1918 flu swept the world again, it would be wise to have significant vaccine production capacity in the United States.5

Don’t be surprised, however, if every domestic producer in trouble claims that their product is vital for national security. Everything from beeswax to mohair, not to mention steel and computer chips, has been protected in the name of national security.

More generally, it’s common for protectionists to lobby under the guise of some other motive. Many people, for example, are legitimately concerned about working conditions in developing countries, but does it surprise you that U.S. labor unions are often the biggest lobbyists for bills to restrict trade on behalf of “oppressed foreign workers”? As Youssef Boutros-Ghali, Egypt’s former minister for trade, put it, “The question is why all of a sudden, when third world labor has proved to be competitive, why do industrial countries start feeling concerned about our workers? … It is suspicious.”6

Key Industries

Another argument that in principle could be true is the “it’s better to produce computer chips than potato chips” argument. The idea is that the production of computer chips is a key industry because it generates spillovers, benefits that go beyond the computer chips themselves (see Chapter 10 for more on spillovers). Protectionism isn’t the best policy in this case (in theory, a subsidy would work better), but if a subsidy isn’t possible, then protectionism might be a second-best policy with some net benefits.

171

The words “in principle” and “might” are well chosen. The “computer chips are better than potato chips” argument can’t be faulted on logic alone, but it’s not very compelling. To address this particular example, most computer chips today are cheap, mass-manufactured commodities. The United States rightly doesn’t specialize in this type of manufacturing and is better off for it, even though this used to be a common argument for protectionism against foreign computer chips.

Second, it is difficult to know which industries are the ones with the really important spillovers. In the late 1980s, many pundits argued that HDTV would be a technology driver for many related industries. Japan and the European Union subsidized their producers to the tune of billions of dollars. The United States lagged behind. In the end, however, Japan and the EU chose an analog technology that is now considered obsolete and HDTV has yet to produce significant benefits for the broader economy, even if it does give you a really nice picture at home.

Strategic Trade Protectionism

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 9.5

Over the past 30 years, most U.S. garment manufacturing has moved overseas, to places such as India and China, where wages are lower. The result of this shift has been a sizable drop in the number of garment workers in the United States. While bad for these workers, why has this trend been a net benefit for the United States?

Over the past 30 years, most U.S. garment manufacturing has moved overseas, to places such as India and China, where wages are lower. The result of this shift has been a sizable drop in the number of garment workers in the United States. While bad for these workers, why has this trend been a net benefit for the United States?

Question 9.6

What would happen if the U.S. government decided that computer chip manufacturing was a strategic national industry and provided monetary grants to Silicon Valley companies? Trace the effects of this policy on Silicon Valley companies, foreign competitors, and the cost and benefit to U.S. taxpayers and consumers.

What would happen if the U.S. government decided that computer chip manufacturing was a strategic national industry and provided monetary grants to Silicon Valley companies? Trace the effects of this policy on Silicon Valley companies, foreign competitors, and the cost and benefit to U.S. taxpayers and consumers.

In some cases, it’s possible for a country to use tariffs and quotas to grab a larger share of the gains from trade than would be possible with pure free trade. The idea is for the government to help domestic firms to act like a cartel when they sell to international buyers. Oddly, the way to do this is to limit or tax exports. A tax or limit on exports reduces exports but can drive up the price enough so that net revenues increase. Of course, this can only work if international buyers have few substitutes for the domestic good. Could this work in practice? Yes, in many ways OPEC is a possible example. OPEC limits exports, and because the demand for oil is inelastic, this increases oil revenues.

Oil is a special good, however, because it is found in large quantities in just a few places in the world. The United States would have a much harder time using strategic trade protectionism because there are more substitutes for U.S.-produced goods. The U.S. economy, or any advanced economy, would also have another problem. Oil is Saudi Arabia’s only significant export so when that nation raises the price of oil, the rest of the world can’t threaten to retaliate by putting tariffs on Saudi Arabia’s other exports. But if the United States were to try to grab a larger share of the gains from trade, in, say, computers, other countries could respond with tariffs on our grain exports. A trade war could easily make both countries worse off. Trying to divide the pie in your favor usually makes the pie smaller.

172