Problems with GDP as a Measure of Output and Welfare

GDP measures the market value of final goods and services. But we do not know the market value of many goods and services. We don’t know the market value, for example, of illegally produced goods and services because neither the buyers nor the sellers are willing to answer questions from government statisticians. An even more serious problem is that we don’t know the market value of goods and service that are not bought and sold in markets. We don’t know, for example, the market value of clean air because clean air is not bought and sold in a market.

Let’s look in more detail at some examples of each of these problems.

GDP Does Not Count the Underground Economy

Illegal or underground-market transactions are omitted from GDP. Sales of crack cocaine, for example, or sales of counterfeit DVDs are not reported and so do not show up in government statistics. Legal goods sold “under the table” to avoid taxes also do not show up in GDP.

Nations that have greater levels of corruption and higher tax rates usually have higher levels of underground transactions. In Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, it takes an estimated 203 days of fighting the bureaucracy to start and register a legal business.4 It is no wonder that so many Haitians keep their commercial activity outside the law. More generally, the size of the informal or “outside the law” sector in Latin America is estimated at 41% of officially measured GDP.5

Nations with a great deal of illegal and off-the-books activity are not as poor as they appear in the official GDP statistics. In the United States or Western Europe, the underground economy is likely between 10% and 20% of GDP; that percentage is small relative to the percentage in Haiti or most of Latin America but in absolute terms it is still quite large.

GDP Does Not Count Nonpriced Production

Nonpriced production occurs when valuable goods and services are produced but no explicit monetary payment is made. If a son mows his parent’s lawn, the service will not be included in GDP. If a lawn care firm provided the identical work, it would be included in GDP. Yet either way the grass gets cut and economic output increases. Similarly, if you watch videos for free on YouTube, this is not counted in GDP, but if you buy a ticket to the movie theater it is counted in GDP. People search for valuable information on Google, read blogs and newspapers online, and chat with their friends on Facebook but these transactions are not registered in the GDP statistics since they are not priced. Volunteering of all kinds, such as when church workers deliver food to the elderly, people pick up garbage in parks, and book reviewers post reviews on Amazon, is also not counted in GDP. Each of these activities adds to economic output but if the transaction isn’t priced, it isn’t counted in the GDP statistics.

The omission of nonpriced production introduces two biases into GDP statistics: biases over time and biases across nations.

In the United States, the portion of women who are in the official labor force has almost doubled since 1950, rising from 34% to about 60% today. As a result, mothers spend less time working at home than in 1950, but there are more nannies and house cleaners in the economy today. The mothers who worked at home in 1950 were not paid and their valuable services were not counted in GDP. Nannies and house cleaners today are paid and their services are counted in GDP (unless the nanny is hired “under the table” to avoid paying Social Security taxes, of course!). The result is that U.S. GDP in 1950 underestimates a little the real production of goods and services in 1950 relative to that of today.

Nonpriced production also affects GDP comparisons across countries. For example, many cultures discourage women from becoming part of the official workforce. In India, women make up only 28% of the labor force, compared with 46% for the U.S.6 The output of the other 72% of Indian women is not included in Indian GDP but these women are working. Indian GDP statistics, therefore, underestimate the real production of goods and services in India.

Household production is especially important in poor countries and in rural areas. It is common to read of families, say, in rural Mexico, that earn no more than $1,000 a year. Living off this sum sounds impossible to a contemporary American, but keep in mind that many of these families build their own homes (with help from relatives and friends), grow their own food, and sew their own clothes. Their lives are hard, but much of what they produce is not captured in GDP statistics.

GDP Does Not Count Leisure

Leisure, or time spent not working, is also omitted from GDP statistics. People value leisure, just as they value food and transportation. But when people consume food and transportation, measured GDP increases. When people consume more leisure, however, measured GDP does not rise and, in fact, it will fall if we are not at work. Of course, for some forms of leisure we must make purchases like fishing rods and campers, which are counted in GDP, but it’s difficult to measure the true value of leisure.

In the United States, the average workweek has fallen by 10% since 1964 (from 38 hours to about 34.5 hours per week). Moreover, work at home has also declined as washing machines, microwaves, and vacuum cleaners have made work at home easier and less time-consuming. This growth in leisure time is an improvement in human well-being but is not reflected in GDP.

