The Costs of Inflation

To the person in the street, the costs of inflation are obvious—prices are going up; what could be worse? But most people rarely consider that inflation also raises their wages. (No doubt, we all have a tendency to think that bad events, like price increases, are the fault of others but good events, like higher wages, are due to our own virtues.) If all prices including wages are going up, then what is the problem with inflation?

If everyone knew whether the rate of inflation was 2% or 8%, then everyone could prepare and the exact inflation rate would not matter very much. But instead of everyone knowing the rate, it’s more often the case that no one knows the rate of inflation! In the United States, inflation was 1.3% in 1964; the rate more than quadrupled to 5.7% in 1970 and increased to 11% per year by 1974. Inflation caught most people by surprise. And when inflation decreased from 13% in 1980 to 3% in 1983, most people were surprised again. Inflation also tends to be more variable and thus more difficult to predict when the inflation rate is high. Take a look again at the right panel of Figure 12.4. Inflation in Peru went from 77% in 1986 to 7,500% in 1990 and then back down to 73% in 1992. Who can predict such changes?

High rates of inflation do create some problems, as we will explain, but volatile or uncertain inflation is even more costly. We now cover some specific problems or costs introduced by high and volatile inflation. Keep in mind the picture of inflation as a kind of insidious, slow moving cancer. Inflation destroys the ability of market prices to send signals about the value of resources and opportunities.

Price Confusion and Money Illusion

Prices are signals and inflation makes price signals more difficult to interpret. In our inflation parable, for example, the baker initially thought that the increase in the demand for bread signaled that the real demand for bread had increased. In fact, since all prices were rising, the real demand for bread had not increased. Confusing a nominal signal with a real signal has real consequences. The baker thought that prices were telling him to work harder and produce more bread. When he later discovered that all prices had risen, he knew that he had made a costly mistake.

Now imagine that one day the real demand for bread does increase, only now the baker is so used to inflation, he ignores the signal. Instead of working harder, the baker continues to bake the same number of loaves of bread as before. Opportunities are missed because signals have become obscured.

In a modern economy, it might seem easy enough to figure out whether an increase in demand for bread reflects a real increase in demand or just an increase in the money supply. Just pick up the Wall Street Journal and read the articles about monetary policy. But it’s not actually so easy. Sometimes the money supply is increasing and the real demand for bread is going up, both at the same time. It is difficult to sort out the relative strength of both influences. Or perhaps the baker never understood the principles of economics, or, unlike you (!), never read a really good economics textbook.

Money illusion is when people mistake changes in nominal prices for changes in real prices.

Human beings are not always perfectly rational, which makes reading signals even more difficult. Even when we should know better, we sometimes treat the higher wages and prices that result from inflation as higher wages and prices in real terms. If the price of a movie goes up 10% and other prices including wages go up by about the same amount, we ought to conclude that the real price of a movie has stayed more or less the same. But many people conclude, mistakenly, that movies have become “more expensive.” They treat this as a change in relative price: They may see fewer movies or make other decisions based on this new price. Economists call this “money illusion.” Money illusion is when people mistake changes in nominal prices for changes in real prices.

In short, inflation usually confuses consumers, workers, firms, and entrepreneurs. When price signals are difficult to interpret, the market economy doesn’t work as well—resources are wasted in activities that appear profitable but in fact are not, entrepreneurs are less quick to respond to real opportunities, and resources flow more slowly to profitable uses.

Inflation Redistributes Wealth

In our inflation parable, the government bought bread, shirts, and woodwork simply by printing paper. Where did these real goods come from? They came from the baker, tailor, and carpenter. Inflation transfers real resources from citizens to the government. Thus, inflation is a type of tax.

The inflation tax does not require tax collectors, a tax bureaucracy, or extensive record keeping. You can hide from most taxes by keeping your transactions secret and saving your money under the bed. But you can’t hide from the inflation tax! Money under the bed is precisely what inflation does tax because as prices rise, the value of the dollars under the bed falls. It’s not surprising, therefore, that money-strapped governments in danger of collapsing typically use massive inflation. Almost all the hyperinflations in Table 12.2 involved governments with massive debts or spending that could not be paid for with regular taxes.

