CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 10.7

1. Let’s sort the following eight items into private costs, external costs, private benefits, or external benefits. There’s only one correct answer for each of questions a–h.

The price you pay for an iTunes download

The benefit your neighbor receives from hearing you play your pleasant music

The annoyance of your neighbor because she doesn’t like your achingly conventional music

The pleasure you receive from listening to your iTunes download

The price you pay for a security system for your home

The safety you enjoy as a result of having the security system

The crime that is more likely to occur to your neighbor once a criminal sees a “Protected by alarm” sticker on your window

The extra safety your neighbor might experience because criminals tend to stay away from neighborhoods that have a lot of burglar alarms

Question 10.8

2. If the students at your school started saying “thank you” to friends who got flu shots, would this tend to reduce the undersupply of people who get flu shots? Why or why not?

Question 10.9

3.

Consider a factory, located in the middle of nowhere, producing a nasty smell. As long as no one is around to experience the unpleasant odor, are any externalities produced?

Suppose that a family moves in next door to the smelly factory. Do we now have an externalities problem? If so, who is causing it: the factory by producing the smell, the family by moving in next door, or both?

Page 191Suppose that the family clearly possesses the right to a pleasant-smelling environment. Does this mean that the factory will be required to stop producing the bad smell? What could happen instead? There are many right answers. (Hint: Think about the Coase theorem. Actually, it’s always a good idea to think about the Coase theorem, whether the topic is smelly factories, labor–management disputes, international peace negotiations, or divorce settlements.)

Question 10.10

4. Considering what we’ve learned about externalities, should human-caused global warming be completely stopped? Explain, using the language of social benefits and social costs.

Question 10.11

5. In the following cases, the markets are in equilibrium, but there are externalities. In each case, determine whether there is an external benefit or cost and estimate its size. Finally, decide between a tax or a subsidy as a simple way to compensate for the externality. Fill out the table below with your answers.

In the market for automobiles, the private benefit of one more small SUV is $20,000 and the social cost of one more small SUV is $30,000.

In the market for fashionable clothes, the marginal social benefit of one more dress per person is $100, and the marginal private benefit is $500. Bonus: Can you tell an externality story that makes sense of these numbers?

In the market for really good ideas, ideas that will dramatically change the world for the better, the private benefit of one more really good idea (from speaker’s fees, book sales, patents, etc.) is $1 million. The marginal social benefit is $1 billion.

|

Case |

External Cost or Benefit? |

Size of External Benefit (or Cost if Negative) |

Tax It or Subsidize It? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

a. SUVs |

|

|

|

|

b. Fashionable clothes |

|

|

|

|

c. Ideas |

|

|

|

Question 10.12

6. In which cases are the Coase theorem’s assumptions likely to be true? In other words, when will the parties be likely to strike an efficient bargain? How do you know?

My neighbor wants me to cut down an ugly shrub in my front yard. The ugly shrub, of course, imposes an external cost on him and on his property value.

My neighbors all would love for me to get that broken-down Willys Jeep off my front lawn. It’s been years now, after all. And would it be too much for me to paint the house and fill up that 6-foot deep ditch in the front yard? The whole neighborhood is annoyed.

A coal-fired electricity plant dumps its leftover hot water into the nearby lake, killing the naturally occurring fish. Thousands of homes line the banks of the lake.

A coal-fired electricity plant dumps its leftover hot water into the nearby river, killing the naturally occurring fish downstream. There is one large fishery 1 mile downstream affected by this. After that, the water cools enough so it’s not a problem.

Question 10.13

7. With electricity, we saw that it was important to tax the pollutant rather than the final product itself. In the following cases, will the proposed taxes actually hit at the source of the external cost, or will it only land an inefficient glancing blow? What kind of tax might be better?

Gas-guzzling cars create more pollution, so the government should tax big SUVs at a higher rate.

All-night liquor stores seem to generate unruly behavior in nearby neighborhoods, so owners of all-night liquor stores should pay higher property taxes.