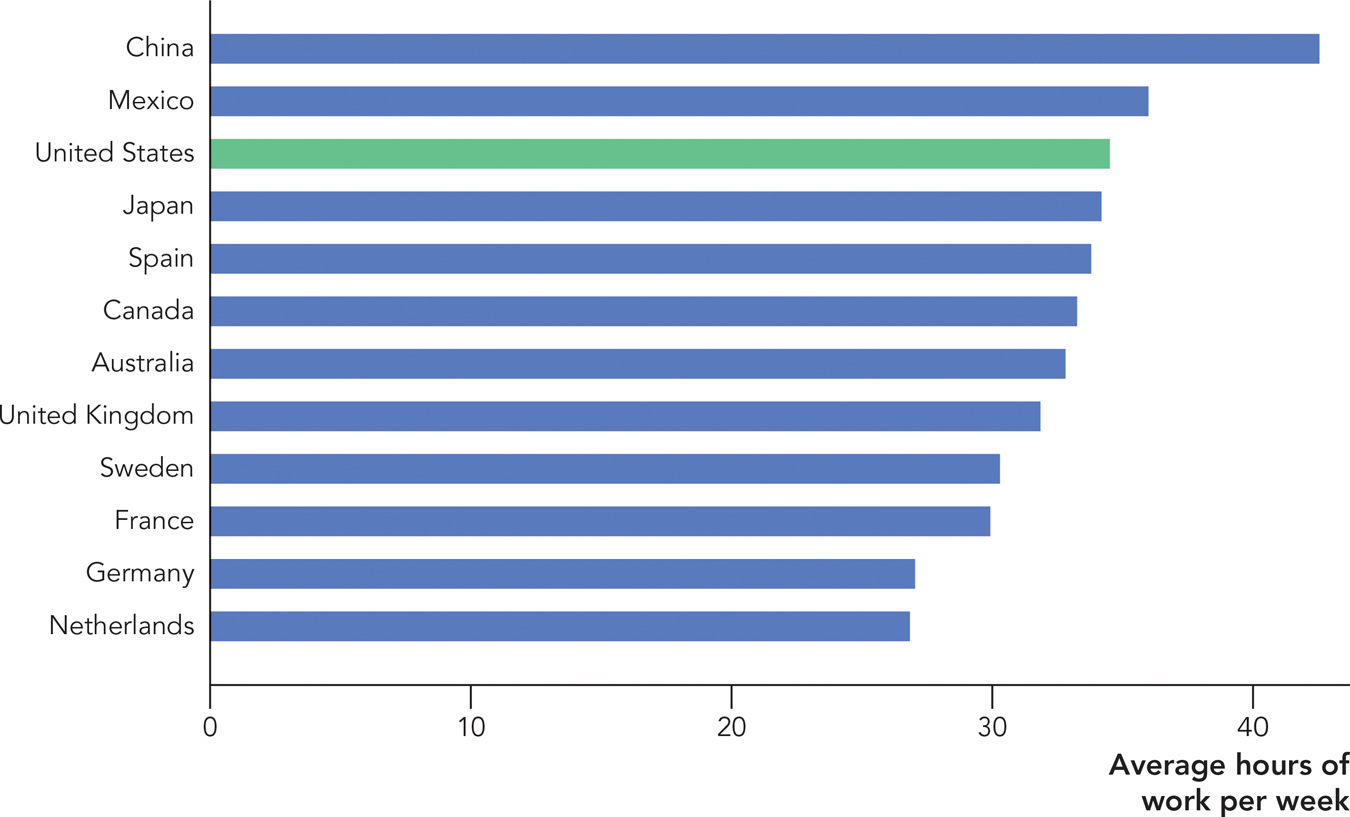

While the average workweek in the United States has fallen, it has dropped much farther in some other nations. Figure 6.7 shows the average number of hours worked per week in a selection of nations. While the workweek in the United States is down to about 34.5 hours, individuals in other developed nations such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom work less. In the Netherlands, the average workweek is only 27 hours per week! Since leisure time is not added to GDP, the longer workweek will make the United States look better off compared with Europe than is actually the case. Note, however, that although the workweek in the United States is long compared with that of other developed countries, the workweek is even longer in many poorer countries. In China, for example, the average workweek is about 42.5 hours.

