Comparative Advantage

A third reason to trade is to take advantage of differences. Brazil, for example, has a climate ideally suited to growing sugar cane, China has an abundance of low-skill workers, and the United States has one of the best educated workforces in the world. Taking advantage of these differences suggests that world production can be maximized when Brazil produces sugar, China assembles iPads, and the United States devotes its efforts to designing the next generation of electronic devices.

Martha can be most productive if she does what she does most best.

Absolute advantage is the ability to produce the same good using fewer inputs than another producer.

Taking advantage of differences is even more powerful than it looks. We say that a country has an absolute advantage in production if it can produce the same good using fewer inputs than another country. But to benefit from trade, a country need not have an absolute advantage. For example, even if the United States did have the world’s best climate for growing sugar, it might still make sense for Brazil to grow sugar and for the United States to design iPads, if the United States had a bigger advantage in designing iPads than it did in growing sugar.

Here’s another example of what economists call comparative advantage. Martha Stewart doesn’t do her own ironing. Why not? Martha Stewart may, in fact, be the world’s best ironer but she is also good at running her business. If Martha spent more time ironing and less time running her business, her blouses might be pressed more precisely but that would be a small gain compared with the loss from having someone else run her business. It’s better for Martha if she specializes in running her business and then trades some of her income for other goods, such as ironing services, and of course many other goods and services as well.

The Production Possibility Frontier

A production possibilities frontier shows all the combinations of goods that a country can produce given its productivity and supply of inputs.

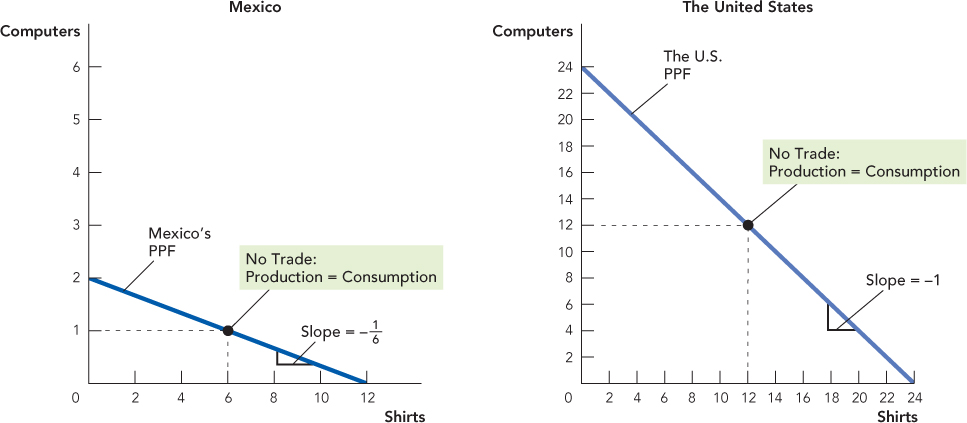

The idea of comparative advantage is subtle but important. In order to give a precise definition, let’s explore comparative advantage using a simple model. Suppose that there are just two goods, computers and shirts, and one input, labor. Assume that in Mexico, it takes 12 units of labor to make one computer and 2 units of labor to produce one shirt, and suppose that Mexico has 24 units of labor. Mexico, therefore, can produce 2 computers and 0 shirts or 0 computers and 12 shirts, or they can have any combination of computers and shirts along the line in the left panel of Figure 2.1 labeled Mexico’s PPF. Mexico’s PPF, short for Mexico’s production possibilities frontier, shows all the combinations of computers and shirts that Mexico can produce given its productivity and supply of inputs. Mexico cannot produce outside of its PPF.

Similarly, assume that there are 24 units of labor in the United States but that in the United States it takes 1 unit of labor to produce either good. The United States therefore can produce 24 computers and 0 shirts, or 0 computers and 24 shirts, or any combination along the U.S. PPF shown in the right panel of Figure 2.1.

A PPF illustrates trade-offs. If Mexico wants to produce more shirts, it must produce fewer computers, and vice versa: It moves along its PPF. That’s just another way of restating the fundamental principles of scarcity and opportunity cost.

Opportunity Costs and Comparative Advantage

In fact, there is a close connection between opportunity costs and the PPF. Looking first at the U.S. PPF in the right panel of Figure 2.1, notice that the slope, the rise over the run, is −24/24 = −1. In other words, for every additional shirt the United States produces, it must produce one fewer computer. One shirt has an opportunity cost of one computer and vice versa.

