Tax Revenues

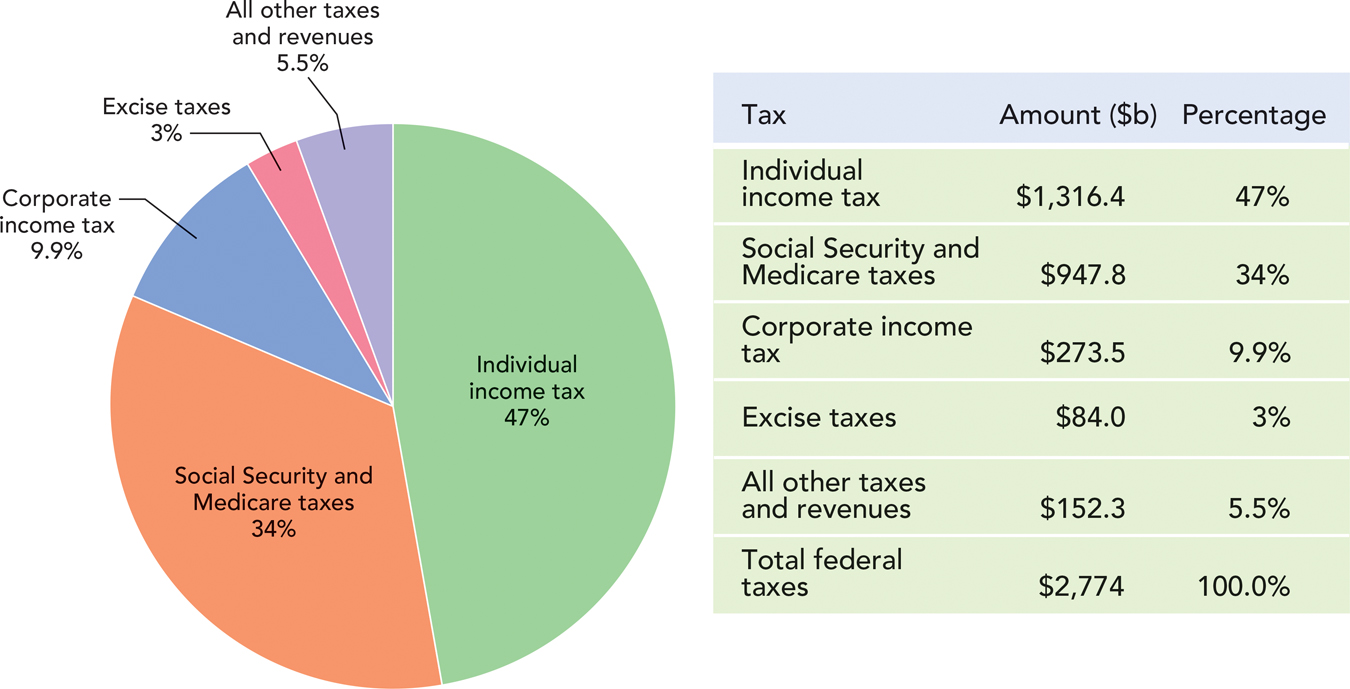

As of 2013, the federal government was taking in about $2.8 trillion a year, or nearly $9,000 for every man, woman, and child in the United States. The federal government takes in money in many ways, but three sources—the individual income tax, the Social Security and Medicare taxes, and the corporate income tax—account for more than 90% of the revenue. Figure 17.1 shows the major sources of revenue for the U.S. government.

FIGURE 17.1

The individual income tax is the single largest source of revenue for the federal government. The second category, Social Security and Medicare taxes (a few other smaller taxes are also included in this category), includes the “FICA tax” you have seen on your paycheck—these taxes are so named because unlike the income tax, the revenue from these taxes is tied to specific programs. Social Security and Medicare taxes have increased in recent decades and now bring in almost as much money as the income tax. Corporate income taxes are a distant third. The other sources are much smaller and they include excise taxes such as taxes on gasoline and alcohol, user fees, estate and gift taxes, and custom duties or tariffs. Let’s take a closer look at the three largest sources of revenue.

