CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 9.7

1. The Japanese people currently pay about four times the world price for rice. If Japan removed its trade barriers so that Japanese consumers could buy rice at the world price, who would be better off and who would be worse off: Japanese consumers or Japanese rice farmers? If we added all the gains and losses to the Japanese, would there be a net gain or net loss? Who would make a greater effort lobbying, for or against, this reduction in trade barriers: Japanese consumers or Japanese rice farmers?

Question 9.8

2. The supply curve for rice in Japan slopes upward, just like any normal supply curve. If Japan eliminated its trade barriers to rice, what would happen to the number of workers employed in the rice-producing industry in Japan: Would it rise or fall? What would these workers probably do over the next year or so? Will they ever work again?

Question 9.9

3. In Figure 9.3, consider triangles B and C. One of these could be labeled “Workers and machines who could be better used in another sector of the economy,” while the other could be labeled “Consumers who have to pay more than necessary for their product.” Which is which?

Question 9.10

4. In his book The Choice, economist Russ Roberts asks how voters would feel about a machine that could convert wheat into automobiles.

Do you think that voters would complain that this machine should be banned, since it would destroy jobs in the auto industry?

Would this machine, in fact, destroy jobs in the auto industry? If so, would roughly the same number of jobs eventually be created in other industries?

Here is Roberts’s punch line: If voters were told that the wonder machine was in fact just a cargo ship that exported wheat and imported autos from a foreign country, how would voters’ attitudes toward this machine change?

Question 9.11

5. Spend some time driving in Detroit, Michigan—the Motor City—and you’re sure to see bumper stickers with messages like “Buy American” or “Out of a job yet? Keep buying foreign!” or “Hungry? Eat your foreign car!” Explain these bumper stickers in light of what you’ve learned in this chapter. Who is hurt by imported automobiles? Who benefits?

Question 9.12

6. This chapter pointed out that trade restrictions on sugar cause U.S. consumers to pay more than twice the going world price for sugar. However, you are very unlikely to ever encounter bumper stickers that say things like “Out of money yet? Keep taxing foreign sugar!” or “Hungry? It’s probably because domestic sugar is so expensive!” Why do you think it is that these bumper stickers are not popular?

Question 9.13

7. Of the three conditions that explain why a free market is efficient (from Chapter 4), which condition or conditions cease to hold in the case of a tariff on imported goods? Which condition or conditions continue to hold even in the case of a tariff on imports?

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 9.14

1.

Just to review: Back in Chapter 8, we illustrated price ceilings with a horizontal line below the equilibrium price. Did price ceilings create surpluses or shortages?

The horizontal line in Figure 9.1 doesn’t represent a surplus or a shortage. What does it represent?

Figure 9.1 considers the case of a country that can buy as many semiconductors as it wants at the same world price. Why do people in this country only buy

units? Why don’t they buy more of this inexpensive product?

units? Why don’t they buy more of this inexpensive product?

Question 9.15

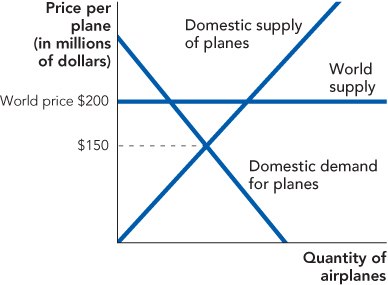

2. Figure 9.1 looks at a case where the world price is below the domestic no-trade price. Let’s look at the case where the world price is above the domestic no-trade price. We’ll work with the market for airplanes shown in the following figure.

In the figure, use the Quantity axis to label

and

and  . This is somewhat similar to Figure 9.1.

. This is somewhat similar to Figure 9.1.What would you call the gap between

and

and  ?

?Also following Figure 9.1, label “Domestic consumption” and “Domestic production.”

Will domestic airplane buyers—airlines and delivery companies like FedEx—have to pay a higher or a lower price under free trade compared with the no-trade alternative? Will domestic airplane buyers purchase a higher or a lower quantity of planes if there’s free trade in planes?

Based on your answer to part d, would you expect domestic airplane demanders to support free trade in planes or oppose it?

Question 9.16

3. In the text, we discuss sugar farmers in Florida who use unusually large amounts of fertilizer to produce their crops; they do so because their land isn’t all that great for sugar production. If we translate this into the language of the supply curve, would these Florida sugar farms be those on the lower-left part of a supply curve or those along the upper right of the supply curve? Why?

