How to Really Pick Stocks, Seriously

Ok, you probably can’t beat the market without a lot of luck on your side. But we do still have four pieces of important advice. Very important advice. If you apply this advice over the course of your life, you will probably save thousands of dollars, and if you become rich, you may save millions of dollars. (Suddenly, this textbook seems like a real bargain!) No, we don’t have a get-rich-quick formula for you, but there are a few simple mistakes you can avoid to your benefit and at no real cost, other than a bit of time and attention. Let’s go through each piece of advice in turn.

Diversify

The first secret to picking stocks is to pick lots of them! Since picking stocks doesn’t work well, the “secret” to wise investing is to invest in a large basket of stocks—to diversify. Diversification lowers the risk of your portfolio, how much your portfolio fluctuates in value over time.

By picking a lot of stocks, you limit your overall exposure to things going wrong in any particular company. When the energy company Enron went bankrupt in 2001, many Enron employees had put most of their life’s wealth in … can you guess? … Enron stock. That’s a huge mistake, whether you work at the company or not. If you put all your eggs in one basket, it is a disaster if the handle on that basket breaks. Instead, you should buy many different stocks, in many different sectors of the economy, and, yes, in many countries, too. You’ll end up with some Enrons, but you’ll also have some big winners, such as Google and Apple. And if Google and Apple have become Enrons and gone under since this book was published, well, that is just further reason why you should diversify!

Modern financial markets have made diversification easy. Mutual funds let you invest in hundreds of stocks with just one purchase. And since stock picking doesn’t work well, diversification has no downside—it reduces risk without reducing your expected return.

We are focusing on diversification across stocks but there are all kinds of risks in the world and you should diversify across as many as possible. U.S. stocks, for example, tend to fluctuate in value along with the growth rate of the U.S. economy. You can reduce this source of risk by including a large number of international firms in your portfolio. Bonds, art, housing, and human capital (your knowledge and skills) all have associated returns and risks, and for a given amount of return, you minimize your risk by diversifying across many assets.

To buy and hold is to buy stocks and then hold them for the long run, regardless of what prices do in the short run.

If you accept the efficient markets hypothesis, and you accept the value of diversification, your best trading strategy can be summed up very simply. It is called buy and hold. That’s right, buy a large bundle of stocks and just hold them. You don’t have to do anything more. You will be diversified, you will not be trying to beat the market, and you can live a peaceful, quiet life.

Some of the simplest ways to buy and hold mean that you replicate the well-known stock indexes. Just for your knowledge, here are a few of those indexes:

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (or the Dow for short) is the most famous stock price index. The Dow is composed of 30 leading American stocks, each of these counted equally, whether the company is large or small. The Dow is not a very diversified index.

The Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) is a much broader index of stocks than the Dow; as the name indicates, it consists of the prices of 500 different stocks. Unlike in the Dow, the larger companies receive greater weight in the index than the smaller companies. The S&P 500 is a better indicator of the market as a whole than the Dow.

The NASDAQ Composite Index averages the prices of all the companies traded on NASDAQ, or National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations, over 3,000 securities. The NASDAQ index contains more small stocks and high-tech stocks relative to the Dow or the S&P 500.

Notice that diversification changes our understanding of what makes a stock risky, or not risky. You might at first think that a risky stock is one whose price moves up and down a lot. Not exactly. If investors are diversified, and indeed most of them are, their risk depends on how much their portfolio moves up and down, not on how much a single stock moves up and down. A single stock might move up and down all the time but still an overall diversified portfolio won’t change in value much if some of your stocks are moving up, while others are moving down.

According to finance economists, the riskiest stocks are those that move up and down in harmony with the market. For instance, many real estate stocks are risky because they are highly cyclical. They move up a lot when times are good (and the rest of the market is high) and they move down a lot when times are bad. When a recession comes, a lot of people just can’t afford to buy a new house. In contrast, for an example of a relatively safe stock, consider Walmart, the discount outlet. When bad times come, yes, Walmart loses some business. But Walmart also gains some business because people who used to shop at Nordstrom now have less money and some of them will now shop at Walmart. In this regard, Walmart is partly protected from business downturns.4 Many health-care stocks are safe in a similar way. Even if times are bad, you’re probably not going to postpone that triple bypass operation; if you do, you won’t be around to see when times are good again. In other words, if you care about the risk of a stock, don’t just look at how the price of that stock moves. Look at how the price varies with the rest of the market. In the language of finance economists or statisticians, the riskiest stocks are those with the highest covariance with the market as a whole.