The Individual Income Tax

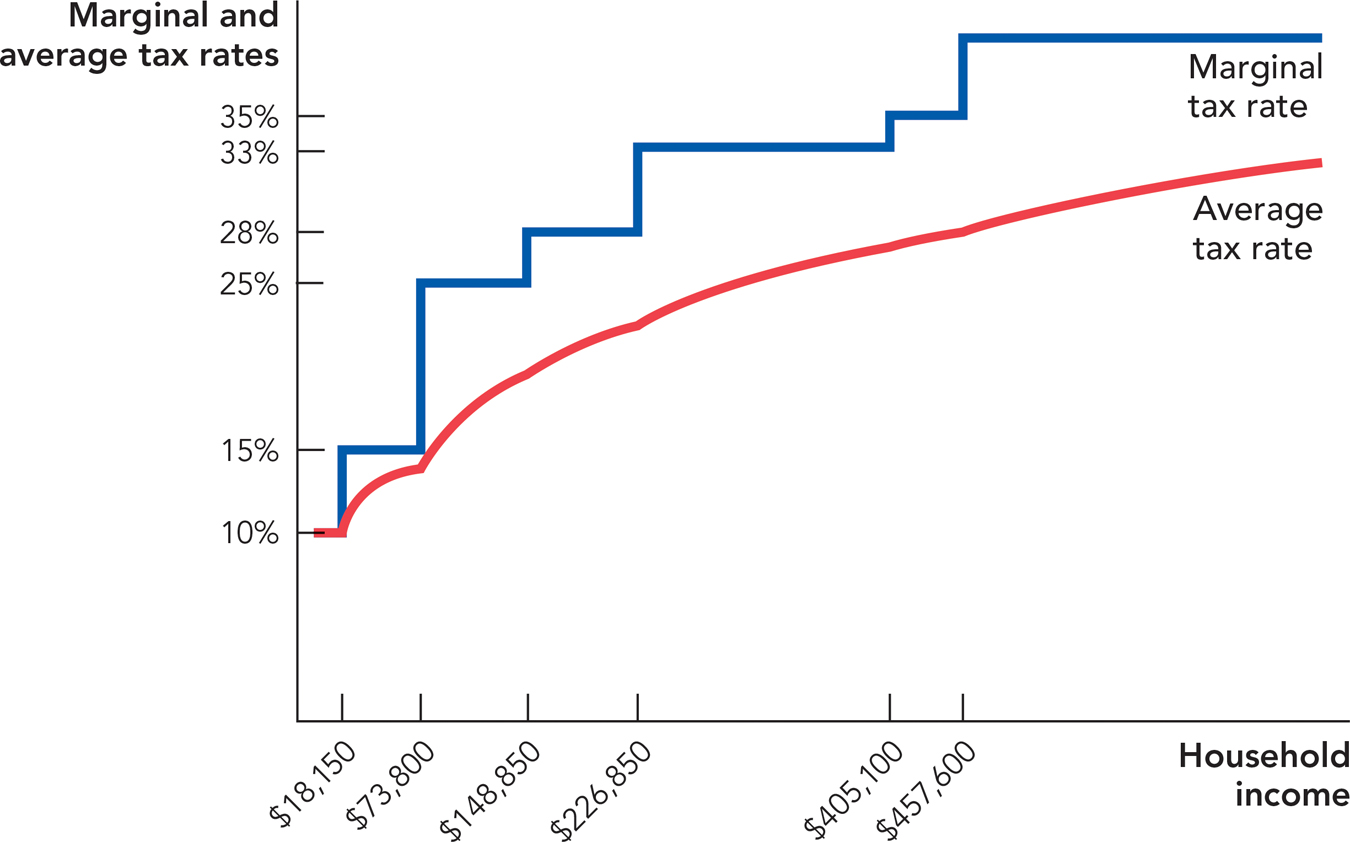

Most Americans are required to file an income tax return with the federal government. On this form a person reports his or her income and the tax code determines how much money is due. The 2014 schedule of marginal tax rates for someone who is married and filing jointly with a spouse, is shown in Figure 17.2 below.