Question 9.17

4. Many people will tell you that, whenever possible, you should always buy U.S.-made goods. Some will go further and tell you to spend your money on goods produced in your own state whenever possible. (Just do a simple Google search for “Buy [any state]” and you’ll find a Web site encouraging this kind of thinking.) The idea is that if you spend money in your state, you help the economy of your state, rather than the economy of some other state. By the same logic, shouldn’t one buy only goods produced in one’s own city? Or on one’s own street? Where does this thinking lead to? And how does it relate to Big Idea Five from Chapter 1?

Question 9.18

5. Some people argue for protectionism by pointing out that other countries with whom we trade engage in “unfair trade practices,” and that we should retaliate with our own protectionist measures. One such policy is the policy of some countries to subsidize exporting industries. India, for example, subsidizes its steel industry. Obviously, U.S. steel producers are hurt by this policy and would like to restrict imported steel from India. Is this a good reason to place tariffs on Indian steel? Why or why not?

Question 9.19

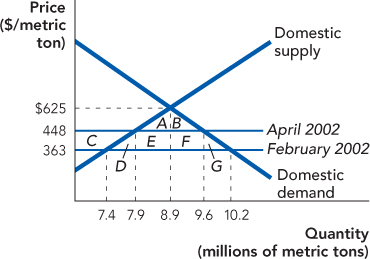

6. In March 2002, then President George W. Bush put a tariff on imported steel as a means of protecting the domestic steel industry. In February, before the tariff went into effect, the U.S. produced 7.4 million metric tons of crude steel and imported about 2.8 million metric tons of steel products at an average price of $363 per metric ton. Two months later, after the tariff was in effect, U.S. production increased to 7.9 million metric tons. The volume of imported steel fell to about 1.7 million metric tons, but the price of the imported steel rose to about $448 per metric ton. The following supply and demand diagram shows this situation (along with an estimated no-trade domestic equilibrium at a price of $625 per metric ton and a quantity of 8.9 million metric tons).

Determine which areas on the graph represent each of the following:

The increase in producer surplus gained by U.S. steel producers as a result of the tariff

The loss in consumer surplus suffered by U.S. steel consumers as a result of the tariff

The revenue earned by the government because of the tariff

The gains from trade that are lost (the deadweight loss) because of the tariff

Question 9.20

7. For each of the four parts of question 6, calculate the values of these areas in dollars. How much of the deadweight loss is due to the overproduction of steel by higher-cost U.S. steel producers, and how much is due to the underconsumption of steel by U.S. steel consumers?

CHALLENGES

Question 9.21

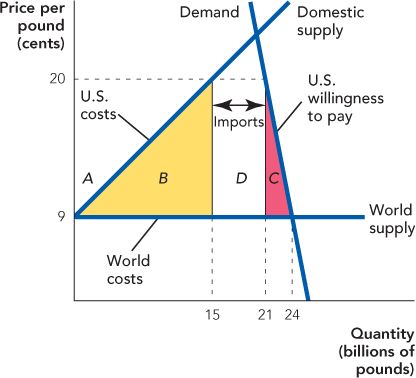

1. In the chapter, we focused on a sugar tariff that eliminated all imports. Let’s now take a look at the case where the sugar tariff eliminates some but not all imports. We will also examine the closely related case of a quota on sugar imports. The figure shows a tariff on sugar that raises the U.S. price to 20 cents per pound but at that price some sugar is imported even after the tariff.

Label the free trade equilibrium, the tariff equilibrium, wasted resources, lost gains from trade, and tariff revenues.

Now imagine that instead of a tariff, the U.S. government uses a quota that forbids imports of sugar greater than 6 billion pounds. (Equivalently, imagine a tariff that is zero on the first 6 billion pounds of imports but then jumps to a prohibitive level after that quantity of imports—this is closer to how the system works in practice.) Under the quota system what does area D represent? Would importers of sugar prefer a tariff or a quota?

The sugar quota is allocated to importing countries based on imports from these countries between 1975 and 1981 (with some subsequent adjustments). For example, in 2008 Australia was given the right to export 87 thousand metric tons of sugar to the United States at a very low tariff rate, and Belize was given the right to export 11.5 thousand metric tons of sugar to the United States at a very low tariff rate. How do you think these rights are allocated to firms within the sugar-exporting countries?

