Spending

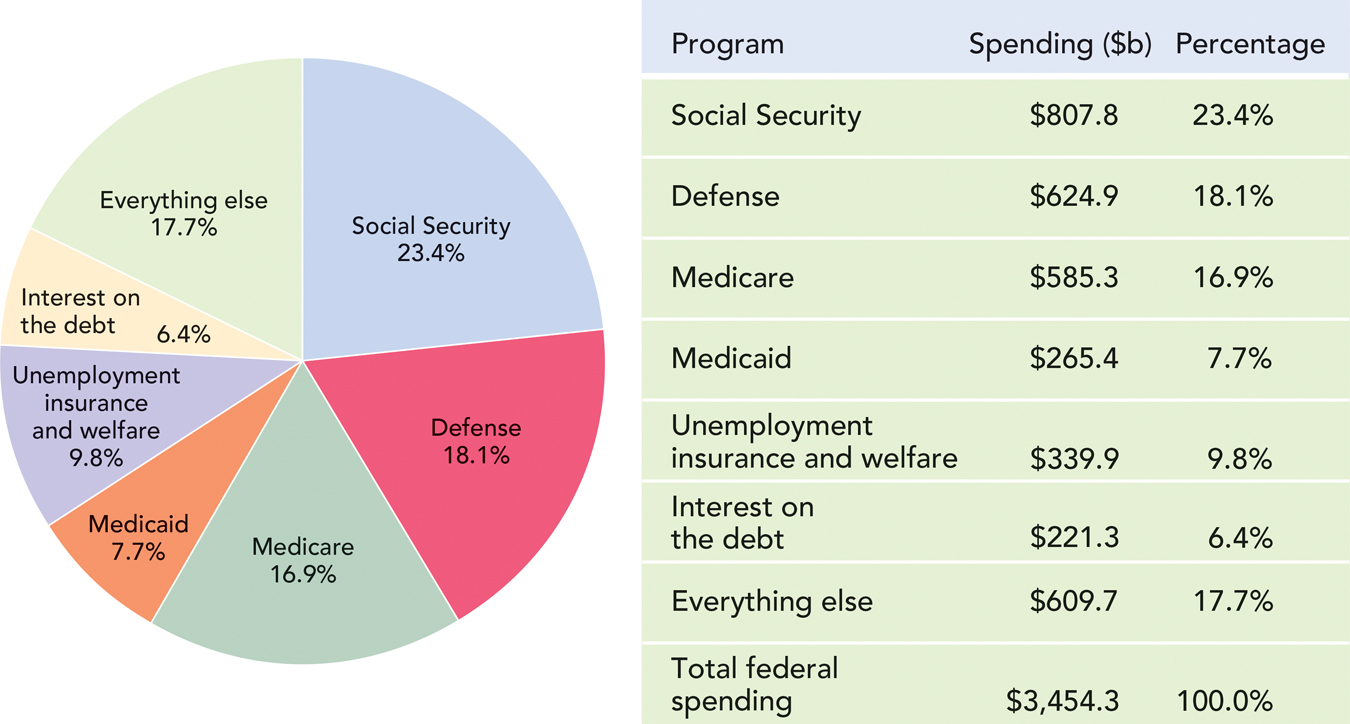

Almost two-thirds of the U.S. federal budget is spent on just four programs in a typical year: Social Security, defense, Medicare, and Medicaid, as seen in Figure 17.4. Interest on the national debt and various unemployment insurance programs and welfare programs are also large. Everything else—spending in roads, education, police, prisons, science and technology, agriculture, the environment, and the various stimulus programs intended to boost the economy— account for the remainder of the budget. Let’s take a closer look at the big items to see just where our tax money goes.

FIGURE 17.4

Social Security

If measured in terms of dollars paid out, Social Security is the single largest government program in the world. In 2013, $807.8 billion of benefits were paid to over 61 million beneficiaries.

We’ve already seen how the Social Security tax works. If you are wondering where that money goes, Social Security is run on a pay-as-you-go basis. That means that when the government takes in your dollars, the money does not go into an account or trust with your name on it. The money is shipped out right away to the current elderly, who of course are receiving benefits. When you become old, you’ll get your benefits from taxes on the young at that later point in time.

Every year the federal government sends Americans letters telling us how much money is in “our” personal social security accounts. Don’t be misled. There is no money in “your account”; there isn’t a “your account” at all. Those letters are just the government’s prediction of how much you’ll get back some day. Of course, since you are in the meantime a voter, don’t be surprised if those predictions turn out to be a little bit optimistic.

Social Security benefits are defined by a complex formula depending on how many years a worker worked, what their average earnings were over their working life, whether or not they are married, what year they retire, and at what age. In recent years, the average retiree has been paid $1,200 a month so one immediate lesson is that you shouldn’t count on Social Security alone to support you in your old age.

