CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 21.6

1. Which of the following is the smallest fraction of the U.S. federal budget? Which are the two largest categories of federal spending?

Welfare

Interest on the federal debt

Defense

Foreign aid

Social Security

Health care

Question 21.7

2.

How many famines have occurred in functioning democracies?

What percentage of famines occurred in countries without functioning democracies?

Question 21.8

3. Around 130 million voters participated in the 2012 U.S. presidential election. Imagine that you are deciding whether to vote in the next presidential election. What do you think is the probability that your vote will determine the outcome of the election? Is it greater than 1%, between 1% and 0.1%, between 0.1% and 0.01%, or less than 0.01% (i.e., less than 1 in 10,000)?

Question 21.9

4. If a particular government policy—like a decision to go to war or to raise taxes—works only when citizens are informed, is that an argument for that policy or against that policy?

Question 21.10

5. True or false?

During Bangladesh’s worst famine, average food per person was much lower than usual.

Democracies are less likely to kill their own citizens than other kinds of governments.

Surprisingly, newspapers aren’t that important for informing voters about hungry citizens.

Compared with dictatorship or oligarchy, democracies have a stronger incentive to make the economic pie bigger.

Compared with most other countries, full democracies tend to put a lot of restrictions on markets and property rights.

When it comes to disposable income, American presidents seem to prefer “making a good first impression” rather than “going out with a bang.”

When the government owns most of the TV and radio stations, it’s motivated to serve the public interest, so voters tend to get better, less biased information.

Question 21.11

6. The median voter theorem is sometimes called the “pivotal voter theorem.” This is actually a fairly good way to think of the theorem. Why?

Question 21.12

7. Perhaps it was in elementary school that you first realized that if everyone in the world gave you a penny, you’d become fantastically rich. This insight is at the core of modern politics. Sort the following government policies into “concentrated benefits” and “diffuse benefits.”

Social Security

Tax cuts for families

Social Security Disability Insurance for the severely disabled

National Park Service spending for remote trails

National Park Service spending on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Tax cuts for people making more than $250,000 per year

Sugar quotas

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 21.13

1. David Mayhew’s classic book Congress: The Electoral Connection argued that members of Congress face strong incentives to put most of their efforts into highly visible activities like foreign travel and ribbon-cutting ceremonies, instead of actually running the government. How does the rational ignorance of voters explain why politicians put so much effort into these highly visible activities?

Question 21.14

2. An initiative on Arizona’s 2006 ballot would have handed out a $1 million lottery prize every election: The only way to enter the lottery would be to vote in a primary or general election. How do you think a lottery like this would influence voter ignorance?

Question 21.15

3. We mentioned that voters are myopic, mostly paying attention to how the economy is doing in the few months before a presidential election. If they want to be rational, what should they do instead? In particular, should they pay attention to all four years of the economy, just the first year, just the last two years, or some other combination?

Question 21.16

4. In his book The Myth of the Rational Voter, our GMU colleague Bryan Caplan argues that not only can voters be rationally ignorant, they can even be rationally irrational. People in general seem to enjoy believing in some types of false ideas. If this is true, then they won’t challenge their own beliefs unless the cost of holding these beliefs is high. Instead, they’ll enjoy their delusion.

Let’s consider two examples:

John has watched a lot of Bruce Lee movies and likes to think that he is a champion of the martial arts who can whip any other man in a fight. One night, John is in a bar and he gets into a dispute with another man. Will John act on his beliefs and act aggressively, or do you think he is more likely to rationally calculate the probability of injury and seek to avoid confrontation?

John has watched a lot of war movies and likes to think that his country is a champion of the military arts that can whip any other country in a fight. John’s country gets into a dispute with another country. John and everyone else in his country go to the polls to vote on war. Will John act on his beliefs and vote for aggression, or do you think he is more likely to rationally calculate the probability of defeat and seek to avoid confrontation?

Question 21.17

5. In the television show Scrubs, the main character J. D. is a competent and knowledgeable doctor. He also has very little information outside of the field of medicine, admitting he doesn’t know the difference between a senator and a representative and believes New Zealand is near “Old Zealand.”