FIGURE 2.1

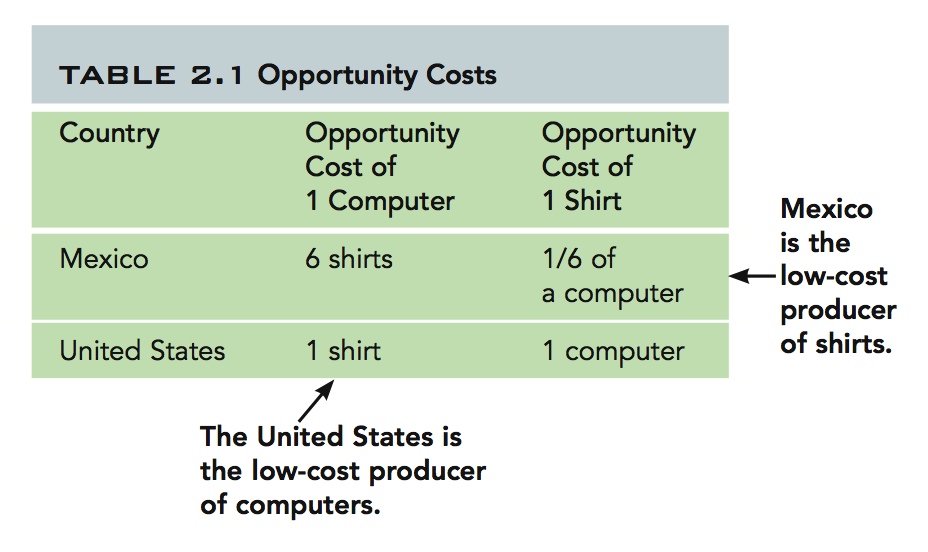

Now consider Mexico’s PPF. The rise over the run is −2/12 = −1/6. In other words, for every additional shirt that Mexico produces, it must produce 1/6th less of a computer. Once again, the slope of the PPF tells us the opportunity cost. In Mexico one shirt costs 1/6th of a computer, or 1 computer costs 6 shirts. We summarize the opportunity costs in Table 2.1.

A country has a comparative advantage in producing goods for which it has the lowest opportunity cost.

Now here is the key. The (opportunity) cost of a shirt in the United States is one computer but the (opportunity) cost of a shirt in Mexico is just one-sixth of a computer. Thus, even though Mexico is less productive than the United States, Mexico has a lower cost of producing shirts! Since Mexico has the lowest opportunity cost of producing shirts, we say that Mexico has a comparative advantage in producing shirts.

Now let’s look at the opportunity cost of producing computers. Again, the trade-off for the United States is easy to see: It can produce one additional computer by giving up one shirt so the cost of one computer is one shirt. But to produce one additional computer in Mexico requires giving up six shirts! Thus, the United States has the lowest cost of producing computers or, economists say, it has a comparative advantage in producing computers. Table 2.1 summarizes.

We now know that the United States has a high cost of producing shirts and a low cost of producing computers. For Mexico, it’s the reverse: Mexico has a low cost of producing shirts and a high cost of producing computers.

The theory of comparative advantage says that to increase its wealth, a country should produce the goods it can make at low cost and buy the goods that it can make only at high cost. Thus, the theory says the United States should make computers and buy shirts. Similarly, the theory says that Mexico should make shirts and buy computers. Let’s use some numbers and some pictures to see whether the theory holds up in our example.

Suppose that Mexico and the United States each devote 12 units of labor to producing computers and 12 units to producing shirts. We can see from the PPFs that Mexico will produce one computer and six shirts and the United States will produce 12 computers and 12 shirts. At first, there is no trade, so production in each country is equal to consumption. We show the production–consumption point of each country with a black dot in Figure 2.1. Now, can Mexico and the United States make themselves better off through trade? Yes.

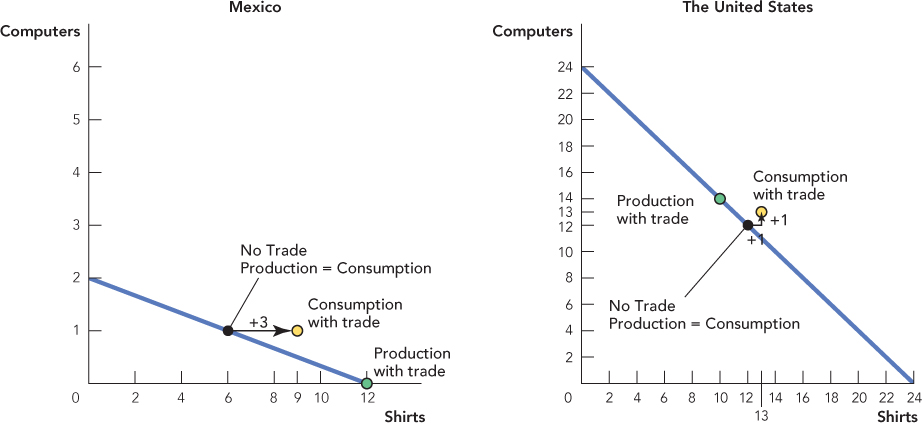

Imagine that Mexico moves 12 units of its labor out of computer production and into shirt production. Thus, Mexico specializes completely by allocating all 24 units of its labor to shirt production, thereby producing 12 shirts. Similarly, suppose that the United States moves 2 units of its labor out of shirt production and into computers—thus producing 14 computers and 10 shirts. Production in Mexico and the United States is now shown by the green points in Figure 2.2.

FIGURE 2.2

So to finish the story, can you now see a way in which both Mexico and the United States can be made better off? Sure! Imagine that the United States trades one computer to Mexico in return for three shirts. Mexico is now able to consume one computer and nine shirts (three more shirts than before trade), while the United States is able to consume 13 computers (one more than before trade) and 13 shirts (one more than before trade).

