Will the U.S. Government Go Bankrupt?

We said earlier that the current debt-to-GDP ratio of 73% is large but not unprecedented. Nevertheless, many economists are worried about the future debt-to-GDP ratio.

The main forces driving these worries are not recessions but demographics and increasing health-care costs. The U.S. population is getting older. In 2011, about 13.1% of the population was aged 65 or older, but in 2030, 19% of the population will be 65 or older. The increase in the number of elderly people means higher Social Security and Medicare payments. As a fraction of GDP, for example, Social Security payments will have to increase by about 41% if benefits are to be maintained at promised levels. More elderly people also means we will see increases in Medicare payments, although in this case an even bigger problem than demographics is rising health-care costs per person.

Because of Medicare, Medicaid, and health insurance subsidies, health-care costs will consume a larger and larger share of the federal budget. As health-care costs increase, pressure will be put on everything else and some combination of increased taxes, reduced spending on other items, or higher debt must come to pass.

In recent decades, health-care costs per person have been rising more than twice as fast as GDP per capita. If health-care costs continue rising at their current rate, those costs will account for a larger and larger part of the economy.

The Future Is Hard to Predict

So what will happen? Will spending decrease or will taxes increase? No one knows. You may have heard about competing plans to solve this problem, including the Ryan Plan, Simpson-Bowles Plan, and Gang of Six Plan. (Really, we are not making this up.) Each of these plans tries to solve the growing debt problem with a combination of spending cuts and tax increases, with some plans emphasizing the former and some the latter. The American public has yet to decide which way it will vote. On the one hand, the United States does have a history of relatively low taxes. Americans fought the Revolutionary War, in part, as a protest against British taxes even though British Americans had one of the smallest tax burdens in the world! The modern income tax didn’t begin until 1913 and that required a separate amendment to the Constitution. Even as late as 1916, the federal government accounted for less than 5% of GDP.

Taxes and federal spending increased dramatically during 1916-1919 and 1942–1945, corresponding to World War I and World War II, respectively. But since that time federal taxes and spending have been fairly stable—as we noted, around 18% of GDP. When taxes have increased, there have often been backlashes with Americans electing politicians who promise to cut taxes. So, will Americans accept much higher tax rates in the future than they ever have in the past? Will you?