Suppose J. D. spends some time learning some of these common facts. What benefits would he receive as a result? (Assume there are no benefits for the sake of knowledge itself.)

Suppose instead J. D. spends that time learning how to diagnose a rare disease that has a slight possibility of showing up in one of his patients. What benefits would he receive as a result? (Again, assume there are no benefits for the sake of knowledge itself.)

Make an economic argument that even given your answer to part b, voters have too little incentive to be informed about political matters.

Question 21.18

6. Driving along America’s interstates, you’ll notice that few rest areas have commercial businesses. Vending machines are the only reliable source of food or drink, much to the annoyance of the weary traveler looking for a hot meal. Thank the National Association of Truck Stop Operators (NATSO), who consistently lobby the U.S. government to deny commercialization. They argue:

Interchange businesses cannot compete with commercialized rest areas, which are conveniently located on the highway right-of-way … Rest area commercialization results in an unfair competitive environment for privately-operated interchange businesses and will ultimately destroy a successful economic business model that has proven beneficial for both consumers and businesses.9

How does NATSO make travel more expensive for consumers?

Do you think most Americans have heard of NATSO and the legislation to commercialize rest stops? How does your answer illustrate rational ignorance? Do you think that the owners of interchange businesses (i.e., restaurants, gas stations, and other businesses located near but not on highways) have heard of NATSO?

Why does NATSO often succeed in its lobbying efforts despite your answer to part a? (Hint: What is the concentrated benefit in this story? What is the diffused cost?)

Question 21.19

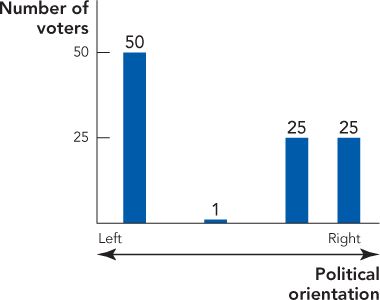

7. The following figure shows the political leanings of 101 voters. Voters will vote for the candidate who is closest to them on the spectrum, as in the typical median voter story. Again as usual, politicians compete against each other, entering the “political market” just as freely as firms enter the economic market back in Chapter 11.

Which group of voters will get their exact wish: the group on the left, the center-left, the center-right, or the right?

Now, four years later, it’s time for a new election. Suppose that in the meantime, the two right-leaning groups of voters have merged: The 25 center-right voters move to the far right, forming a far-right coalition. In the new election, whose position will win now?

As you’ve just seen, there’s a “pivotal voter” in this model. Who is it?

Let’s rewrite a sentence from the chapter concerning the Roman Empire: “As the American Empire grew, courting politicians in Washington became a more secure path to riches than starting a new business.” Does this seem true today? If it started happening, how would you be able to tell? In your answer, put some emphasis on market signals that could point in favor or against the “decadent empire” theory. (Hint: By some measures, Moscow has the highest real estate prices in the world, and it’s probably not due to low housing supply.)

CHALLENGES

Question 21.20

1. Is rational ignorance the whole explanation for why voters allow programs like the sugar quota to persist? Perhaps not. In the early 1900s, the government of New York City was controlled by a Democratic Party organization known as Tammany Hall. In a delightful essay entitled “Honest Graft and Dishonest Graft” by George Plunkitt, one of the most successful politicians from the Tammany machine, he argued that voters actually approve of these kinds of government-granted favors. (The essay and the entire book, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall: A Series of Very Plain Talks on Very Practical Politics, are available for free online.)

For example, Plunkitt said that ordinary voters like it when government workers get paid more than the market wage: “The Wall Street banker thinks it is shameful to raise a [government] clerk’s salary from $1500 to $1800, but every man who draws a salary himself says, ‘That’s all right. I wish it was me.’ And he feels very much like votin’ the Tammany ticket on election day, just out of sympathy.”

Plunkitt said this in the early 1900s. Do you think this is more true today than it was back then, or less true? Why?

If more Americans knew about the sugar quota, do you think they would be outraged? Or would they approve, saying, “That’s all right, I wish it was me”? Why?

Overall, do you think that real-world voters prefer a party that gives special favors to narrow groups, even if those voters aren’t in the favored group? Why?

Question 21.21

2.