Amazingly, both Mexico and the United States can now consume outside of their PPFs. In other words, before trade, Mexico could not have consumed one computer and nine shirts because this was outside their PPF. Similarly, before trade, the United States could not have consumed 13 computers and 13 shirts. But with trade, countries are able to increase their consumption beyond the range that was possible without trade.

Thus, when each country produces according to its comparative advantage and then trades, total production and consumption increase. Importantly, both Mexico and the United States gain from trade even though the United States is more productive than Mexico at producing both computers and shirts.

The theory of comparative advantage not only explains trade patterns it also tells us something remarkable: A country (or a person) will always be the low-cost seller of some good. The reason is clear: The greater the advantage a country has in producing A, the greater the cost to it of producing B. If you are a great pianist, the cost to you of doing anything else is very high. Thus, the greater your advantages in being a pianist, the greater the incentive you have to trade with other people for other goods. It’s the same way for countries. The more productive the United States is at producing computers, the greater its demand will be to trade for shirts. Thus, countries with high productivity can always benefit by trading with lower-productivity countries, and countries with lower productivity need never fear that higher-productivity countries will outcompete them in the production of all goods.

When people fear that a country can be outcompeted in everything, they are making a common mistake, namely confusing absolute advantage with comparative advantage. A producer has an absolute advantage over another producer if it can produce more output from the same input. But what makes trade profitable is differences in comparative advantage, and a country will always have some comparative advantage.

Thus, everyone can benefit from trade. From the world’s greatest genius down to the person of below-average ability, no individuals or countries are so productive or so unproductive that they cannot benefit from inclusion in the worldwide division of labor. The theory of comparative advantage tells us something vital about world trade and about world peace. Trade unites humanity.

Comparative Advantage and Wages

Comparative advantage is a difficult story to grasp. Most of the world hasn’t got it yet so don’t be too surprised if it takes you some time as well. You may at first be bothered by the fact that we did not explicitly discuss wages. Won’t a country like the United States be uncompetitive in trade with low-wage countries like Mexico?

In fact, wages are in our model, we just need to bring them to the surface. Doing so will provide another perspective on comparative advantage.

In our model, there is only one type of labor. In a free market, all workers of the same type will earn the same wage.*; So, in this model there is just one wage in Mexico and one wage in the United States. We can calculate the wage in Mexico by summing up the total value of consumption in Mexico and dividing by the number of workers.† We can perform a similar calculation for the United States. To do this, we need only a price for computers and a price for shirts. Let’s suppose that computers sell for $300 and shirts for $100 (this is consistent with trading one computer for three shirts as we did earlier). Let’s look first at the situation with no trade (see Table 2.2). The value of Mexican consumption is 1 × $300 plus 6 × $100 for a total of $900. Since there are 24 workers, the average wage is $37.50. The value of U.S. consumption is 12 × $300 + 12 × $100 = $4,800 so the U.S. wage is $200.

TABLE 2.2 Consumption in Mexico and the United States (No Specialization or Trade)

|

Country Labor Allocation (Computers, Shirts) |

Computers |

Shirts |

|---|---|---|

|

Mexico (12, 12) |

1 |

6 |

|

United States (12, 12) |

12 |

12 |

|

Total consumption |

13 |

18 |

Now consider the situation with trade (see Table 2.3). The value of Mexican consumption is now 1 × $300 + 9 × $100 = $1,200 for a wage of $50, while the U.S. wage is now $216.67 (check it!). Wages in both countries have gone up, just as expected.

TABLE 2.3 Consumption in Mexico and the United States (Specialization and Trade)

|

Country |

Computers |

Shirts |

|---|---|---|

|

Mexico |

1 |

9 = 6 + 3 |

|

United States |

13 = 12 + 1 |

13 = 12 + 1 |

|

Total consumption |

14 |

22 |

But notice that the wage in Mexico is lower than the wage in the United States, both before and after trade. The reason is that the productivity of labor is lower in Mexico. Ultimately, it’s the productivity of labor that determines the wage rate. Specialization and trade let workers make the most of what they have—it raises wages as high as possible given productivity—but trade does not directly increase productivity.‡ Trade makes both Einstein and his less clever accountant better off, but it doesn’t make the accountant a skilled scientist like Einstein.

In summary, workers in the United States often fear trade because they think that they cannot compete with low-wage workers in other countries. Meanwhile, workers in low-wage countries fear trade because they think that they cannot compete with high-productivity countries like the United States! But differences in wages reflect differences in productivity. High-productivity countries have high wages; low-productivity countries have low wages. Trade means that workers in both countries can raise their wages to the highest levels allowed by their respective productivities.

Adam Smith on Trade

Notice that we have so far talked about trade without distinguishing it much from “international trade.” Adam Smith had an elegant summary connecting the argument for trade to that for international trade:

It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy. The tailor does not attempt to make his own shoes, but buys them of the shoemaker. The shoemaker does not attempt to make his own clothes, but employs a tailor. What is prudence in the conduct of every private family can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry employed in a way in which we have some advantage.2