Page 192Bell-bottom jeans insist on coming back every few years, and their ugliness creates external costs for all who see them. Therefore, bell-bottom jeans should be taxed heavily.

American parents are worried about their children hearing too much profanity on television. Congress decides to tax TV shows based on the number of profane words used on the shows.

Question 10.14

8. When the government expands the number of pollution allowances, does that increase the cost of polluting or cut it? What about when the number of pollution allowances is cut back?

Question 10.15

9. Maxicon is opening a new coal-fired power plant, but the government wants to keep pollution down.

Based on what we’ve seen in this chapter, which is a more efficient way to reduce pollution: commanding Maxicon to use one particular air-scrubbing technology that will reduce pollution by 25% or commanding Maxicon to reduce pollution by 25%?

If a corrupt government just grants Maxicon all of the (tradable) pollution permits in the entire nation (even though there are many energy companies), does this guarantee that Maxicon will engage in an enormous amount of pollution? Why or why not?

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 10.16

1. When someone is sick, the patient’s decision to take an antibiotic imposes costs on others—it helps bacteria evolve resistance faster. But it also gives free benefits to others: It may slow down the spread of infectious disease the same way that vaccinations do. Thus, antibiotics can create external costs as well as external benefits. In theory, these could cancel each other out, so that just the right amount of antibiotics is being used. But economists think that on balance, there is overuse of antibiotics, not underuse. Why? (Hint: Think on the margin!)

Question 10.17

2. A flu shot typically costs about $25–$50 but some firms offer their employees free flu shots. Why might a firm prefer to offer its employees free flu shots if the alternative is an equally costly wage increase?

Question 10.18

3. “The environment is priceless.” What evidence do you have that this statement is incorrect?

Question 10.19

4. Cultural influences often create externalities, for good and ill. A happy movie might make people smile more, which improves the lives of people who don’t see the movie. A fashion trend for tight-fitting clothing might hurt the body image of people who think they won’t look good in the trendy clothing.

Let’s consider the market for one cultural good that unrealistically raises expectations about the opposite sex: the romance novel. In romance novels, men are dangerous yet safe, they are wealthy yet never at work, they ride high-speed motorcycles yet never get in terrible accidents, they look fantastic even though they never waste endless hours at the gym, and so on. (Of course, advertising that focuses on sexy female models may also unrealistically raise expectations about the opposite sex so feel free to change our example as you see best.)

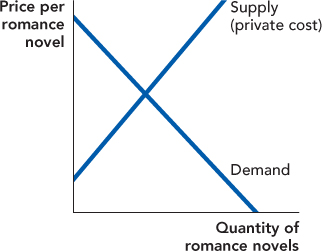

Consider the following market. Romance novels impose an external cost on men, who have to try to live up to these unrealistic expectations. Illustrate the effect of this external cost in the figure.

Illustrate in the figure the deadweight loss from the externality, before a tax or other solution is imposed.

If the government decides to compensate for the externality by imposing a tax on romance novels, should the tax be high enough to stop everyone from reading the novels? Why or why not?

Show graphically how big the tax should be per novel.

As long as the government spends the money efficiently, does it matter what the government spends the money from the “romance novel tax” on? In other words, could the government just use the money to pay for necessary roads and bridges, or does it need to spend the money to fix the harmful social effects of romance novels?

Page 193

Question 10.20

5. Green Pastures Apartments wants to build a playground to increase demand for its larger-sized apartments but is worried that it will be overcrowded with tenants from the Still Waters Mobile Estates and Twin Pines Townhomes developments nearby.

What type of externality is the playground: external cost or external benefit?

What type of compromise might Green Pastures be able to make with Still Waters and Twin Pines so that all three developments will benefit from the playground? More than one answer is possible, but give just one based on reasoning from this chapter.

Question 10.21

6. In Chapter 6, we said that taxes create deadweight losses. When we tax goods with external costs, should we worry about deadweight losses? Why or why not?