When a drought hits a country, and a famine is possible, what probably falls more: the demand for food or the demand for haircuts? Why?

Who probably suffers more from a deep drought: people who own farms or people who own barbershops? (Note: The answer is on page 164 of Sen’s summary of his life’s work, Development as Freedom.)

Sen emphasizes that “lack of buying power” is more important during a famine than “lack of food.” How does Sen’s barber story illustrate this?

Question 21.22

3. Political scientist Jeffrey Friedman and law professor Ilya Somin say that since voters are largely ignorant, that is an argument for keeping government simple. Government, they say, should stick to a few basic tasks. That way, rationally ignorant voters can keep track of their government by simply catching a few bits of the news between reruns of How I Met Your Mother.

What might such a government look like? In particular, what policies and programs are too complicated for today’s voters to easily monitor? Just consider the U.S. federal government in your answer.

Which current government programs and policies are fairly easy for modern voters to monitor? What programs do you think that you and your family have a good handle on?

Can you think of easy replacements for the too complex programs in part a? For instance, cutting one check per farmer and posting the amount on a Web site might be easier to monitor than the hundreds of farm subsidies and low-interest farm loans that exist today.

Question 21.23

4. We mentioned that the median voter theorem doesn’t always work, and sometimes a winning policy doesn’t exist. This fact has driven economists and political scientists to write thousands of papers and books, both proving that fact and trying to find good workarounds. The most famous theoretical example of how voting doesn’t work is the Condorcet paradox. The Marquis de Condorcet, a French nobleman in the 1700s, wondered what would happen if three voters had the preferences like the ones in the following table. Three friends are holding a vote to see which French economist they should read in their study group. Here are their preferences:

|

|

Jean |

Marie |

Claude |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1st choice |

Walras |

Bastiat |

Say |

|

2nd choice |

Bastiat |

Say |

Walras |

|

3rd choice |

Say |

Walras |

Bastiat |

They vote by majority rule. If the vote is Walras vs. Say, who will win? Say vs. Bastiat? Bastiat v. Walras?

Page 473They decide to vote in a single-elimination tournament: Two votes and the winner of the first round proceeds on to the final round. This is the way many sporting events and legislatures work. Now, suppose that Jean is in charge of deciding in which order to hold the votes. He wants to make sure that his favorite, Walras, wins the final vote. How should he stack the order of voting to make sure Walras wins?

Now, suppose that Claude is in charge instead: How would Claude stack the votes?

And Marie? Comment on the importance of being the agenda setter.

(In case you think these examples are unusual, they’re not. Any kind of voting that involves dividing a fixed number of dollars can easily wind up the same way—check for yourself! Condorcet himself experienced another form of democratic failure: He died in prison, a victim of the French Revolution that he supported.)

Question 21.24

5. In the previous question, you showed that sometimes there may be no policy that beats every other policy in a majority rule election and, as a result, the agenda can determine the outcome. In the previous question, all of the policy choices on the agenda were as good as any other, but this is not always the case. Imagine that three voters, L, M, and R, are choosing among seven candidates. The preferences of the voters are given in the following table. Voter M, for example, likes Grumpy the best and Doc the least.

|

Preferences for President of Voters L, M, R |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Voter L |

Voter M |

Voter R |

|

1st Choice |

Happy |

Grumpy |

Dopey |

|

2nd Choice |

Sneezy |

Dopey |

Happy |

|

3rd Choice |

Grumpy |

Happy |

Sleepy |

|

4th Choice |

Dopey |

Bashful |

Sneezy |

|

5th Choice |

Doc |

Sleepy |

Grumpy |

|

6th Choice |

Bashful |

Sneezy |

Doc |

|

7th Choice |

Sleepy |

Doc |

Bashful |

Imagine that we vote according to a given agenda starting with Happy vs. Dopey. Who wins? We will help you with this one. Voter L ranks Happy above Dopey, so voter L will vote for Happy. Voter M prefers Dopey to Happy, so voter M will vote for Dopey. Voter R ranks Dopey above Happy so voter R will vote for Dopey. So ________ wins.

Now take the winner from part a and match him against Grumpy. Who wins?

Now take the winner from part b and match him against Sneezy. Who wins?

Now take the winner from part c and match him against Sleepy. Who wins?