FIGURE 17.2

The marginal tax rate is the tax rate paid on an additional dollar of income.

The marginal tax rate is the tax rate that you must pay on an additional dollar of income. Figure 17.2 tells us that if you earn less than $18,150, then the marginal tax rate, the rate on an additional dollar of income, is 10% (some deductions are allowed—). If you earn between $18,150 and $73,800, the rate of tax on an additional dollar of income is 15%. If you earn between $73,800 and $148,850, you must pay 25% of any additional income to the federal government. Marginal tax rates increase in uneven steps until the top marginal tax rate of 39.8% is reached on any income earned greater than $457,600.

We care about the marginal tax rate because, as usual in economics, it’s the marginal rate that matters for determining things like the incentive to work additional hours. If you are considering doing an extra carpentry job for spare cash, you don’t care what tax you are paying on the money you’ve already earned. You care about how much additional tax you will be paying on the extra money that you might earn if you choose to take the job.

Marginal tax rates today are lower and flatter than they have been in the past. In 1960, for example, the lowest marginal tax rate was 20% and the highest rate was 91%! Of course in the further past, rates were much lower than today. In 1913, when the income tax began, the top marginal rate was just 7% and that rate didn’t take effect until annual income was over $10 million (in today’s dollars).

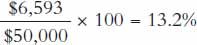

Your average tax rate is simply your total tax payment divided by your total income. If your income is $50,000, for example, then your total income tax under the current system can be calculated as follows. You pay 10% on the first $18,150, or $1,815, then you pay 15% on the next $31,850 ($50,000 − $18,150), or $4,778, for a total tax of $6,593. Your average tax rate is then

The average tax rate is the total tax payment divided by total income.

Unfortunately, the tax system is not quite as simple as we have presented so far because some income is exempt from taxation. Each person, for example, generally gets one tax exemption for him- or herself, one exemption for a spouse, and one exemption for each child or dependent. In 2014, for example, each exemption let you have $3,950 of your income tax free.1 If you have a child, for example, you can exempt $3,950 of your income from tax. If your marginal tax rate is 25%, that exemption means that your taxes fall by about $987 per year (0.25 x $3,950). In other words, the federal government, using the tax system, makes it cheaper to have another child compared to spending your money on, say, a new car. This also means that people with the same income may pay different tax amounts. The exemption amount is indexed for inflation so it typically increases a bit every year and it is phased out at higher incomes.

The tax system also allows for deductions. Like exemptions, deductions reduce your taxable income, but only if you have specific expenses. The most important deductions are for home mortgage interest, donations to charity, state and local taxes, and very high medical expenses.

For instance, if you buy a house, the interest payments on your mortgage can (usually) be deducted from your taxable income. So, if you are paying $1,000 a month in mortgage interest and you are facing a 25% marginal tax rate, the mortgage interest deduction will save you about $250 a month in taxes. Does this make buying a house cheaper? Not by as much as you might think. The tax deduction means that more people want to buy houses and that drives up the price of houses, especially in places like Manhattan where the amount of land is fixed. So, some of “your” subsidy actually ends up in the hands of landowners. In other words, who gets the check from the government is not necessarily the person who ends up with extra money in his or her pocket. More generally, economists understand that who really pays a tax or a subsidy can be quite different from who must send the check to the government or how those taxes and subsidies are described to the public. That point will not be the focus of this chapter—see your microeconomics textbook for more—but do keep it in mind as you think about the different taxes in the American economy.