The lesson here is that if you are worried about risk, think about your portfolio as a whole, rather than obsessing over any single stock. Or let’s be more specific: If you are going to become an aerospace engineer, don’t buy a lot of stock in aerospace companies. The value of your human capital—which is worth a lot—is already tied up in that industry. Don’t make your overall portfolio riskier by putting more eggs in that basket. If anything, buy stocks that do well when aerospace does poorly. More generally, finance theorists say that the least risky assets for you are assets that are negatively correlated with your portfolio. What this means is that you should try to buy assets that rise in value when the rest of your portfolio is falling in value. Are you afraid that high energy prices will cripple the prospects for your career? Buy stock in a company that builds roads in Saudi Arabia. If oil prices stay high, the gains of that road-building company will partially offset your other losses. The lesson applies to more than stocks. If you become a dentist, you run the risk that a new technology will eliminate cavities. So try to limit your risk by diversifying your portfolio: Marry an optician or an engineer, not another dentist!

Avoid High Fees

We have some other advice for picking stocks. Avoid investments and mutual funds that have high fees or “loads,” as they are sometimes called. It simply isn’t worth it.

Let’s say for instance that you wish to invest in the S&P 500. Some funds charge management and administrative fees of 0.09% of your investment, but other funds can charge up to 2.5% per year for what is really the same thing! Table 10.1 shows some of the different options for investing in the S&P 500 and their expense ratios (in 2008), the yearly percentage of your investment that you must pay in fees to the fund’s managers.

TABLE 10.1 Don’t Pay Higher Fees for the Same Service

|

S&P Index Fund |

Expense Ratio (%) |

|---|---|

|

Vanguard 500 Index Mutual Fund Admiral Shares (VFIAX) |

0.09 |

|

Fidelity Spartan 500 Index Mutual Fund (FSMKX) |

0.10 |

|

State Street Global Advisors S&P 500 Index Fund (SVSPX) |

0.16 |

|

United Association S&P 500 Index Fund II (UAIIX) |

0.16 |

|

USAA S&P 500 Index Mutual Fund Member Shares (USSPX) |

0.18 |

|

Schwab S&P 500 Index Fund—Select Shares (SWPPX) |

0.19 |

|

Vantagepoint 500 Stock Index Mutual Fund Class II Shares (VPSKX) |

0.25 |

|

T. Rowe Price Equity Index 500 Mutual Fund (PREIX) |

0.35 |

|

California Investment S&P 500 Index Mutual Fund (SPFIX) |

0.36 |

|

MassMutual Select Indexed Equity A (MIEAX) |

0.67 |

|

MassMutual Select Indexed Equity N (MMINX) |

0.97 |

|

ProFunds Bull Svc, Inv (BLPSX) |

2.50 |

The funds with the higher fees don’t give you much of value in return. The lesson is simple: Don’t pay the higher fees!

Often when your broker calls you up to make a stock purchase, that purchase involves a relatively high fee. (Have you ever wondered why the broker is making the call?) Before buying or selling a stock in these circumstances, you should ask what the fee is to make the transaction. Understand the incentives of the person you are dealing with and that means understand that the broker usually earns more, the greater the number of transactions he or she can get you to make. Might that explain why he or she is telling you to buy or sell? Or maybe this really is a “once in a lifetime opportunity.”

Even small fees can add up to large differences in returns over time. Let’s say you are investing $10,000 over 30 years. If you invest with a firm that charges 0.10% a year in fees and the stock market gives a real return of 7% a year, then in 30 years you will have earned $74,016. If you invest in a firm that charges 1% a year, then in 30 years you will have about $57,434. The higher fees cost you $16,582 and, as we have shown, you probably got nothing for your extra fees. Small differences in growth or loss rates, when compounded over time, make for a big difference. The same is true for your portfolio.

That brings us to a corollary principle, to which we now turn.

Compound Returns Build Wealth

If one investment earns a higher rate of return each year than another investment, in the long run that makes a big difference. Imagine you buy a well diversified portfolio of stocks and every year you reinvest all of your dividends. A simple approximation, called the rule of 70, explains how long it will take for your investment to double in value given a specified rate of return.

Rule of 70: If the rate of return (annual percent increase in value including dividends) of an investment is x%, then the doubling time is 70/x years.