Inflation does more than transfer wealth to the government—it also redistributes wealth among the public, especially between lenders and borrowers. To see why, suppose that a lender lends money at an interest rate of 10% but that over the course of the year the inflation rate is also 10%. On paper, the lender has earned a return of 10%—we call this the “nominal return.” But what is the lender’s real rate of return? The lender is paid 10% interest, but she is paid in dollars that have become 10% less valuable. Thus, the lender’s real rate of return is 0%.

Thus, inflation can reduce the real return that lenders receive on their loans, in effect transferring wealth from lenders to borrowers. In the 1970s, for example, high inflation rates meant the real value of 30-year fixed-rate mortgages that were taken out in the 1960s declined tremendously, redistributing billions of dollars from lenders to borrowers. Borrowers benefited but many lenders went bankrupt.

In the late 1970s, however, many people began to expect that 10% inflation was here to stay, so home buyers were willing to take out long-term mortgages with interest rates of 15% or higher. When inflation fell unexpectedly in the early 1980s, these borrowers found that their real payments were much higher than they had anticipated. Wealth was redistributed from borrowers to lenders.

We can explain the relationship between inflation and wealth redistribution more precisely by writing the relationship between the lender’s real rate of return, the nominal rate of return, and the inflation rate as follows:

Real Interest Rate = Nominal rate − Inflation rate (1)

or, in symbols,

rReal = i − π

Real rate of return is the nominal rate of return minus the inflation rate.

In words, the real rate of return is equal to the nominal rate of return minus the inflation rate.

Nominal rate of return is the rate of return that does not account for inflation.

Lenders, of course, will not lend money at a loss. Thus, when lenders expect inflation to increase, they will demand a higher nominal interest rate. For example, if lenders expect that the inflation rate will be 7% and the equilibrium real rate (determined in the market for loanable funds—see Chapter 9) is 5%, then lenders will ask for a nominal interest rate of approximately 12% (7% to break even given the expected rate of inflation plus the 5% equilibrium rate). If lenders expect that the inflation rate will be 10%, lenders will demand a nominal interest rate of approximately 15% (10% to break even given the expected rate of inflation plus the 5% equilibrium rate).

The tendency of nominal interest rates to increase with expected inflation rates is called the Fisher effect (after economist Irving Fisher, 1867–1947). As an approximation,* we can write the Fisher effect as

i = Eπ − rEquilibrium (2)

i = Nominal interest rate, Eπ = Expected inflation rate

The Fisher effect is the tendency of nominal interest rates to rise with expected inflation rates.