Taxes on Capital Gains and Interest and Dividends The income tax is a tax on your labor income and also on any income you receive from your investments, namely your interest income, your dividends, and your capital gains. You receive interest income, for instance, on your savings and checking accounts, and this income usually is taxed as if it were labor income.

The taxation of capital gains is more complicated. You receive a capital gain, for instance, if you buy stock at $110 a share and later resell it at $210 a share. Your capital gain is the extra $100 you made from the rise in the value of the stock. You pay a tax on those profits and currently the standard capital gains tax rises from 0% for those with low incomes to 15% for most taxpayers to 20% for those whose income puts them in the highest income tax bracket. Capital gains taxes are paid only when the assets are actually sold and not in the meantime while the assets are simply being held.

As is often the case in our tax system, the real rates people pay are not the same as the rates written into the tax code. For instance, capital gains allow for “loss offsets.” If you gain $100 selling one stock and lose $100 selling another, usually the two sums cancel each other out in the calculation of your tax liability. If you know how to group your winners and losers together at the right time, the true rate of capital gains taxation you face may be much lower than the published rate of 15%.

Republicans and Democrats often disagree about how much investment income should be taxed. Democrats often favor higher taxes on investment income, on the grounds that the rich invest quite a bit and thus taxing investment income means the rich will bear a larger share of the tax burden. Republicans are more likely to argue that lower taxes on investment spur investment and thus economic growth, creating jobs, raising wages, and contributing to general prosperity in the long run.

Alternative minimum tax (AMT) is a separate income tax code that began in 1969 to prevent the rich from not paying income taxes. It was not indexed to inflation and is now an extra tax burden on many upper middle class families.

The Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) There is yet another complication to the American tax system, and that is the alternative minimum tax, or AMT. The AMT was started in 1969 after a televised congressional hearing revealed that 155 households with income over $200,000 (about $1.2 million in today’s dollars) had paid no income tax. These families had done nothing illegal, but they had managed to take advantage of tax laws to avoid income taxes. Thus, the original goal of the AMT was to make sure that it would not be possible for anyone to avoid all income tax.

The AMT requires taxpayers to make two computations. First, they must compute what they owe under the standard tax code; then, they must compute what they owe under the AMT, which is typically based on a flat rate of either 26% or 28%, with no deductions allowed. The taxpayer must then pay whichever number is higher.

The AMT was supposed to hit just a few hundred families among the super rich but it was never adjusted for inflation, so every year more and more people became subject to the AMT. In recent years, more than 4 million taxpayers paid the AMT and it’s now often the case that families earning $100,000 a year or less are paying the AMT and thus paying more taxes than under the regular tax code. The number of Americans covered by the AMT will likely continue to rise. The increasing reach of the AMT is, in fact, the largest tax increase in recent times, although it is rarely explained or presented as such. Both Republicans and Democrats claim they are unhappy about the growing reach of the AMT, but the two parties cannot agree on how to change or replace it, or how to make up for the lost revenue, should the AMT be restricted in its application.

Social Security and Medicare Taxes

Almost all workers in the United States pay the Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax, better known as the FICA tax, the acronym that you will see on your payroll check. The FICA tax is 6.2% of your wages on the first $117,000 of income. In addition, your employer also pays a 6.2% tax on the same earnings so the total FICA tax is 12.4%. The FICA taxes fund Social Security payments.

Many Americans believe, “I pay half of this tax, my employer pays the other half,” but this isn’t quite right. As we’ve already mentioned, the person who appears to pay a tax isn’t always the person who actually pays. In reality, economic research shows that the employer’s payment is mostly taken out of the worker’s prospective wage; in other words, if your employer didn’t have to pay the FICA tax, your wages would be higher.* Much of the burden of the FICA tax falls on workers, not on employers.

Medicare is partly financed out of general revenues and partly financed out of special payroll taxes. For most workers, 1.45% is withheld from their paychecks in the form of a Medicare premium and the employer pays another 1.45%. Again, workers pay much of the employer’s premium in the form of lower wages. Self-employed individuals pay the full 2.9% themselves.

