Price Floors

When governments control prices, it is usually with a price ceiling designed to keep prices below market levels, but occasionally the government intervenes to keep prices above market levels. Can you think of an example? Here’s a hint. Buyers usually outnumber sellers, so it’s probably no accident that governments intervene to keep prices below market levels more often than they intervene to keep prices above market levels. The most common example of a price being controlled above market levels is the exception that proves the rule because it involves a good for which sellers outnumber buyers. Here’s another hint. You own this good.

The good is labor, and the most common example of a price that is controlled above the market level is the minimum wage.

A price floor is a minimum price allowed by law.

When the minimum price that can be legally charged is above the market price, we say that there is a price floor. Economists call it a price floor because prices cannot legally go below the floor. Price floors create four important effects:

Surpluses

Lost gains from trade (deadweight loss)

Wasteful increases in quality

A misallocation of resources

Surpluses

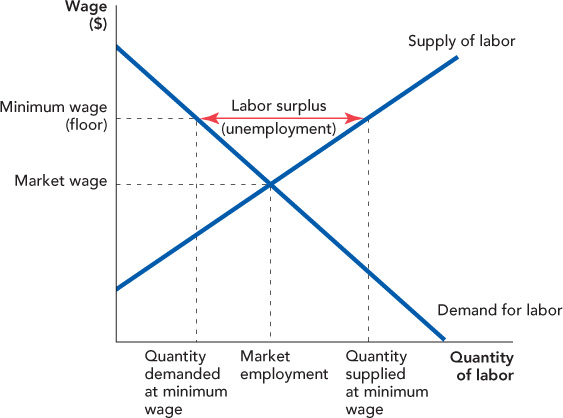

Figure 5.10 graphs the demand and supply of labor and shows how a price held above the market price creates a surplus, a situation where the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. We have a special word for a surplus of labor: unemployment.

FIGURE 5.10

The idea that a minimum wage creates unemployment should not be surprising. If the minimum wage did not create unemployment, the solution to poverty would be easy—raise minimum wages to $10, $20, or even $100 an hour! But at a high enough wage, none of us would be worth employing.

Can a more moderate minimum wage also create unemployment? Yes. A minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, the federal minimum in 2014, won’t affect most workers who, because of their productivity, already earn more than $7.25 an hour. In the United States, for example, more than 95% of all workers paid by the hour already earn more than the minimum wage. A minimum wage, however, will decrease employment among low-skilled workers. The more employers have to pay for low-skilled workers, the fewer low-skilled workers they will hire.

Young people, for example, often lack substantial skills and are more likely to be made unemployed by the minimum wage. About a quarter of all workers earning the minimum wage are teenagers (ages 16–19) and about half are less than 25 years of age.19 Studies of the minimum wage verify that the unemployment effect is concentrated among teenagers.20

In addition to creating surpluses, a price floor, just like a price ceiling, reduces the gains from trade.

Lost Gains from Trade (Deadweight Loss)

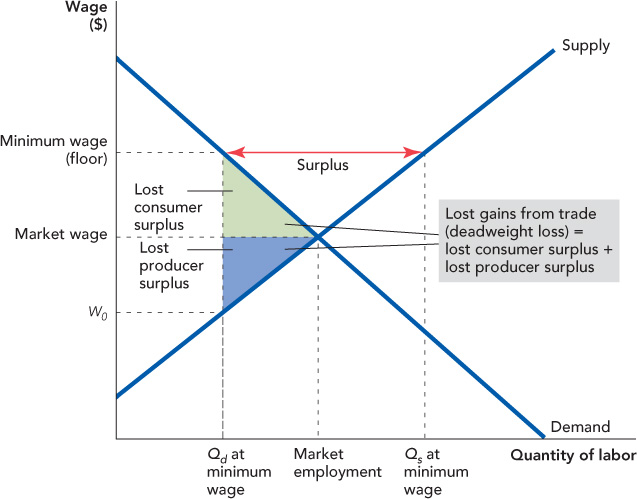

Notice in Figure 5.11 that at the minimum wage employers are willing to hire Qd workers. Employers would hire more workers if they could offer lower wages and, importantly, workers would be willing to work at lower wages if they were allowed to do so. If employers and workers could bargain freely, the wage would fall and the quantity of labor traded would increase to the level of market employment. Notice that at the market employment level, the gains from trade increase by the green and blue triangles. The green triangle is the increase in consumer surplus (remember that in this example it is the employers who are the consumers of labor) and the blue triangle is the increase in producer (worker) surplus.