rEquilibrium = Equilibrium real rate of return

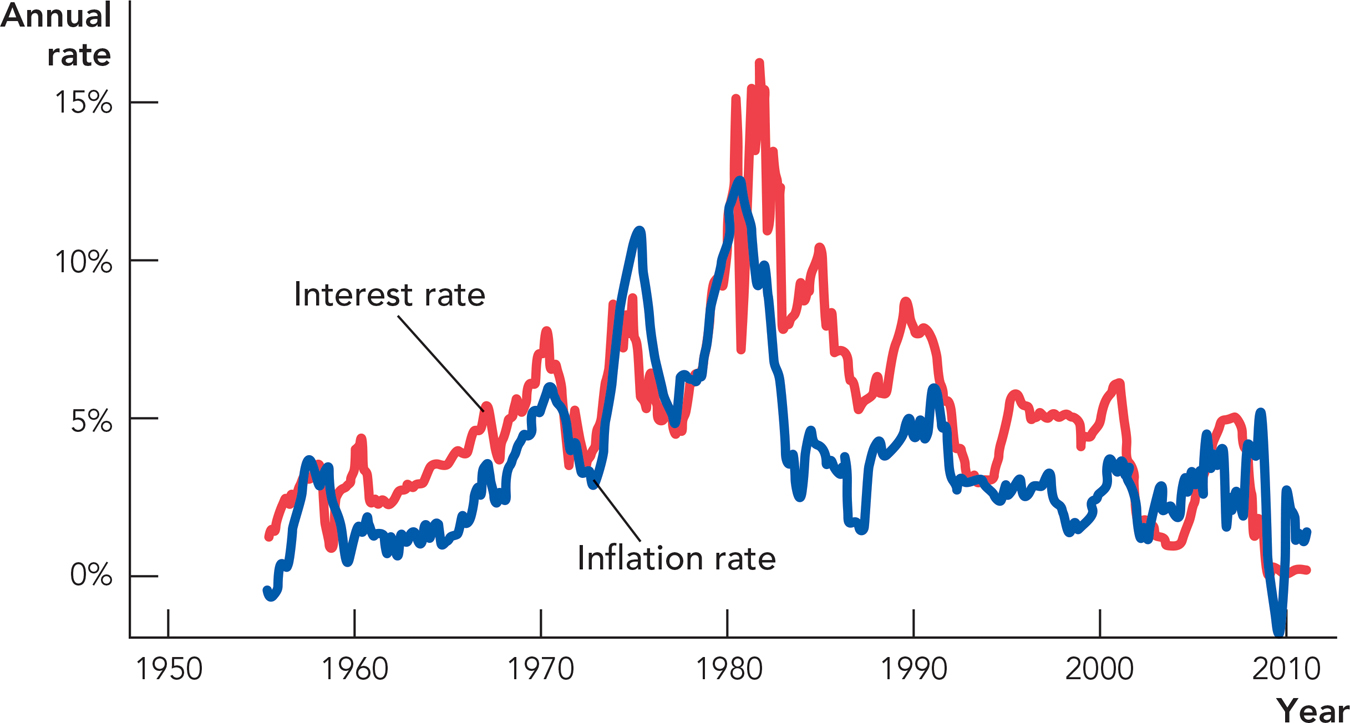

The Fisher effect says that the nominal interest rate is equal to the expected inflation rate plus the equilibrium real interest rate. Most important, the Fisher effect says that the nominal rate will rise with expected inflation. We can see the Fisher effect in Figure 12.6, which graphs the inflation rate and short-term nominal interest rate in the United States from 1955 to 2010.

FIGURE 12.6

Thus, repeating equations 1 and 2, we have

rReal = i − π (1)

and

i = Eπ + rEquilibrium (2)

If we substitute i from equation 2 into equation 1, we see that the real rate of return will be determined in large part by the difference between expected inflation and actual inflation:

rReal = (Eπ − π) + rEquilibrium

If (Eπ < π), that is, if expected inflation is less than actual inflation, then the real rate of return will be less than the equilibrium rate and will quite possibly be negative. Wealth will be redistributed from lenders to borrowers.

If (Eπ > π), that is, if expected inflation is greater than actual inflation or equivalently if there is an unexpected “disinflation,” then the real rate of return will be higher than the equilibrium rate. Wealth will be redistributed from borrowers to lenders.

Only when Eπ = π, that is, when expected inflation is equal to actual inflation, will the real return be equal to the equilibrium return. In this case, there will be no unexpected redistribution of wealth between borrowers and lenders. We summarize the effects of inflation on the redistribution of wealth in Table 12.3.

TABLE 12.3 The Redistribution of Wealth Caused by Inflation

|

Unexpected inflation (Eπ < π) |

Unexpected disinflation (Eπ > π) |

Expected inflation = Actual inflation (Eπ = π) |

|---|---|---|

|

Real rate less than equilibrium rate |

Real rate greater than equilibrium rate |

Real rate equal to equilibrium rate |

|

Harms lenders Benefits borrowers |

Benefits lenders Harms borrowers |

No redistribution of wealth |

Monetizing the debt is when the government pays off its debts by printing money.

