Shocks to the Components of Aggregate Demand

Changes in  can be broken down into changes in

can be broken down into changes in  ,

,  ,

,  , or

, or  .

.

We have already looked at how changes in  can create AD shocks so the only other shifter is changes in

can create AD shocks so the only other shifter is changes in  . We can think of changes in

. We can think of changes in  as increasing or decreasing the spending rate, holding the money supply constant. To understand why the spending rate might change, it’s useful to recall the national spending identity from Chapter 6, Y = C + I + G + NX. The national spending identity reminds us that spending is spending on something. For example, if

as increasing or decreasing the spending rate, holding the money supply constant. To understand why the spending rate might change, it’s useful to recall the national spending identity from Chapter 6, Y = C + I + G + NX. The national spending identity reminds us that spending is spending on something. For example, if  increases, that means the growth rate of C, I, G, or NX must increase— that is, an increase in

increases, that means the growth rate of C, I, G, or NX must increase— that is, an increase in  must be apportioned among an increase in

must be apportioned among an increase in  ,

,  ,

,  , or

, or  .

.

It’s often easier to think about changes in  working through changes in

working through changes in  ,

,  ,

,  , or

, or  because each of these factors has somewhat different causes and consequences. Let’s look at a change in

because each of these factors has somewhat different causes and consequences. Let’s look at a change in  . Why might

. Why might  decrease?

decrease?

A Shock to

Fear can cause  to decrease. Imagine that consumers suddenly become more pessimistic and fearful about the economy, as they did in 2008 when the banking system was in danger of collapse. The “animal spirits,” to use the famous phrase of John Maynard Keynes, turn negative. Workers, for example, might be worried about becoming unemployed, so they decide to postpone buying a new car or remodeling their kitchen. The decrease in consumption purchases will temporarily reduce spending growth,

