The U.S. Money Supplies

Money is a widely accepted means of payment.

Just about everyone expects to be paid in money. If you show up with money—at least in its appropriate form—hardly anyone will turn you away. In other words, money is a widely accepted means of payment.

But money is more than cash. Cash, or currency, is paper bills and coins, which serve as a quick and efficient way of making small transactions. But currency is not so useful for larger transactions, especially between businesses. Often it is easier to pay by check or debit card (which can be thought of as an electronic check) or by credit card (and then pay your bill later by check). For larger purchases, you might transfer money from a savings account to a checking account and then pay by check or debit. All these means of payment are money but they are not currency.

The most important assets that serve as means of payment in the United States today are:

Currency—paper bills and coins.

Total reserves held by banks at the Fed.

Checkable deposits—your checking or debit account.

Savings deposits, money market mutual funds, and small-time deposits.

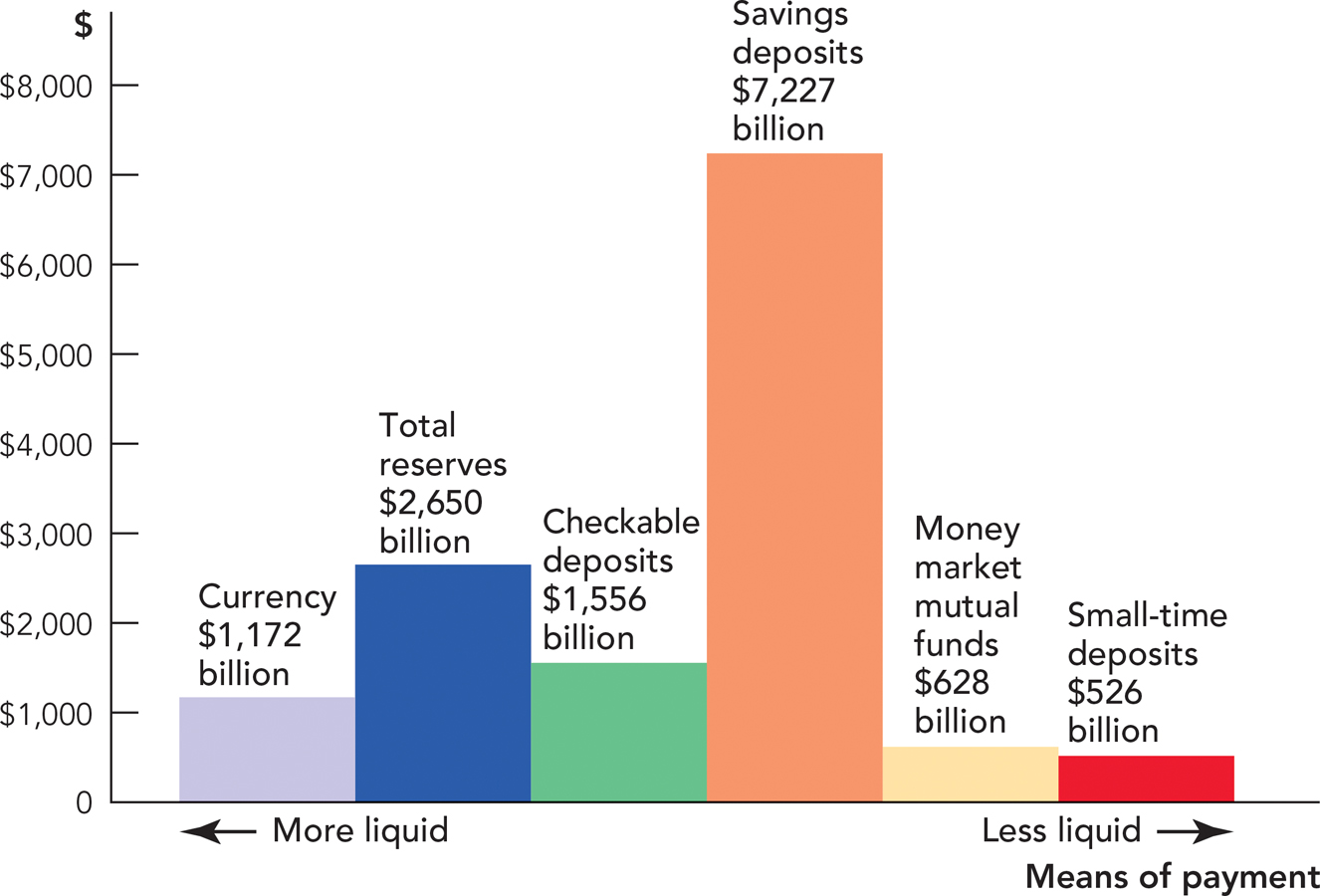

Figure 15.1 shows the magnitude and proportions of the major means of payment in the United States (there are also some smaller items, such as traveler’s checks, that we have omitted).