Governments are often borrowers so governments benefit from unexpected inflation. Thus, a government with massive debts has a special incentive to increase the money supply—called monetizing the debt. Why doesn’t the government always inflate its debt away? One reason is the Fisher effect. If lenders expect that the government will inflate its debt away, they will only lend at high nominal rates of interest. To avoid this outcome, the government may try to make a credible promise to keep the inflation rate low.

Another reason the government doesn’t always inflate its debt away is that people who buy government bonds are typically voters who would be upset if their real returns were shrunk to zero or less. But what do you think would happen to inflation rates if a nation’s debt was owed to foreigners? A government would probably have a stronger incentive to inflate away debt owed to foreigners than debt owed to voters. The U.S. debt is increasingly owed to foreigners, which makes some economists predict a return of inflation in the United States, especially if a future U.S. government finds it difficult to cover its debt with other taxes (see Chapter 17 on fiscal problems in the United States).

Inflation and the Breakdown of Financial Intermediation Sometimes a government will combine inflation with controls on interest rates, making it illegal to raise the nominal rate of interest and preventing the Fisher effect from operating. When nominal interest rates are not allowed to rise and the inflation rate is high, the real rate of return will be negative. In this way, bank savings accounts are turned into wasting accounts.

When real interest rates turn negative, people take their money out of the banking system, using the cash to invest abroad (if they can), or to buy a real asset like land that is appreciating in value alongside inflation, or to simply consume more. In any of these cases, when many people pull their money out of the banking system, the supply of savings declines and financial intermediation becomes less efficient. Table 12.4 shows a number of examples of severely negative real interest rates. In every case, economic growth was also negative. Countries with negative real interest rates usually have many problems so we can’t blame all of the poor economic growth on inefficient financial intermediation. Nonetheless, studies show that even after controlling for other factors, negative real interest rates reduce financial intermediation and economic growth.

TABLE 12.4 Negative Interest Rates and Economic Growth

|

Country |

Years |

Real Interest Rate (%) |

Per Capita Growth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Argentina |

1975–1976 |

−69 |

−2.2 |

|

Bolivia |

1982–1984 |

−75 |

−5.2 |

|

Chile |

1972–1974 |

−61 |

−3.6 |

|

Ghana |

1976–1983 |

−35 |

−2.9 |

|

Peru |

1976–1984 |

−19 |

−1.4 |

|

Poland |

1981–1982 |

−33 |

−8.6 |

|

Sierra Leone |

1984–1987 |

−44 |

−1.9 |

|

Turkey |

1979–1980 |

−35 |

−3.1 |

|

Venezuela |

1987–1989 |

−24 |

−2.7 |

|

Zaire |

1976–1979 |

−34 |

−6.0 |

|

Zambia |

1985–1988 |

−24 |

−1.9 |

|

Source: Easterly, W. 2002. The Elusive Quest for Growth. Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. |

|||

Hyperinflation and the Breakdown of Financial Intermediation If inflation is moderate and stable, lenders and borrowers can probably forecast reasonably well and loans can be signed with rough certainty regarding the real value of the future payments. But when inflation is volatile and unpredictable, long-term loans become riskier and they may not be signed at all. Thus, the real problem of unexpected inflation is not simply that it redistributes wealth, but—even worse—that few long-term contracts will be signed when borrowers and lenders both fear that unexpected inflation or deflation could redistribute their wealth.

High and volatile inflation rates have decimated many developing nations. When Peru experienced hyperinflation between 1987 and 1992, private loans virtually disappeared. When firms cannot get loans, they cannot build for future expansion and growth. The price level in Peru is approximately 10 million times higher today than it was in 1997. Who could have predicted these rates of increase or built them into a contract?

The virtual elimination of inflation in Mexico shows how much capital markets can flourish in a stable environment. In the 1980s, the rate of Mexican inflation at times exceeded 100%. Long-term loans were very hard to come by. In the United States, it’s relatively easy to borrow money for 10, 20, or 30 years or even longer. But as recently as 2002, 90% of the local currency debt in Mexico matured within one year.