FIGURE 5.11

Although the minimum wage creates some unemployment and reduces the gains from trade, the influence of the minimum wage in the American economy is very small. Even for the young, the minimum wage is not very important because although most workers earning the minimum wage are young, most young workers earn more than the minimum wage. As noted, a majority of workers earning the minimum wage are younger than 25 years old but 88% of workers younger than 25 earn more than the minimum wage.21

These facts may surprise you. The minimum wage is hotly debated in the United States. Democrats often argue that the minimum wage must be raised to help working families. Republicans respond that a higher minimum wage will create unemployment and raise prices as firms pass on higher costs to customers. Neither position is realistic. At best, the minimum wage will raise the wages of some teenagers and young workers whose wages would increase anyway as they improve their education and become more skilled. At worst, the minimum wage will raise the price of a hamburger and create unemployment among teenagers, many of whom will simply choose to stay in school longer (not necessarily a bad thing). The minimum wage debate is more about rhetoric than reality.

Even though small increases in the U.S. minimum wage won’t change much, large increases would cause serious unemployment. A large increase in the minimum wage is unlikely in the United States, but it has happened elsewhere. In 1938, Puerto Rico was surprised to discover that it was bound by a minimum wage set well above the Puerto Rican average wage for unskilled labor.

Puerto Rico has a peculiar political status; it’s an unincorporated U.S. territory classified as a commonwealth. In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which set the first U.S. minimum wage at 25 cents an hour. At the time, the average wage in the United States was 62.7 cents an hour, but in Puerto Rico many workers were earning just 3 to 4 cents an hour. Congress, however, had forgotten to create an exemption for Puerto Rico so what was a modest minimum wage in the United States was a huge increase in wages in Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rican workers, however, did not benefit from the minimum wage. Unable to pay the higher wage, Puerto Rican firms went bankrupt, creating devastating unemployment. In a panic, representatives of Puerto Rico pleaded with the U.S. Congress to create an exemption for Puerto Rico. “The medicine is too strong for the patient,” said Puerto Rican Labor Commissioner Prudencio Rivera Martinez. Two years later Congress finally did establish lower rates for Puerto Rico.22

Keep in mind that there are substitutes for minimum wage workers. Higher minimum wages, for example, increase the incentive to move production to other cities, states, or countries where wages are lower. The United States imports lots of fruits and vegetables because it is cheaper to produce these abroad and ship them to the United States than it is to produce them here. Many minimum wage jobs are service jobs that cannot be moved abroad but firms can substitute capital—in the form of machines—for labor. If the minimum wage were to increase substantially, we might even see robots flipping burgers.

To explain the other important effects of price floors—wasteful increases in quality and a misallocation of resources—we turn from minimum wages to airline regulation.

Wasteful Increases in Quality

Many years ago, flying on an airplane was pleasurable; seats were wide, service was attentive, flights weren’t packed, and the food was good. So airplane travel in the United States must have gotten worse, right? No, it has gotten better. Let’s explain.

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) extensively regulated airlines in the United States from 1938 to 1978. No firm could enter or exit the market, change prices, or alter routes without permission from the CAB. The CAB kept prices well above market levels, sometimes even denying requests by firms to lower prices!

We know that prices were kept above market levels because the CAB only had the right to control airlines operating between states. In-state airlines were largely unregulated. Using data from large states like Texas and California, it was possible to compare prices on unregulated flights to prices on regulated flights of the same distance. Prices on flights between San Francisco and Los Angeles, for example, were half the price of similar-length flights between Boston and Washington, D.C.

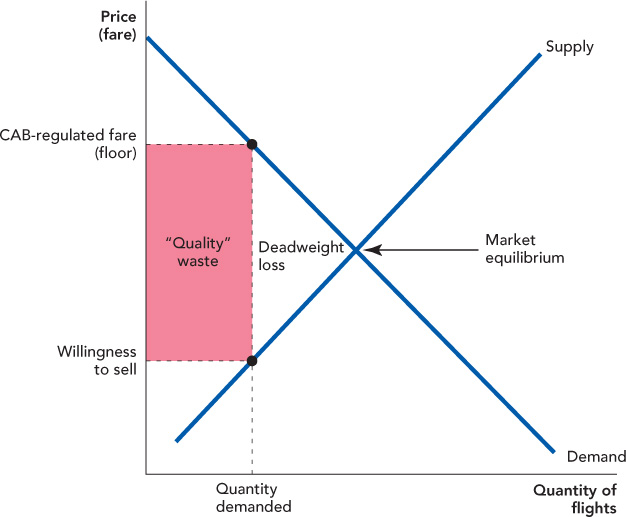

In Figure 5.12, firms are earning the CAB-regulated fare on flights that they would be willing to sell at the much lower price labeled “Willingness to sell.” Initially, therefore, regulation was a great deal for the airlines, who took home the red area as producer surplus.