FIGURE 15.1

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Let’s say a few words about each of these means of payment. Currency is coins and paper bills (Federal Reserve Notes) held by people and nonbank firms. If you look at the total for currency (almost $1.2 trillion) and divide it by the American population (about 300 million, rounding down), that amounts to about $4,000 per person (and even more per adult). Who has this much cash on hand? Of course, some of the money is in cash registers and some drug dealers do hold a lot of cash, but the real explanation for why so much U.S. cash exists is that quite a bit is used in other countries. Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador all use the U.S. dollar as their official currency, as do some other small nations like the Turks and Caicos Islands. Dollars are also used unofficially in many other unstable countries as a means of preserving and protecting wealth. When Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was captured, he had $750,000 in U.S. hundred dollar bills in his hideaway.

“Total reserves” held by banks at the Fed is the means of payment you probably don’t have personal experience with, but total reserves play a very important role in the financial system. All major banks have accounts at the Federal Reserve System—accounts that they use for trading with other major banks and for dealings with the Fed itself. It’s not currency in these accounts but electronic claims that can be converted into currency if the bank wishes.

Checkable deposits are just like they sound, namely deposits that you can write checks on or can access with a debit card. These are the sorts of deposits we use most often in making daily transactions. Often these are also called demand deposits because you can access this money “on demand.”

The largest means of payment are savings accounts, money market mutual funds, and small-time deposits (also called certificates of deposit or CDs). Each of these components can be used to pay for goods and services, but typically with a little bit of extra work or trouble. Payments from a savings account can be made, for example, by first transferring the money to a checkable account. A money market mutual fund is a mutual fund invested in relatively safe short-term debt and government securities. Money market mutual funds typically allow you to write some number of checks per year or you can always sell part of your fund and transfer the money to a checkable account. Small-time deposits cannot be withdrawn without penalty before a certain time period has elapsed, usually six months or a year.

A liquid asset is an asset that can be used for payments or, quickly and without loss of value, be converted into an asset that can be used for payments.

A liquid asset is an asset that can be used for payments or, quickly and without loss of value, be converted into an asset that can be used for payments. The more liquid the asset, the more it can serve as money. Currency is usually the most liquid asset since currency can be spent almost everywhere. Checkable deposits and reserves are also very liquid, since they can also be spent easily and they can be turned into currency without loss. Money market mutual funds and time deposits are less liquid since sometimes it takes time and a little bit of trouble to turn these assets into currency or checkable deposits. It’s possible to use even less liquid assets as a means of payment (we will take your house in return for, say, a copy of this textbook), but it is inconvenient. Economists therefore have found that these components are the most useful for analyzing the effect of “money” on the economy. It should be clear, however, that the money supply can be defined in different ways depending on exactly which kinds of liquid assets are included in the definition.