In the 1990s, the inflation rate in Mexico came down to about 10% and more recently it has been 3% to 5%, close to the rate in the United States. Mexican capital markets have grown rapidly as inflation has been stabilized. In 2006, the Mexican government was able to introduce a 30-year bond, denominated in Mexican pesos; this would have been unheard of as recently as the mid-1990s.

The greater ease and predictability of long-term borrowing also has caused the Mexican mortgage market to take off. It is now relatively easy to obtain a long-term mortgage in Mexico—due largely to lower and less volatile inflation—and many more middle-class Mexicans have been able to afford homes.

It’s not only lenders and borrowers that need to forecast future inflation rates. Any contract involving future payments will be affected by inflation. Workers and firms, for example, often make wage agreements several years in advance, especially when unions or other forms of collective bargaining are in place. If the rate of inflation is high and volatile, they are more likely to set wages at the wrong level. Either wages will be too high, and the firm will be reluctant to use more overtime or hire more workers, or wages will be too low, in which case workers are underpaid, they will slack off, and some will quit their jobs altogether.

Unexpected inflation redistributes wealth throughout society in arbitrary ways. When the inflation rate is high and volatile, unexpected inflation is difficult to avoid and society suffers as long-term contracting grinds to a halt.

Inflation Interacts with Other Taxes

Most tax systems define incomes, profits, and capital gains in nominal terms. In these systems, inflation, even expected inflation, will produce some tax burdens and tax liabilities that do not make economic sense.

To make this concrete, let’s say you bought a share of stock for $100, and over several years inflation alone pushed its price to $150. The U.S. tax system requires that you pay profits on the $50 gain even though the gain is illusory. Yes, you have more money in nominal terms, but that money is worth less in terms of its ability to purchase real goods and services. In real terms, the stock hasn’t increased in price at all yet you must still pay tax on the phantom gain.

In this case, inflation leads to people paying capital gain taxes when they should not. The overall tax burden rises. The long-run effect is to discourage investment in the first place.

Depending on the details of particular tax systems, inflation can also push people into higher tax brackets or make corporations pay taxes on phantom business profits. In short, inflation increases the costs associated with tax systems.

Inflation Is Painful to Stop

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 12.6

Consider unexpected inflation and unexpected disinflation. How is wealth redistributed between borrowers and lenders under each case?

Consider unexpected inflation and unexpected disinflation. How is wealth redistributed between borrowers and lenders under each case?

Question 12.7

What happens to nominal interest rates when expected inflation increases? What do we call this effect?

What happens to nominal interest rates when expected inflation increases? What do we call this effect?

Question 12.8

What does unexpected inflation do to price signals?

What does unexpected inflation do to price signals?

Once inflation starts, it’s painful to stop—this is one of the biggest costs of inflation. Imagine that the inflation rate has been 10% in an economy for some time so that loans, wage agreements, and all kinds of business contracts are based on the expectation that inflation will continue at 10%. The government can reduce inflation by reducing the growth in the money supply, but what will happen to the economy? When workers, firms, and consumers expect 10% inflation, a lower rate is a shock. At first, firms may interpret the lower rate as a reduction in real demand and thus they may reduce output and employment. Furthermore, contracts signed on the expectation of 10% inflation are now out of whack with actual inflation. Wage bargains that promised raises of 12% per year were modest when inflation was 10%, but are huge increases in real wages when the inflation rate is 3%. Workers may be thrown out of work as the unexpected increase in their real wage makes them unaffordable. Only in the long run, as expectations adjust, does the economy move to a point where both inflation and unemployment are low.

In the United States, for example, Ronald Reagan was elected to the presidency in 1980 after inflation in the United States hit 13.5% a year. By 1983, tough monetary policy had reduced the inflation rate to 3%, but the consequence was a severe recession and an unemployment rate of just over 10%. Only in 1988 did unemployment return to near 5.5%.