The age at which workers can claim their full retirement benefits was 65 for many years but, because the Social Security program was getting very expensive, in 1983, the full retirement age was made to slowly increase depending on when the worker was born. You—assuming you were born after 1960—must wait until age 67 to claim your full retirement benefits. Some people advocate increasing the full retirement age again, so you may want to keep an eye on the age at which you will be able to claim full benefits. A worker can start claiming some benefits as early as age 62, but people who opt for early retirement get a lower monthly payment. Benefits are indexed to the level of wages in the United States, so over time benefits rise automatically with general increases in prosperity.

Do you recall Ida May Fuller from the introduction? She paid $24.75 in Social Security taxes and received $22,888.92 in payments. Ida May’s example is extreme but the basic idea is quite general. Workers who retired in the early years of Social Security received full benefits even though they paid Social Security taxes for only a portion of their working life. In addition, the Social Security tax rate increased over time, rising from 2% in 1940 to today’s rate of 12.4%. The higher tax rate on today’s workers funds larger benefits for yesterday’s workers— even though yesterday’s workers paid a lower tax rate on their earnings.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that Social Security has become less generous over time. To see how generous Social Security is, we can add up all the taxes an individual can expect to pay into Social Security and then subtract all the benefits an individual can expect to receive from Social Security, being sure to adjust for the fact that taxes must be paid before benefits are received (a present value calculation; note that the concept of present value has been defined in the appendix to Chapter 9). Table 17.1 does just this for a single male worker with different average wages and retiring in different years.

TABLE 17.1 Net Benefits of Social Security (Single male assuming various retirement years and average wages)

|

Average Wages |

Retiree Turned 65 in 1975 |

Retiree Turned 65 in 2010 |

Retiree Turns 65 in 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Low |

$46,807 |

$8,286 |

$3,062 |

|

Medium |

$53,999 |

−$43,255 |

−$85,945 |

|

High |

$52,284 |

−$95,212 |

−$193,874 |

|

Source: Steuerle, C. Eugene, and Adam Carasso. 2004. The USA TODAY Lifetime Social Security and Medicare Benefits Calculator Assumptions and Methods, http://www.urban.org/retirement_policy/url.cfm?ID=900746. Low, medium, and high earnings are $30,000, $60,000, and $120,000 in inflation-adjusted 2004 dollars. |

|||

Table 17.1 tells us that a single male with low lifetime earnings who retired in 1975 received $46,807 more in Social Security benefits over his prospective lifetime than he paid in taxes. Now consider the same low-wage worker except that now he retired in 2010 instead of 1975—this worker can expect to receive only $8,286 more in benefits than he pays in taxes. If the same worker retires in 2030, he can expect to receive just $3,062 more in benefits than he pays in taxes. Thus, the Social Security program is becoming less generous over time, in large part because the program was very generous to workers in its early years.

We can also see from Table 17.1 that Social Security redistributes wealth across income classes. A low-wage worker who retires in 2030 will receive $3,062 more in benefits than he pays in taxes, but for medium- and high-wage workers Social Security is a net cost. A medium-wage worker retiring in 2030 will pay $85,945 more in Social Security taxes than he will receive in benefits and a high-wage worker will pay $193,874 more in taxes than he will receive in benefits. Thus, Social Security is not just a retirement system—it’s also a welfare system.

As usual, there are complications, only three of which we will mention here. Social Security pays more to married couples than to singles. A married man gets 50% more than a single man with the same earnings, even if his spouse has never worked. (The same is true for married females with nonworking spouses.) Thus, Social Security is more beneficial for married people than singles.

Social Security pays more the longer you live, so anyone with greater life expectancy gets a bigger benefit from Social Security (remember Ida May Fuller lived to 100!). Similarly, anyone with lower life expectancy doesn’t get as good a deal from Social Security as he or she would otherwise. If you are 55, for example, and your doctor tells you that you have five years left to live, you don’t get to make an early withdrawal from “your” Social Security account.

Because Social Security redistributes toward those with higher life expectancy, it’s better for females than for males. In other words, a single woman with the same earnings as a single man will get more from Social Security because, on average, she will live longer. More generally, different individuals are treated differently by Social Security depending on their wealth, life expectancy, marriage status, and other factors.

Defense

In 2013, the official budget for the Department of Defense, plus the costs of military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, was about $625 billion. Even these figures, however, don’t include spending on veterans’ benefits, homeland security, nuclear weapons research, or costs of military-style operations that run through the CIA or other non-Defense Department agencies. A broader definition for defense would increase defense spending to around $750 billion annually.

The United States spends much more on its military than does any other country in the world. Table 17.2 presents some data on the top 10 countries by military expenditure in 2013. Do we get value for our money? Unfortunately, assessing how much we should spend on the military goes well beyond standard economics and into issues of foreign policy. That is an important question but it isn’t a topic for this book.