Table 10.2 illustrates the rule of 70 by showing how long it takes for an investment to double in value given different returns. With a return of 1%, an investment will double approximately every 70 years (70/1 = 70). If returns increase to 2%, the value of your investment will double every 35 years (70/2 = 35). Consider the impact of a 4% return. If this rate of return is sustained, then the value of an investment doubles every 17.5 years (70/4 = 17.5). In 70 years, the value doubles 4 times, reaching a level 16 times its starting value!

TABLE 10.2 Years to Double Using the Rule of 70

|

Annual Return (%) |

Years to Double |

|---|---|

|

0 |

Never |

|

1 |

70 |

|

2 |

35 |

|

3 |

23.3 |

|

4 |

17.5 |

The rule of 70 is just a mathematical approximation but it bears out the key concept that when compounded, small differences in investment returns can have a large effect. To make this more concrete, if you have a long time horizon, you probably should invest in (diversified) stocks rather than bonds.

In the long run, stocks offer higher returns than bonds. Since 1802, for example, stocks have had an average real rate of return of about 7% per year, while bonds have paid closer to 2% per year.5 Using our now familiar rule of 70, we know that money that grows at 7% a year will double in 10 years, but money that grows at 2% a year won’t double for 35 years. Alternatively, growing at 7% a year, $10,000 will return $76,122 in 30 years, but if it grows at 2% a year, the return will be only $18,113.

Stocks, however, have the potential for greater losses than do bonds because bond holders and other creditors are always paid before shareholders. You are unlikely to lose much money if you buy high-grade corporate or government bonds, but the stock market is highly volatile and it does periodically crash. Nonetheless, in American history, stocks almost always outperform bonds over any 20-year time period you care to examine, including the period of the Great Depression and World War II. Stocks are usually the better long-term investment.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that everyone should invest so heavily in stocks. In any particular year, or even over the course of a month, week, or day, stocks can go down in value quite a bit. If you are 80 years old and managing your retirement income, you probably shouldn’t invest much in stocks. If you have to send your twins to college in two years’ time, you might want some safer investments, as well. Nor does the past necessarily predict the future—just because stocks outperformed bonds in the past doesn’t mean that will continue to happen. Remember to diversify!

The No-Free-Lunch Principle, or No Return without Risk

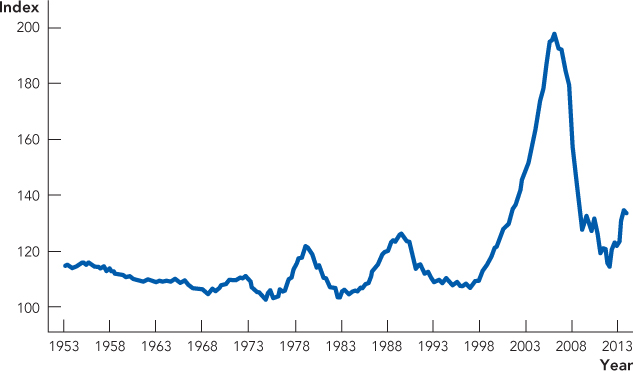

The differences between stocks and bonds, as investment vehicles, reflect a more general principle. There is a systematic tradeoff between return and risk. Figure 10.3, for example, shows the tradeoff between return and risk on four asset classes. U.S. T-bills are safe but have low returns. You can get a higher return by buying stock in a group of large firms such as in the S&P 500, but the value of those firms fluctuates a lot more than the value of T-bills, so to get the higher return, you need to bear higher risk.*

FIGURE 10.3

Note: Ibbotson Associates. 2007. Returns and Standard Deviations on the Arithmetic Averages of Nominal Returns, 1926–2006. Classic Yearbook.

The risk-return tradeoff means higher returns come at the price of higher risk.

If you want even more risk than an investment in the stock market, numerous schemes give you a chance of making a killing. The simplest of such strategies is to take all your money, fly to Las Vegas, and bet on “black” for a spin of the roulette wheel. Yes, there is a 47.37% chance that you double your wealth. That’s a high return, sort of. Sadly, there is also a 52.63% chance that you will lose everything you have, including your credit rating and the trust of your spouse and children. That’s what we call high risk.

Remember this story when you hear about a high-flying “hedge fund” or other fancy investment device. It’s easy to generate high returns for a few years by getting lucky and doubling down (betting all your winnings again). Take a look again at Figure 10.3. Higher returns come at the expense of higher risk.

