Frictional Unemployment

Frictional unemployment is short-term unemployment caused by the ordinary difficulties of matching employee to employer.

What is the fastest way to sell a house? Lower the price! At a low enough price, any house will sell quickly. So selling houses is easy: It’s finding a price that the seller is willing to accept and the buyer is willing to pay that is difficult. In the same way, it’s always easy to find a job if you are willing to work for peanuts. Finding a job that you want at a wage that you will accept and the employer will pay, however, takes time and effort. The difficulty of matching employees to employers creates friction in the labor market, and the resulting temporary unemployment is called frictional unemployment. Thus, frictional unemployment is short-term unemployment caused by the ordinary difficulties of matching employee to employer.

Scarcity of information is one of the causes of frictional unemployment. Workers do not know all of the job opportunities available to them and employers do not know all the available candidates and their respective qualifications. The Internet has probably lowered the underlying rate of frictional unemployment by making it easier for workers to search for jobs and for firms to search for workers.

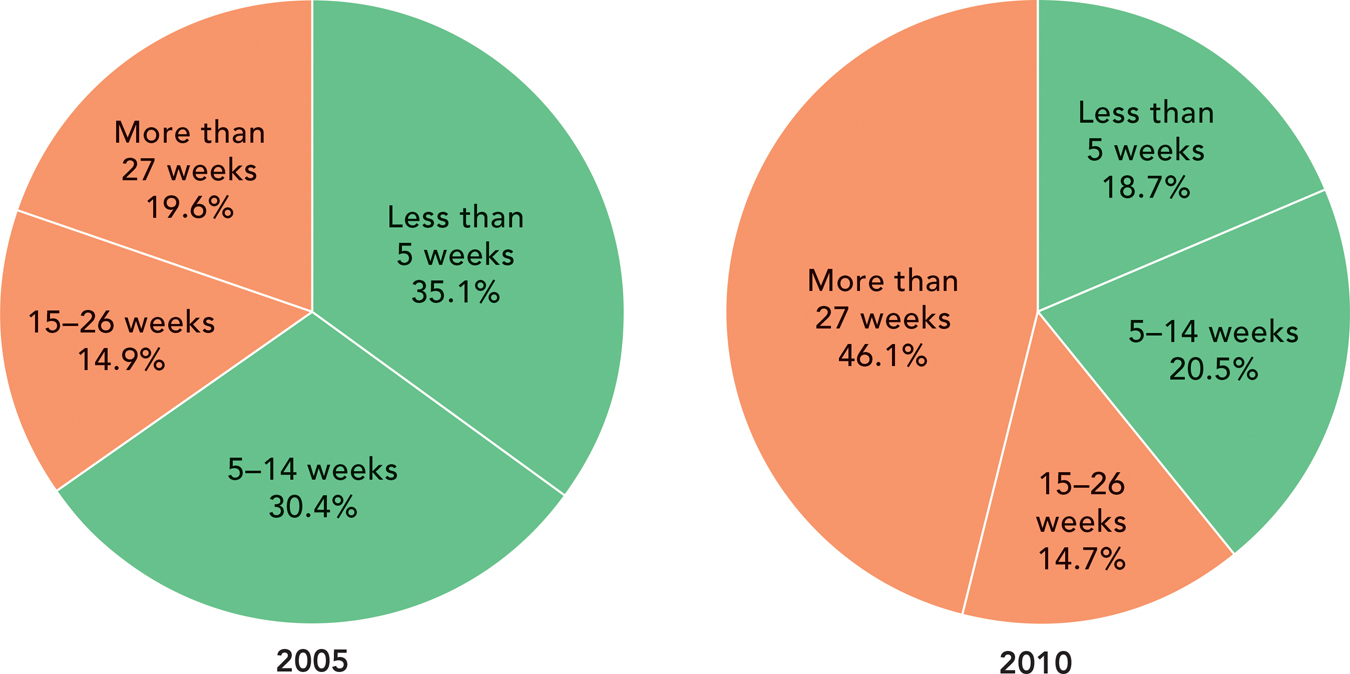

Frictional unemployment usually doesn’t last very long. If the economy is not in a recession, it might take a few weeks to find a new job, or for specialized workers perhaps a few months but not much longer. Figure 11.3 shows the typical duration of unemployment in 2005, a nonrecession year, and also in 2010 as the economy slowly exited the 2007-2009 recession. In 2005, most unemployment was of fairly short duration: 35.1% of the unemployed were jobless for less than five weeks and 30.4% were jobless for only 5 to 14 weeks. The remaining one-third were jobless for more than 14 weeks, with 19.6% jobless for more than half a year. In the United States in a nonrecession year, a significant fraction of unemployment is frictional.

FIGURE 11.3

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. Data for 2010 are as of May 2010.

The situation was very different in 2010 when a majority of the unemployed had been unemployed for more than 14 weeks. Indeed in mid-2010, 46.1% of the unemployed had been unemployed for more than 6 months. Not since the Great Depression had so many unemployed workers been unemployed for such an extended period of time.

Traditionally, long-term unemployment has been a much bigger problem in Europe than in the United States. The extraordinary increase in long-term unemployment in the United States is one of the most worrying aspects of the 2007-2009 recession. In March 2014, there were still 3.5 million people, 38.4% of the total unemployed population, who had been unemployed for more than 27 weeks. We will discuss long-term unemployment later in the chapter.

Frictional unemployment is typically a large share of total unemployment because the U.S. economy is dynamic. Innovation and the relentless pressure of competition drive progress. Progress, however, is not simply creating new jobs and adding them to the old. Rather it’s about creating new jobs and destroying old jobs. Webmasters are in; travel agents are out. We can see this process in more detail by looking at statistics on job creation and destruction.

The U.S. economy had around 210 thousand more jobs at the end of February of 2014 than it had at the beginning. This figure, however, hides an underlying reality of much greater change. In that same month, 4.59 million new jobs were created but during the same month there were also 4.38 million job separations (quits, layoffs, and other separations). The net figure, the one often reported in the news, is the difference between hires and separations (4.59 - 4.38 = 0.21 million, or 210,000 new jobs). These figures are typical. In any given month, millions of jobs are created and millions of jobs are destroyed. “Creative destruction,” a term coined by economist Joseph Schumpeter, describes this process well.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 11.1

What is a key cause of frictional unemployment?

What is a key cause of frictional unemployment?

Question 11.2

To minimize frictional unemployment, unemployed workers would have to accept the first job they were offered no matter what the wage. Is frictional unemployment always a bad thing?

To minimize frictional unemployment, unemployed workers would have to accept the first job they were offered no matter what the wage. Is frictional unemployment always a bad thing?

Creative destruction occurs at the level of the firm and the industry. Even in an industry with constant or increasing employment, the location of employment changes as uncompetitive firms disappear or shrink and new firms grow. Kmart filed for bankruptcy in 2002 and laid off 34,000 workers, but in that same year its more productive rival, Walmart, hired 139,000 workers.1

Creative destruction also occurs at the level of the industry. During the 1970s, for example, the real price of oil increased from about $10 a barrel to nearly $80 a barrel (see Chapter 4, Figure 4.9). The oil shocks required a fundamental reallocation of labor from industries that were heavily dependent on oil to industries less dependent on oil. But it takes more time (and thus more unemployment) for workers to move from one industry to another industry than to move from one firm to another firm in the same industry—this type of unemployment that occurs in response to deep changes in the economy is called structural unemployment, the topic of the next section.