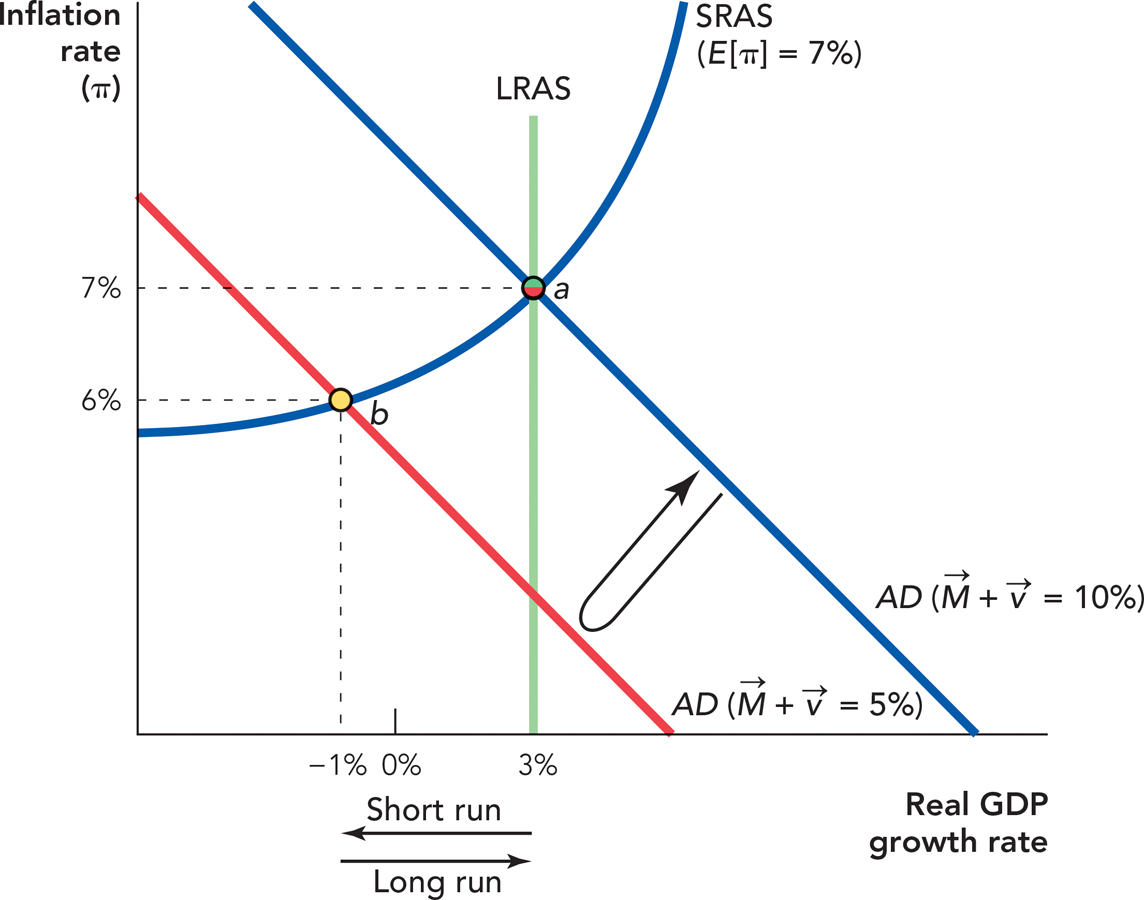

to decrease. Imagine that consumers suddenly become more pessimistic and fearful about the economy, as they did in 2008 when the banking system was in danger of collapse. The “animal spirits,” to use the famous phrase of John Maynard Keynes, turn negative. Workers, for example, might be worried about becoming unemployed, so they decide to postpone buying a new car or remodeling their kitchen. The decrease in consumption purchases will temporarily reduce spending growth,  . A decrease in spending growth, a negative AD shock, shifts the AD curve inward, reducing the real growth rate in the short run. Figure 13.15 illustrates this scenario. We begin at point a with an inflation rate of 7%, an expected inflation rate of 7%, and a real growth rate of 3%. A decrease in spending growth shifts the AD curve inward and to the left. With lower spending growth, wage growth should fall to match the reduction in price growth, but because wages are sticky, especially in the downward direction, wage growth remains high so firms are unprofitable, employment falls, and the economy slows.

. A decrease in spending growth, a negative AD shock, shifts the AD curve inward, reducing the real growth rate in the short run. Figure 13.15 illustrates this scenario. We begin at point a with an inflation rate of 7%, an expected inflation rate of 7%, and a real growth rate of 3%. A decrease in spending growth shifts the AD curve inward and to the left. With lower spending growth, wage growth should fall to match the reduction in price growth, but because wages are sticky, especially in the downward direction, wage growth remains high so firms are unprofitable, employment falls, and the economy slows.

FIGURE 13.15

declines so the AD curve shifts inward. In the short run, wages are sticky so although spending growth declines, wage growth does not. As a result, real growth falls to −1% and the inflation rate falls to 6% at point b. In the long run as fear recedes and wages become unstuck,

declines so the AD curve shifts inward. In the short run, wages are sticky so although spending growth declines, wage growth does not. As a result, real growth falls to −1% and the inflation rate falls to 6% at point b. In the long run as fear recedes and wages become unstuck,  returns to its normal rate, as does real growth.

returns to its normal rate, as does real growth.Thus, in the short run, the economy moves from point a to point b, where the inflation rate is lower and the real growth rate is also lower—in this example at point b, growth is negative and the economy is in a recession.

In the long run, fear recedes, wages adjust, and the spending growth rate returns to normal so the economy returns to long-run equilibrium at point a. Let’s explain the shift back of the AD curve in the long run in greater detail.

Why Changes in  Tend to Be Temporary

Tend to Be Temporary

Changes in  (i.e., changes in the growth rate of C, I, G, or NX) differ from changes in

(i.e., changes in the growth rate of C, I, G, or NX) differ from changes in  in one respect.

in one respect.  can be permanently set at any rate—5%, 17%, 103%—but changes in

can be permanently set at any rate—5%, 17%, 103%—but changes in  tend to be temporary. How do we know this? Recall that in our example consumers were worried about becoming unemployed, so they cut back on purchases like buying a new automobile, that is, a decrease in

tend to be temporary. How do we know this? Recall that in our example consumers were worried about becoming unemployed, so they cut back on purchases like buying a new automobile, that is, a decrease in  in this period. In the next period, consumers might cut back on some other purchase, but as they cut back, the consumption that remains becomes even more important (like groceries and rent) and consumers stop cutting back. Also, as consumers cut back on consumption, their savings increase and they become more reassured about spending. Thus, if nothing else changes, consumption will return to its normal growth rate.

in this period. In the next period, consumers might cut back on some other purchase, but as they cut back, the consumption that remains becomes even more important (like groceries and rent) and consumers stop cutting back. Also, as consumers cut back on consumption, their savings increase and they become more reassured about spending. Thus, if nothing else changes, consumption will return to its normal growth rate.