Now take the winner from part d and match him against Bashful. Who wins?

Finally, take the winner from part e and match him against Doc. Who wins?

We have now run through the entire agenda so the winner from part f is the final winner. Here is the point. Look carefully at the preferences of the three voters. Compare the preferences of each voter for Happy (or Grumpy or Dopey) with the final winner. Fill in the blank: Majority rule has led to an outcome that ________ voter regards as worse than some other possible outcome. The answer to this question should shock you.

(This question is drawn from the classic and highly recommended introduction to game theory, Thinking Strategically by Avinash K. Dixit and Barry J. Nalebuff [New York: W.W. Norton, 1993].)

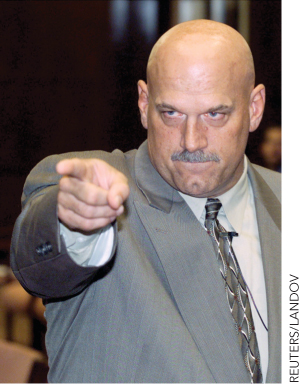

Question 21.25

6. In the 1998 Minnesota gubernatorial election, there were three main candidates: Norm Coleman (the Republican), Jesse “The Body” Ventura (an Independent), and Hubert Humphrey (the Democrat). Although we can’t know for certain, the voters probably ranked the candidates in a way similar to that found in the following table. The table tells us, for example, that 35% of the voters ranked Coleman first, Humphrey second, and Ventura third; and 20% of the voters ranked Ventura first, Coleman second, and Humphrey third; and so forth.

|

Minnesota Gubernatorial Election, 1998 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rank |

35% |

28% |

20% |

17% |

|

1 |

Coleman |

Humphrey |

Ventura |

Ventura |

|

2 |

Humphrey |

Coleman |

Coleman |

Humphrey |

|

3 |

Ventura |

Ventura |

Humphrey |

Coleman |

Suppose the election is by plurality rule, which means that the candidate with the most first place votes wins the election. Who wins in this case?

In Challenges question 4, you were introduced to the Marquis de Condorcet. Today, voting theorists call a candidate a Condorcet winner if he or she can beat every other candidate in a series of 1:1 or “face-off” elections. Question 4 showed you that in some cases, there is no Condorcet winner. What about in the gubernatorial election of 1998?

A Condorcet winner beats every other candidate in a face-off. A Condorcet loser loses to every other candidate in a face-off. Was there a Condorcet loser in the 1998 Minnesota gubernatorial election (given the preferences we have estimated)?

WORK IT OUT

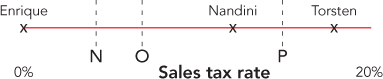

Let’s walk through the median voter theorem in a little more detail. Consider a town with three voters, Enrique, Nandini, and Torsten. The big issue in the upcoming election is how high the sales tax rate should be. As you’ll learn in macroeconomics (and in real life), on average, a government that wants to do more spending has to bring in more taxes, so “higher permanent taxes” is the same as “higher government spending.” Enrique wants low taxes and small government, Nandini is in the middle, and Torsten wants the biggest town government of the three. Each one is a stubborn person, and his or her favorite position—what economic theorists call the “ideal point”—never changes in this problem. Their preferences can be summed up like this, with the x denoting each person’s favorite tax rate:

Suppose there are two politicians running for office, N and O. Who will vote for N? Who will vote for O? Which candidate will win the election?

O drops out of the campaign after the local paper reports that he hasn’t paid his sales taxes in years. P enters the race, pushing for higher taxes, so it’s N vs. P. Voters prefer the candidate who is closest to them, as in the text. Who will vote for N? Who will vote for P? Who will win? Who will lose?

In part b, you decided who was heading for a loss. You get a job as the campaign manager for this candidate just a month before election day. You advise her to retool her campaign and come up with a new position on the sales tax. Of course, in politics as in life, there’s more than one way to win, so give your boss a choice: Provide her with two different positions on the sales tax, both of which would beat the would-be winner from part b. She’ll make the final pick herself.

Are the two options you recommended in part c closer to the median voter’s preferred option than the loser’s old position, or are they further away? So in this case, is the median voter theorem roughly true or roughly false?