Question 10.22

7. Economists have found that increasing the proportion of girls in primary and secondary school leads to significant improvement in students’ cognitive outcomes (Victor Lavy and Analia Schlosser. 2007. Mechanisms and impacts of gender peer effects at school, NBER Working Paper 13292). One key channel seems to be that, on average, boys create more trouble in class, which makes it harder for everyone to learn. In newspaper English, we’d say that “boys are a tax on every child’s education.”

Using the tools of this chapter, do girls in a classroom provide external costs or benefits? What about boys?

Just based on this study, if you are a parent of a boy, would you rather your son be in a class with mostly boys or mostly girls? What if you are the parent of a girl?

Who should be taxed in this situation? Can you see any problems implementing this tax?

Question 10.23

8. In the example of honeybees, we said that the farmers pay the beekeepers for pollination services. But why don’t the beekeepers pay the fruit farmers? After all, the beekeepers need the fruit farmers to make honey, so why does the payment go one way and not the other? (Hint: What if the honey produced by some fruits and vegetables such as almonds is bitter?)

Question 10.24

9. A government is deciding between command and control solutions versus tax and subsidy solutions to solve an externality problem. In each case, explain why you think one is better, using arguments from the chapter.

Suppose that whales are threatened with extinction because a large number of people like to eat whale meat. Governments are torn between banning all whaling except for certain religious ceremonies and heavily taxing all whale meat. Assume that only a few countries in the world consume whale meat, and that they have fairly efficient governments.

Fires create external costs because they spread from one building to another. Should governments encourage subsidies to sprinkler systems or should they just mandate that everyone have sprinklers?

Pets who procreate can create external costs due to problems with stray animals. Strays are extremely common on the streets of poor countries. Sterilization can solve the problem, but is a tax/subsidy or command and control a better method to encourage sterilization? Does the best solution depend on the sex of the animal?

CHALLENGES

Question 10.25

1. Before Coase presented his theorem, economists who wanted economic efficiency argued that people should be responsible for the damage they do—they should pay for the social costs of their actions. This advice fits nicely with notions of personal responsibility. Explain how the Coase theorem refutes this older argument.

Question 10.26

2. A government is torn between selling annual pollution allowances and setting an annual pollution tax. Unlike in the messy real world, this government is quite certain that it can achieve the same price and quantity either way. It wants to choose the method that will pull in more government tax revenue. Is selling allowances better for revenues or is setting a pollution tax better, or will both raise exactly the same amount of revenue? (Hint: Recall that tax revenue is a rectangle. Compare the size of the tax rectangle in Figure 10.5 with the most someone will pay for the right to pollute at the efficient level.)

Question 10.27

3. Palm Springs, California, was once the playground of the rich and famous—for example, the town has a Frank Sinatra Drive, a Bob Hope Drive, and a Bing Crosby Drive. The city once had a law against building any structure that could cast a shadow on anyone else’s property between 9 AM and 3 PM (Source: Armen Alchian and William Allen. 1964. University Economics, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth). What are some alternatives to this command and control solution? Are they any better than this approach?

Question 10.28

4. At indoor shopping malls, who makes sure that no business plays music too loud, that no store is closed too often, and that the common areas aren’t polluted with garbage? What incentive does this party have to prevent these externalities? Does your answer help explain why parents are quite happy to let their preteen and teen children stroll the malls, as in the Kevin Smith movie Mallrats?

WORK IT OUT

A local town is under pressure from voters to close a polluting factory. The head of the homeowner’s organization argues that the pollution is a menace, and if the full external costs of the pollution were included, the factory would be unprofitable. The homeowners calculate that the pollution generates an external cost of $3,000,000 per year in medical bills and $1,000,000 per year in suppressed property values (the difference in home prices with and without the pollution). The factory, on its books, makes a profit of $5,000,000 per year.

What is the external cost of the pollution?

If the factory is forced to consider the total social costs of pollution, would it be profitable?

How much could the town tax the factory before profits became zero?

What does the Coase theorem suggest about negotiations between the town and the factory?