As another example, consider an increase in government spending to stimulate the economy (fiscal policy, which we will discuss in Chapter 18). An increase in spending will temporarily increase  , shifting the AD curve out. The government can do this in the short run, but if

, shifting the AD curve out. The government can do this in the short run, but if  were to grow at an unusually high rate year after year, government purchases would soon dominate the economy. In fact, even if voters did not object, eventually

were to grow at an unusually high rate year after year, government purchases would soon dominate the economy. In fact, even if voters did not object, eventually  would have to fall because in the long run, government spending cannot grow faster than the rate of economic growth (otherwise, government spending would eventually be more than GDP, and that is not possible). The analysis is similar for the other components of Y because as we know from Chapter 6, the shares of GDP devoted to C, I, G, and NX have been quite stable over time, so changes in

would have to fall because in the long run, government spending cannot grow faster than the rate of economic growth (otherwise, government spending would eventually be more than GDP, and that is not possible). The analysis is similar for the other components of Y because as we know from Chapter 6, the shares of GDP devoted to C, I, G, and NX have been quite stable over time, so changes in  ,

,  ,

,  , or

, or  tend to be temporary.

tend to be temporary.

Thus, returning to Figure 13.15, we show that a decrease in  reduces AD and the rate of inflation in this period. In future periods, however,

reduces AD and the rate of inflation in this period. In future periods, however,  will return to its normal rate and, as it does, AD and inflation will return to their previous rates. Notice that because the AD curve shifts back in the long run, changes in

will return to its normal rate and, as it does, AD and inflation will return to their previous rates. Notice that because the AD curve shifts back in the long run, changes in  ,

,  ,

,  , or

, or  do not change the rate of inflation in the long run. In other words, long-run or sustained inflation requires ongoing increases in the money supply, a truth we’ve already outlined in Chapter 12.

do not change the rate of inflation in the long run. In other words, long-run or sustained inflation requires ongoing increases in the money supply, a truth we’ve already outlined in Chapter 12.

Other AD Shocks

We have already said that fear could decrease consumption spending (and, thus, confidence could increase consumption spending). What other factors could change  ,

,  ,

,  , or

, or  ?

?

Fear and confidence play a similar role in investment spending as in consumption spending. If business people fear that the economy is entering a recession, they may want to wait to make large investments in a new plant and equipment. Similarly, confidence about the future will encourage business people to make significant investments.

Wealth shocks can also increase or decrease AD. Imagine, for example, that the stock market or the housing market tumbles. Before the fall in prices, consumers might have spent freely, expecting that in their retirement years or in an emergency they could sell their stocks or their homes and live on the proceeds. When prices fall, consumers suddenly realize that their wealth has fallen so they need to save more; thus, they cut back on their spending. In 2008, for example, a simultaneous fall in stock and housing prices caused a very large decrease in consumption spending. (A positive wealth shock works the opposite way. As the stock market rises, for example, consumers spend more today as their increasing wealth gives them confidence that they will have plenty in the future.)

Taxes are another important shifter of  and

and  . An increase in taxes can reduce consumption growth and a decrease in taxes can increase consumption growth. Taxes targeted at investment spending—such as an investment tax credit—can have a similar effect on investment growth. Changes in taxes are also a part of fiscal policy to be studied in Chapter 18.

. An increase in taxes can reduce consumption growth and a decrease in taxes can increase consumption growth. Taxes targeted at investment spending—such as an investment tax credit—can have a similar effect on investment growth. Changes in taxes are also a part of fiscal policy to be studied in Chapter 18.

Big increases in the growth rate of government spending will increase AD, and decreases in the growth rate of government spending will reduce AD. During a war, for example, government spending usually increases at a high rate, thereby shifting the AD curve outward. Government spending can also be timed to try to offset the business cycle (fiscal policy again—see Chapter 18).

The category called net exports consists of exports minus imports. We look at exports and imports more closely in Chapter 19 and Chapter 20, but for now the basic idea is simple. If other countries increase their spending on our goods (exports), that increases our AD. If we shift our spending away from domestic goods to foreign goods (imports), that reduces our AD. Table 13.2 summarizes some of the factors that can shift the AD curve.

Let’s now apply the insights from the AD/AS model to understanding the so-called Great Depression, a watershed event in U.S. history.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 13.8

What always happens to unexpected inflation in the long run?

What always happens to unexpected inflation in the long run?

Question 13.9

Show what happens to the aggregate demand curve if consumers fear a recession is coming and cut back on their expenditures.

Show what happens to the aggregate demand curve if consumers fear a recession is coming and cut back on their expenditures.

TABLE 13.2 Some Factors That Shift the Aggregate Demand Curve

|

Positive Shocks (Increase AD) (= Higher Growth Rate of Spending) |

Negative Shocks (Decrease AD) (= Lower Growth Rate of Spending) |

|---|---|

|

A faster money growth rate |

A slower money growth rate |

|

Confidence |

Fear |

|

Increased wealth |

Reduced wealth |

|

Lower taxes |

Higher taxes |

|

Greater growth of government spending |

Lower growth of government spending |

|

Increased export growth |

Decreased export growth |

|

Decreased import growth |

Increased import growth |