FIGURE 5.12

A price floor means that prices are held above market levels, so firms want more customers. The price floor, however, makes it illegal to compete for more customers by lowering prices. So how do firms compete when they cannot lower prices? Price floors cause firms to compete by offering customers higher quality.

When airlines were regulated, for example, they competed by offering their customers bone china, fancy meals, wide seats, and frequent flights. Sounds good, right? Yes, but don’t forget that the increase in quality came at a price. Would you rather have a fine meal on your flight to Paris or a modest meal and more money to spend at a real Parisian restaurant?

If consumers were willing to pay for fine meals on an airplane, airlines would offer that service. But if you have flown recently, you know that consumers would rather have a lower price. An increase in quality that consumers are not willing to pay for is a wasteful increase in quality. Thus, as firms competed by offering higher quality, the initial producer surplus was wasted away in frills that consumers liked but would not be willing to pay for—hence, the red area in Figure 5.12 is labeled “‘Quality’ waste.”

Airline costs increased over time for another reason. The producer surplus initially earned by the airlines was a tempting target for unions who threatened to strike unless they got their share of the proceeds. The airlines didn’t put up too much of a fight because, when their costs rose, they could apply to the CAB for an increase in fares, thus passing along the higher costs to consumers. Many of the problems that older airlines have faced in recent times are due to generous pension and health benefits, which were granted when prices of flights were regulated above market levels.

By 1978, costs had increased so much that the airlines were no longer benefiting from regulation and were willing to accede to deregulation.23 Deregulation lowered prices, increased quantity, and reduced wasteful quality competition.24 Deregulation also reduced waste and increased efficiency in another way—by improving the allocation of resources.

The Misallocation of Resources

Regulation of airline fares could not have been maintained for 40 years if the CAB had not also regulated entry. Firms wanted to enter the airline industry because the CAB kept prices high, but the CAB knew that if entry occurred, prices would be pushed down. So under the influence of the older airlines, the CAB routinely prevented new competitors from entering. In 1938, for example, there were 16 major airlines; by 1974, there were just 10 despite 79 requests to enter the industry.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 5.7

The European Union guarantees its farmers that the price of butter will stay above a floor. The floor price is often above the market equilibrium price. What do you think has been the result of this?

The European Union guarantees its farmers that the price of butter will stay above a floor. The floor price is often above the market equilibrium price. What do you think has been the result of this?

Question 5.8

The United States has set a price floor for milk above the equilibrium price. Has this led to shortages or surpluses? How do you think the U.S. government has dealt with this? (Hint: Remember the cartons of milk you had in elementary school and high school? What was their price?)

The United States has set a price floor for milk above the equilibrium price. Has this led to shortages or surpluses? How do you think the U.S. government has dealt with this? (Hint: Remember the cartons of milk you had in elementary school and high school? What was their price?)

Restrictions on entry misallocated resources because low-cost airlines were kept out of the industry. Southwest Airlines, for example, began as a Texas-only airline because it could not get a license from the CAB to operate between states. (Lawsuits from competitors also nearly prevented Southwest from operating in Texas.) Southwest was able to enter the national market only after deregulation in 1978.

The entry of Southwest was not just a case of increasing supply. One of the virtues of the market process is that it is open to new ideas, innovations, and experiments. Southwest, for example, pioneered consistent use of the same aircraft to lower maintenance costs, greater use of smaller airports like Chicago’s Midway, and long-term hedging of fuel costs. Southwest’s innovations have made it one of the most profitable and largest airlines in the United States. Southwest’s innovations have spread, in turn, to other firms such as JetBlue Airways, easyJet (Europe), and WestJet (Canada). Regulation of entry didn’t just increase prices; it increased costs and reduced innovation. Deregulation improved the allocation of resources by allowing low-cost, innovative firms to expand nationally. Deregulation is the major reason why, today, flying is an ordinary event for most American families, rather than the province of the wealthy.