This no-free-lunch principle can help you evaluate some other investments, as well. Let’s say you come into a tidy sum of money and you start wondering whether you should invest in art. Overall, should you expect art to be a better or inferior financial investment, compared with the market as a whole?

A lot of people—probably most people—buy art because they want to look at it. They enjoy hanging it on their walls. In the language of economics, art yields “a nonmonetary return,” which is just our way of saying it is fun to look at. Now suppose that investments in art earned just as high a return as investments in stocks. In that case, art would be fun to have on the wall and would be an excellent investment. But wait, that sounds like a free lunch doesn’t it? So what does the no-free-lunch principle predict?

We know that the expected returns on different assets, adjusted for risk, should be equal. So if some asset yields a higher “fun” return, those assets should, on average, yield a lower financial return. And that is exactly what we find with art. On average, art underperforms the stock market by a few percentage points a year. You can think of the lower returns as the price of having some beautiful art on your wall. Again, it’s the no-free-lunch principle in action.

This kind of analysis applies not just to art but also to real estate. Let’s say you want to buy a home. Can you expect superior or inferior financial returns over time? This question is a little trickier than the art question because two different and opposing forces operate. Let’s look at each in turn.

First, a home tends to be a risky asset for most purchasers. Let’s say you buy a $300,000 home by putting down $200,000 and borrowing the remainder. That home is probably a fairly big chunk of your overall wealth and it puts you in a relatively nondiversified position. That’s risk, people don’t usually like risk, and as we saw above, riskier assets earn, all other things equal, higher expected returns (the risk-return tradeoff).

Second, and probably more important, if you buy a house, you get to live in it. The house, like the painting, provides you with personal services and in this case those services are valuable. Many people enjoy their backyard and the feeling of owning a home and being able to paint the walls any color they want. These nonmonetary returns mean that houses can be expected to pay a relatively low financial return.

Indeed, if we look at the financial returns on real estate over a long time horizon, it turns out they are fairly low. In fact, for long periods of time, the average financial rate of return on real estate is not much different from zero. One lesson is that houses must be lots of fun!

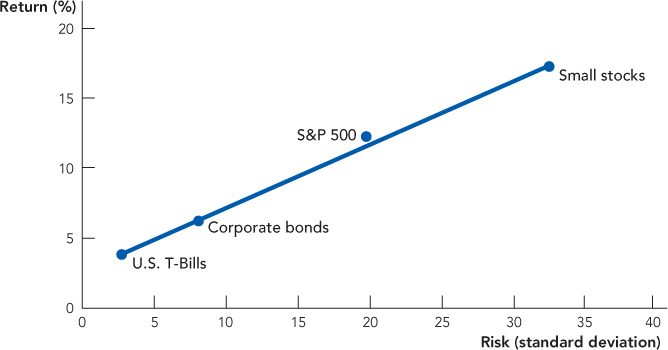

If you want to see that the downside of real estate investments is not just a recent phenomenon, take a look at Figure 10.4.

In the 50 years from 1947 to 1997, real housing prices hardly changed at all with some blips upward in the late 1970s and late 1980s. Beginning in 1997, a housing boom pushed prices well above any before seen in U.S. history. As you probably know, however, since 2006 prices have tumbled and may be even lower by the time you read this book.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 10.2

How does investing in stocks of other countries help to diversify your investments?

How does investing in stocks of other countries help to diversify your investments?

Question 10.3

Many people dream of owning a football or baseball team. Would you expect the return on these assets to be relatively high or low?

Many people dream of owning a football or baseball team. Would you expect the return on these assets to be relatively high or low?

The lesson is that most of the time a house is a good place to live but not a good place to invest. When prices started to rise in 1997 and kept rising year after year, many people thought that real estate was the investment of the century—“they ain’t making any more,” people said. But the no-free-lunch principle tells us that precisely because houses are a good place to live, we should not also expect them to be a good investment. All other things equal, fun activities yield lower financial returns than nonfun activities.

When prices rose, some people got lucky and made a killing, but other people tried to do the same and ended up bankrupt. So don’t expect to make a killing in the real estate market, and remember to diversify! One more point. Are you one of these people who doesn’t like to mow the lawn? Do you dread the notion of choosing homeowner’s insurance or worrying about when your roof will fall in? The lesson is simple: Don’t buy a house, you won’t have fun, and the financial returns won’t make it worth your while.

FIGURE 10.4