The Corporate Income Tax

In the United States, the corporate income tax rate is generally 35%. This is one of the highest rates in the world. The rate of 35%, however, is applied to a legal measure of income, but the tax code is so constructed that a good accountant can often make corporate income come out very low, even for profitable corporations. In fact, some apparently profitable corporations manage to define their income and expenses in such a way that they often don’t pay any corporate income tax at all. Maybe you’ve heard of Boeing, the large and profitable airplane manufacturer; over a recent period of five years, the company paid an average tax rate of 0.7%.2 Other companies aren’t so well situated to take advantage of such tax breaks and accounting maneuvers.

Who pays the corporate income tax? Not corporations, which in the final analysis are legal fictions. All taxes are eventually paid by human beings. The corporate income tax is paid initially by shareholders and bondholders of corporations who earn a lower rate of return on their investments. More generally, the rate of return will fall on all forms of capital and in the long run that will also mean somewhat lower wages for workers and higher prices for goods and services.

The Bottom Line on the Distribution of Federal Taxes

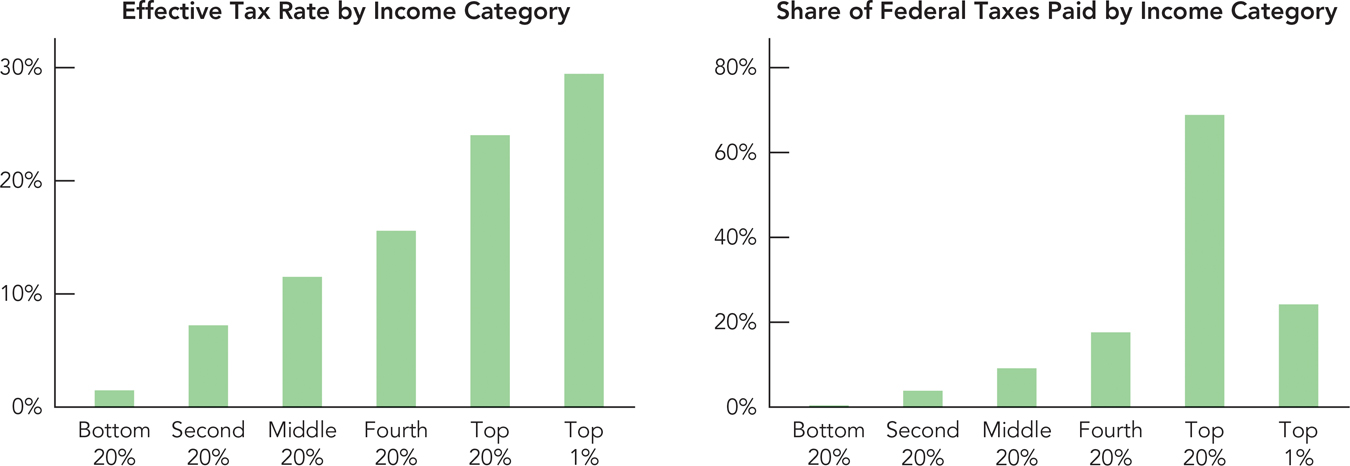

Once we add in deductions, exemptions, corporate taxes, payroll taxes, excise taxes, the AMT, and assumptions about tax incidence (who pays the tax), what is the final result? It’s not an easy calculation, but the best estimate of the distribution of federal taxes by income class is shown in Figure 17.3.

FIGURE 17.3

Note: Income includes market income and government transfers.

The left panel of Figure 17.3 shows that if we divide households into categories according to how much they earn, then households with incomes in the bottom 20% pay very little in federal tax, less than 5% of their total income. As income increases so does the effective rate, so those with incomes in the top 20% pay an effective tax rate of around 25%. The effective tax rate continues to rise if we look at those in the top 1% who pay nearly 30% of their income to the federal government.