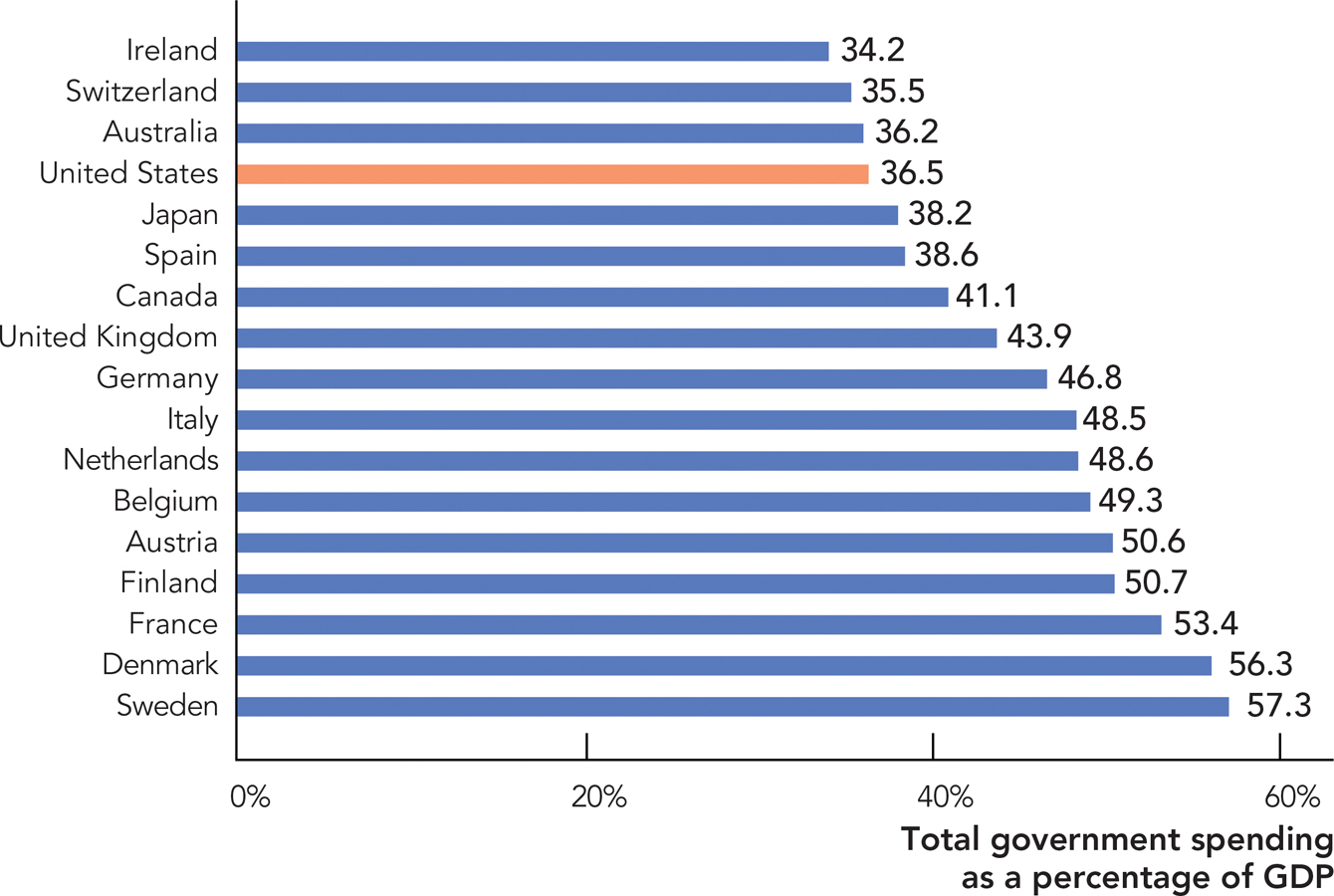

If taxes and spending in the United States do increase, this would make the United States more like other developed countries. Figure 17.7 shows total government spending by country, including spending by federal, state, and local governments. Government in the United States today spends a smaller fraction of GDP than in most other developed countries. As a result, spending could increase substantially in the United States over the next several decades and the United States would still be spending at levels comparable to Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands today.

FIGURE 17.7

Could spending be cut? We have already cut some projected Social Security spending by increasing the age of retirement. Perhaps we can cut spending even more—but don’t expect the elderly to take this sitting down! And remember a large part of the growth in spending is due to rising health-care costs. Many people talk about slowing the growth of health-care costs but it isn’t so easy. There is a lot of waste in health-care markets, but also there are many wonderful innovations. Drugs known as statins lower our cholesterol and new surgical procedures save many lives; a triple bypass operation is now more or less standard procedure. It’s not so easy to sort out the good medical procedures from the bad ones, and so by most accounts health-care costs will continue to rise. Other countries do spend a smaller fraction of their GDP on health-care costs, but the growth in health-care costs is fairly similar throughout the developed world.

Don’t forget that whatever happens, the news is actually quite good for the most part. Americans are living longer than ever before and many medical advances are paying off. Let’s say you thought you would live to be 80 but then you learn you will live to be 100 instead. You might worry about how to finance your now-longer retirement and perhaps you might even despair that it seems impossible. But this is the kind of problem that we can live with!

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 17.5

Projecting forward for the next 40 years, what categories of spending are likely to increase or decrease? What does this mean for overall government spending? Will it grow, fall, or stay the same?

Projecting forward for the next 40 years, what categories of spending are likely to increase or decrease? What does this mean for overall government spending? Will it grow, fall, or stay the same?

Question 17.6

If the pace of idea generation quickens, as was discussed in Chapter 8, the long-run aggregate supply growth curve might shift permanently. If this happens, how would it affect the debt-to-GDP ratio? Explain what this means for our nation’s ability to pay for increased benefits for retirees.

If the pace of idea generation quickens, as was discussed in Chapter 8, the long-run aggregate supply growth curve might shift permanently. If this happens, how would it affect the debt-to-GDP ratio? Explain what this means for our nation’s ability to pay for increased benefits for retirees.

Another scenario is that GDP will grow faster in the future than it has in the past. We outlined one case for optimism in Chapter 8. Nevertheless, although we hope for the best, it’s probably wise to plan if not for the worst then at least for the most likely outcome, and that will require some painful tax increases or spending cuts.

One general lesson is that we cannot judge the fiscal health of the federal government simply by looking at today’s budget or today’s deficit. New government programs often grow over time and we ought to think about implicit future spending commitments when evaluating these new programs. Politicians in the past made many promises to spend in the future and today we are dealing with the legacy of these promises.