Defining Unemployment

Unemployed workers are adults who do not have a job but who are looking for work.

Is a 6-year-old without a job unemployed? Is someone in prison unemployed? What about a retired 60-year-old? In all cases the answer is no. We count someone as unemployed only if he or she is willing and able to work but cannot find a job. In practice, this means that to be counted as unemployed, a person must be an adult (16 years or older), not institutionalized (e.g., not in prison), a civilian, and, most important, that person must be looking for work. Similarly, to be counted as employed, a person must be an adult, noninstitutionalized civilian with a job.

In April, 2014, there were 9.8 million unemployed persons in the United States and 145.7 million employed persons. Together, the employed and the unemployed make up the labor force of 155.5 million (9.8 + 145.7).

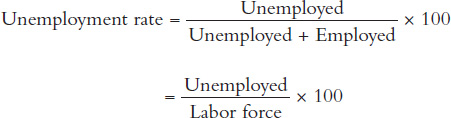

The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force without a job.

The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force without a job:

Thus, in April 2014, the unemployment rate was 6.3%:

The labor force participation rate is the percentage of adults in the labor force.

Once we have examined the issue of unemployment, we will investigate some of the determinants of the labor force participation rate, the percentage of the adult, civilian, noninstitutionalized population (adults for short) in the labor force.

How Good an Indicator Is the Unemployment Rate?

We are interested in the unemployment rate because unemployment, especially long-term unemployment, can be financially and psychologically devastating. Unemployment also means that the economy is underperforming—labor that could be used to produce valuable goods and services is being wasted. The unemployment rate is the single best indicator of how well the labor market is working in both of these senses, but it is an incomplete indicator.

Discouraged workers are workers who have given up looking for work but who would still like a job.

Individuals without a job are not counted as unemployed if they are not actively looking for work. But some people who are unemployed for a long period of time may get discouraged and stop looking for work even though they want a job. It’s difficult to know exactly how many discouraged workers there are because the concept is not well-defined. Many people who are happily retired would take a job if the wage were high enough, but should every retired person count as a discouraged worker? The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) keeps statistics on one definition of discouraged workers, which it defines as workers who want and are available for work, and who have looked for a job sometime in the last year but not in the last month because they believe that no jobs were available for them.

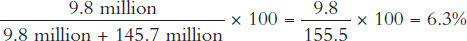

Using this definition, the number of discouraged workers in the United States is small relative to the number of unemployed workers, so counting discouraged workers as unemployed increases the unemployment rate only modestly. The number of discouraged workers has increased since the recession in 2009, but as Figure 11.2 illustrates, the unemployment rate with and without discouraged workers is similar and the two rates track each other closely.

FIGURE 11.2

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The unemployment rate also doesn’t measure the quality of the jobs people take or how well workers are matched to their jobs. A taxi driver with a PhD in chemistry, for example, is counted as fully employed by the BLS. Similarly, a worker who has a part-time job but who wants a full-time job is counted as fully employed. If we counted these workers as partially unemployed, the unemployment rate would be higher, but defining and measuring partial employment isn’t easy. If a taxi driver has a BA in English, should that be counted as almost fully employed? Nearly everyone wants a better job in some dimension (more hours, fewer hours, closer to home, higher wages, better benefits, etc.) so is everyone less than fully employed?

Underemployment rate A Bureau of Labor Statistics measure that includes part-time workers who would rather have a full-time position and people who would like to work but have given up looking for a job.

Even though any definition is imperfect, the BLS also looks at one measure of the underemployment rate. This includes part-time workers who would rather have a full-time position and also people who would like to work but have given up looking for a job. As of March 2014, this rate was 12.7 in the American economy, an unusually high level due to the slowness of labor markets to recover from the financial crisis and ensuing recession.

Given these imperfections in the official unemployment rate, economists also look at other measures of labor underutilization and indicators of how well the labor market is performing, such as the labor force participation rate, the number of full-time jobs, and average wages. Fortunately, most of these other indicators (and probably many other job characteristics that are more difficult to measure) correlate well with the unemployment rate so the unemployment rate is a good summary indicator of the state of the labor market. (See Thinking and Problem Solving question 11 for more on this.)

Economists distinguish three types of unemployment: frictional, structural, and cyclical. We start with frictional.