Discuss how the quota and the way it is allocated could create a misallocation of resources that would further reduce efficiency relative to a tariff that resulted in the same quantity of imports.

Question 9.22

2. In a 2005 Washington Post article (“The Road to Riches Is Called K Street”), Jeffrey Birnbaum noted that there were 35,000 registered lobbyists in Washington, D.C., people whose primary job is asking the federal government for something. A lobbyist who comes with long experience as an aide to a powerful politician will earn at least $200,000 per year. Many lobbyists (not all) are attempting to restrict trade in order to turn consumer surplus into producer surplus.

Let’s focus just on the lobbyists who are restricting trade. If the United States were to amend the Constitution to permanently ban all tariffs and trade restrictions, these lobbyists would lose their jobs, and they’d have to leave Washington to get “real jobs.” Would this job change raise U.S. productivity or lower it?

Would most of these lobbyists likely earn more after the amendment was enacted or less?

How can you reconcile your answers to parts a and b?

Question 9.23

3. Let’s think a little more about the Work It Out problem. If quality weren’t held constant, what would you expect to happen to the additional Chinese cars produced after the import ban? Would they be as good as the ones that used to be imported? (Hint: Which types of cars do you think that China imports? Low-quality or high-quality? Why?)

Question 9.24

4. One of the assumptions made in the chapter was that the U.S. market for sugar was small relative to the overall world market for sugar, so that when the United States entered the world market for sugar, and U.S. buyers began to buy imported sugar, the price did not change. If we relax this assumption, how do you think that would affect Figure 9.1? How would the outcome differ from the outcome under the assumption of the relatively small market?

Question 9.25

5. The following tables show the domestic supply and demand schedules for bushels of flaxseed (used as an edible oil and a nutrition supplement) in the United States and Kazakhstan, with prices measured in U.S. dollars and quantities measured in millions of bushels.

In which country is flaxseed cheaper to produce? In which country do the consumers of flaxseed value it more?

Complete the bottom table by describing each nation’s willingness to import or export flaxseed at each price. One row has been done for you as an example.

U.S.

Price

$2

$4

$6

$8

$10

$12

$14

$16

$18

$20

QD

12

11

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

QS

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Kz

Price

$2

$4

$6

$8

$10

$12

$14

$16

$18

$20

QD

5.5

5

4.5

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

QS

1.5

3

4.5

6

7.5

9

10.5

12

13.5

15

At a price of …

the U.S. would be willing to …

and Kazakhstan would be willing to …

$2

import 12 million bushels

import 4 million bushels

$4

$6

$8

$10

$12

$14

$16

$18

$20

Page 176If the United States and Kazakhstan entered into free trade with only one another, what would be the price of flaxseed, and what quantity of flaxseed would be traded?

For each of the following four constituent groups, determine whether free trade between the United States and Kazakhstan would help or harm the members of that group. Calculate the change in consumer or producer surplus in each country as necessary to support your claim.

The buyers of flaxseed in Kazakhstan

The sellers of flaxseed in Kazakhstan

The buyers of flaxseed in the United States

The sellers of flaxseed in the United States

Suppose the sellers of flaxseed in the importing country successfully lobby for protection in the form of a $4 tariff per bushel of flaxseed. Describe the impact of this tariff on flaxseed trade and on the consumer and producer surpluses you calculated in part d. How much deadweight loss does this tariff generate?

WORK IT OUT

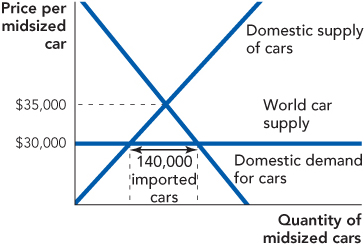

According to Chinese government statistics, China imported over 1 million cars in 2012. Let’s see what would happen to consumer and producer surplus if China were to ban car imports. To keep things simple, let’s assume that if car imports were banned, the equilibrium price of cars (holding quality constant!) would rise by $5,000.

In the figure, shade the area that represents the total gains when car imports are allowed into China.

Once China bans the import of cars, what is the dollar value of the lost gains from trade? (Hint: The chapter provides the formula.)

If car imports are banned, Chinese car producers will be better off and Chinese car consumers will be worse off. A polygon in the figure shows the surplus that will shift from consumers to producers. Write the word “Transfer” in this polygon. (Hint: It’s not the area you calculated in part b.)