FIGURE 6.7

Source: OECD Statistics, 2006, and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

GDP Does Not Count Bads: Environmental Costs

GDP adds up the market value of final goods and services but does not subtract the value of bads. Pollution, for example, is a bad that is produced every year, but this bad is not counted in the GDP statistics. GDP statistics also do not count the destruction of water aquifers, the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, or changing supplies of natural resources. Similarly, GDP statistics do not count the loss of animal or plant species as economic costs, unless those animals and plants had a direct commercial role in the economy. Other bads are also not counted in GDP. The bad of crime, for example, is not counted in the GDP statistics.

Since more pollution isn’t counted as a bad, it’s not surprising that less pollution is also not counted as a good. America has cleaner air and cleaner water than it did in 1960, but GDP statistics do not reflect this improvement.

The movement for “green accounting” has tried to reform GDP statistics to cover the environment more explicitly. Most economists agree with the logic behind green accounting: GDP should measure the market value of all final goods and services even if those goods and services are not traded in markets. They also acknowledge other attempts to improve GDP statistics to take into account nonpriced production, leisure, crime, and so forth but most of these problems are very difficult to solve. Environmental amenities, for example, are difficult to value. How much, for instance, should be added to GDP because polar bears are present in Alaska? How much is a glacier worth? A coral reef? Estimates of the values of these resources may be computed for individual problems, but when it comes to the economy as a whole, the measurement task seems insurmountable. Rather than introduce so much uncertainty into the entire GDP concept, economists usually restrict green accounting (and other GDP modifications) to the analysis of particular problems.

GDP Does Not Measure the Distribution of Income

GDP per capita is a rough measure of the standard of living in a country. But if GDP per capita grows by 10%, this does not necessarily mean that everyone’s income grows by 10% or even that the average person’s income grows by 10%.

To see why, imagine that we have a country of four people, John, Paul, George, and Ringo, whose factor incomes in year 1 are 10, 20, 30, and 40. Using the factor income approach, we know that GDP is 100 (10 + 20 + 30 + 40) and thus GDP per capita is 25 (100/4). GDP in year 1 and its distribution are shown in the first row of Table 6.3.

TABLE 6.3 Growth in GDP per Capita Can Be Distributed in Different Ways

|

|

John |

Paul |

George |

Ringo |

GDP |

GDP per Capita |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year 1 |

10 |

20 |

30 |

40 |

100 |

25 |

|

(a) Year 2 |

11 |

22 |

33 |

44 |

110 |

27.5 |

|

(b) Year 2 |

10 |

20 |

30 |

50 |

110 |

27.5 |

|

(c) Year 2 |

20 |

20 |

30 |

40 |

110 |

27.5 |

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 6.13

Why does GDP not account for or try to measure certain things? What is the common thread throughout all of the uncounted variables?

Why does GDP not account for or try to measure certain things? What is the common thread throughout all of the uncounted variables?

Question 6.14

If two countries have the same GDP per capita, do they necessarily have the same level of inequality?

If two countries have the same GDP per capita, do they necessarily have the same level of inequality?

Question 6.15

If GDP does not account for everything, does that make the GDP statistic useless?

If GDP does not account for everything, does that make the GDP statistic useless?

Now suppose that in year 2 GDP grows by 10% to 110 and thus GDP per capita grows to 27.5 (110/4). This growth in GDP, however, is consistent with any of the three outcomes shown in rows a, b, and c of Table 6.3. In row a, everyone’s income grows by 10%—so John’s income grows from 10 to 11, Paul’s income grows from 20 to 22, and so forth. In row b, the growth in GDP is concentrated on Ringo, the richest person: His income grows by 25% (from 40 to 50) and everyone else’s income stays the same. In row c, the growth in GDP is concentrated on John, the poorest person. His income grows by 100% (from 10 to 20) and everyone else’s income stays the same.

GDP and GDP per capita grow by the same amount in each of these cases, but in row a inequality stays the same, in row b inequality increases, and in row c inequality decreases.

In most countries most of the time, growth in GDP per capita is like row a: Everyone’s income grows by approximately the same amount.7 Thus, growth in real GDP per capita usually does tell us roughly how the average person’s standard of living is changing over time. In examining particular countries and periods, however, we might want to look more carefully at how growth in GDP is distributed. In other words, GDP figures are useful but they will always be imperfect.