TABLE 17.2 Top Ten Countries by Military Expenditure (billions of U.S. dollars)

|

Country |

Military Expenditure (billions) |

|---|---|

|

United States |

$640 |

|

People’s Republic of China |

$188 |

|

Russia |

$87.8 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

$67 |

|

France |

$61.2 |

|

United Kingdom |

$57.9 |

|

Germany |

$48.8 |

|

Japan |

$48.6 |

|

India |

$47.4 |

|

South Korea |

$33.9 |

|

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. |

|

Medicare and Medicaid

Medicare reimburses the elderly for much of their medical care spending, covering hospital stays, doctor bills, and prescription drugs. To be eligible for Medicare, an individual should be 65 or older and have worked for at least 10 years in a job paying Medicare premiums. Many of the disabled are covered as well, even if they have not held such jobs.

In fiscal year 2013, Medicare spending amounted to $585 billion. Social Security and Medicare, taken together, are by far the largest undertakings of the U.S. government, and both are programs that transfer money to the elderly.

Medicare does not pay all medical bills outright. Instead, beneficiaries are required to pay some percent of the charges, known as a “copayment.” A beneficiary also has to pay for relatively small charges, which is known as a “deductible.” Many of the elderly buy private insurance to pay for the gaps in their Medicare coverage.

In addition to Medicare, you may have heard of Medicaid. Whereas Medicare covers the elderly, Medicaid covers the poor and the disabled. Of course, some of the elderly are poor as well and these people are eligible for both programs. The federal government and state governments pay for Medicaid jointly, but the program itself is run through state governments at the state level. As of fiscal 2013, Medicaid expenditures were around $265 billion. Spending on Medicaid and health care more generally will be changing in the next few years as the Affordable Care Act signed by President Barack Obama in 2010 modifies the American health insurance system.

Unemployment Insurance and Welfare Spending

It is a common myth that most of the money spent by our federal government goes to welfare programs. In reality, federal welfare payments (not including Medicaid or unemployment insurance) amount to $150-300 billion a year (depending on exactly what one counts and whether the economy is in a recession). These are substantial figures, but other programs are much larger.

Remember, other than defense, the largest spending programs are Social Security and Medicare, and these programs primarily transfer wealth to the elderly, not to the poor. Since we will all be elderly sooner or later (at least if we are lucky), these transfers eventually go to virtually all Americans.

Most welfare payments fall into a few common categories. First, personal welfare payments are made to poor households with children. The largest of these is called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. Since 1996, an individual cannot receive these benefits for more than five years in a lifetime. Housing vouchers under the Section 8 program give poor households a voucher that subsidizes a portion of their rent.

Especially important is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which is now the main form that antipoverty policy takes at the federal level. The EITC, quite simply, pays poor people cash through the tax system depending on how much they earn. So, for instance, if you are married, have a child, and earn $20,000 a year, you are below the poverty line and the EITC will supplement your income, giving you over $3,000 for the year. With more than one child, the credit goes up to almost $4,000. In 2013, just under $63 billion was spent on the EITC and these federal programs are supplemented by a wide variety of state and local welfare programs for the poor.

Unemployment insurance (UI) makes payments to people who are out of work and is not restricted to the poor. UI is a large program that can expand rapidly during recessions. In 2007, for example, just $31.4 billion was spent on UI but with the recession and emergency benefits, that number increased to $155 billion in 2010 before falling to $72 billion in 2013.

Everything Else

Before discussing paying interest on the national debt, let’s look at everything else. Everything else accounts for all the other spending programs of the federal government, which include:

Farm subsidies.

Farm subsidies.

Spending on roads, bridges, and infrastructure. The Disaster Relief Fund.

Spending on roads, bridges, and infrastructure. The Disaster Relief Fund.

The Small Business Administration.

The Small Business Administration.

The Food and Drug Administration.

The Food and Drug Administration.

All federal courts.

All federal courts.

Federal prisons.

Federal prisons.

The FBI.

The FBI.

Foreign aid.

Foreign aid.

Border security.

Border security.

NASA.

NASA.

The National Institutes of Health.

The National Institutes of Health.

The National Science Foundation.

The National Science Foundation.

Financial assistance to students.

Financial assistance to students.

The wages of all federal employees.

The wages of all federal employees.

All of these programs add up to a large amount of money, but none of these programs is large compared to Social Security, defense, or Medicare.

A common misconception about the budget involves foreign aid. When polled, 41% of Americans said that foreign aid is one of the two largest sources of federal expenditure. In reality, foreign aid is about 1% of the overall federal budget; the exact number depends on how that term is defined since sometimes “foreign aid” and “military assistance” are difficult to distinguish.