A progressive tax has higher tax rates on people with higher incomes.

It is sometimes said that the rich do not pay taxes in the United States. That is false. Whether they pay enough taxes depends on your point of view, but despite all the deductions, exemptions, loopholes, and so forth, the U.S. tax system is progressive—people with higher income pay a higher percentage of their income in tax to the federal government than people with lower income.

A flat tax has a constant tax rate.

In contrast to a progressive tax is a flat tax, which has a constant tax rate applied to income at all levels of earning. If the tax code were radically simplified to eliminate almost all deductions, including the deductions for mortgage interest and charitable giving, then by some calculations a flat rate of around 19% would raise approximately the same revenue as today.3 A flat tax has a number of desirable properties. Simplification of the tax code would be appreciated by many taxpayers and elimination of deductions and loopholes would encourage people to make investment, consumption, and work decisions for good economic reasons rather than merely to reduce tax payments.

A regressive tax has higher tax rates on people with lower incomes.

The disadvantage of a flat tax is that moving to a flat tax would require lowering rates on the rich and raising rates on the middle class and poor. If you compare the effective tax rate paid by different income classes under the current tax code—shown in Figure 17.3—with a flat rate of 19%, you can see that tax rates for the rich and poor could change quite dramatically under a flat tax. Proponents of a flat tax, including Republican Steve Forbes and Democrat Jerry Brown, argue that the efficiency advantages of a flat tax mean that even people who paid a higher tax rate would, with increased economic growth, pay less in total tax.

Even if a flat tax were significantly more efficient than our current tax code, it’s hard to see how the United States could ever move to such a system. Do you remember what we said about the effect of the mortgage interest deduction on house prices? The mortgage interest deduction raises house prices, so eliminating the deduction would cause a fall in house prices. Is it any wonder that neither Jerry Brown’s nor Steve Forbes’s tax plans caught on when they ran for president? Other countries, including Russia, the Czech Republic, and Estonia, have moved toward a flat tax recently, however, so it will be interesting to see how they fare.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 17.1

Individual income taxes plus Social Security and Medicare taxes represent what percent of federal revenues? (Review Figure 17.1 if necessary.)

Individual income taxes plus Social Security and Medicare taxes represent what percent of federal revenues? (Review Figure 17.1 if necessary.)

Question 17.2

Consider Figure 17.3. Let’s start with a person in the fourth quintile, earning $80,000 pretax. Using the effective tax rate, what did this person pay in tax? Now consider a person in the top quintile who earns $160,000 pretax. What did this person pay in tax? Compare the amount of tax paid by both. Does this provide evidence that the tax system is progressive?

Consider Figure 17.3. Let’s start with a person in the fourth quintile, earning $80,000 pretax. Using the effective tax rate, what did this person pay in tax? Now consider a person in the top quintile who earns $160,000 pretax. What did this person pay in tax? Compare the amount of tax paid by both. Does this provide evidence that the tax system is progressive?

Returning to the current U.S. tax code, the effective tax rate is higher on the rich and the rich have more money—put these two things together and we can calculate who pays for the federal government. The right panel in Figure 17.3 shows the share of federal tax revenues that is paid for by each income category. The finding is that the rich, and especially the very rich, bear by far the largest share of the federal tax liability. Almost 70% of federal taxes are paid by people in the top 20% of income earners. The top 1% alone pay about one-quarter of all federal taxes.

State and Local Taxes In addition to federal taxes, most people pay state and local taxes, so the federal tax burden is not the end of the story. Overall, state and local taxes are about half the level of federal taxes, just under 10% of GDP Compared to the federal government, states raise more of their revenues, about 20% on average, from sales taxes. Since sales tax rates are the same for everyone, regardless of income, state and local taxation as a whole is less progressive than income taxation. Thus, state and local taxes probably make the overall tax system a little bit less progressive than the federal tax system, but it does depend on the state.