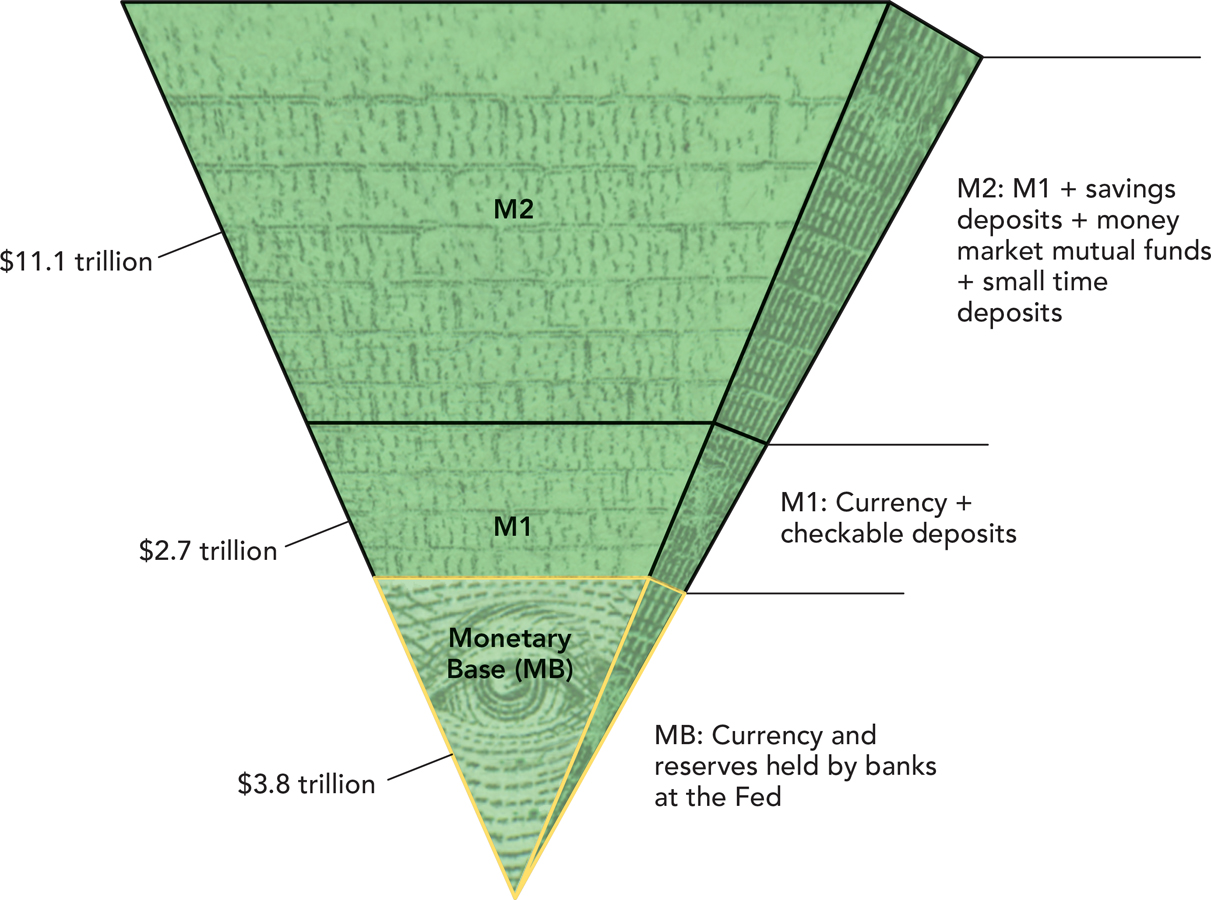

Economists have created many definitions of the money supply. The three most important are:

The monetary base (MB): Currency and total reserves held at the Fed

The monetary base (MB): Currency and total reserves held at the Fed

Ml: Currency plus checkable deposits

Ml: Currency plus checkable deposits

M2: Ml plus savings deposits, money market mutual funds, and small time deposits

M2: Ml plus savings deposits, money market mutual funds, and small time deposits

These definitions can be thought of as an inverted pyramid, as shown in Figure 15.2.

FIGURE 15.2

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve, 2014.

The Fed has direct control only over the monetary base. But it’s the other components of the money supply—Ml and M2—that have the most significant effects on aggregate demand. As we will discuss later in the chapter, the Fed can increase bank reserves, but if the banks aren’t lending, the increase in reserves won’t do much to increase aggregate demand.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 15.1

Define the monetary base.

Define the monetary base.

Question 15.2

What is the amount of currency in circulation compared to the amount of checkable deposits?

What is the amount of currency in circulation compared to the amount of checkable deposits?

The pyramid diagram therefore illustrates one difficulty of central banking. The central bank tries to use its control over MB to influence Ml and M2, but there are many other influences on Ml and M2 so each monetary aggregate can shrink or grow independently of the others. Finally, the Fed ultimately wants to steer aggregate demand, but once again its steering is sometimes wobbly because, although Ml and M2 influence aggregate demand, there are also other influences.

To understand how the Fed influences Ml and M2 but also why its influence is sometimes tenuous, we must introduce the concepts of fractional reserve banking, the reserve ratio, and the money multiplier.