What Price to Set?

The first of these questions—what price should a firm set?—is the easiest to answer because under some conditions, the firm doesn’t set prices; it simply accepts the price that is given by the market. So, let’s start with the pricing decision.

If the price of oil is $50 per barrel, will you be able to sell your oil for $100 a barrel? Of course not. Oil is pretty much the same wherever it is found in the world (this is not quite true but it’s close enough for our purposes), so even your mother probably won’t pay much extra just because it’s your oil. Thus, you can’t charge appreciably more than $50 a barrel. What about charging a lower price? You could charge less but why would you? The world market for oil is so large that you can easily sell all that you can produce at the market price. Thus, your pricing decision is easy; you can’t sell any oil at a price above the market price and you can sell all your oil at the market price. Thus to maximize profit, you sell at the market price.

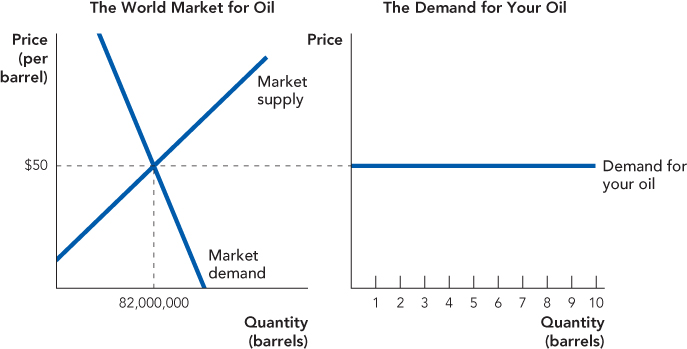

To better understand this result, let’s recall an insight about the elasticity of demand from Chapter 5: The more and the better the substitutes, the more elastic the demand. With more than 400,000 oil wells in the United States alone, the substitutes for oil from your well are so plentiful that a useful approximation is to think of the demand for your oil as perfectly elastic (flat) at the world price. In Figure 11.1, we compare the world market for oil on the left with the demand for your oil on the right.

FIGURE 11.1

The price of oil is determined in the world market, where approximately 82 million barrels are bought and sold every day. Your stripper well, however, can at best produce a tiny fraction of world demand, perhaps 10 barrels of oil per day. As a result, the world price of oil won’t change by a noticeable amount whether you produce 2, 7, or 10 barrels of oil a day.* This is why in the right panel of Figure 11.1, we draw the demand curve for your oil as flat at the market price—whether you choose to sell 2, 7, or 10 barrels, the price is the same: $50 per barrel.

Your job as an entrepreneur is greatly simplified if you don’t have to decide on the price, and so is our job as economists trying to understand firm behavior. Thus, in this chapter, we are going to simplify by assuming that the demand for a firm’s product is perfectly elastic at the market price.

A stripper well doesn’t have much influence on the price of oil because there’s nothing special about oil from a particular producer, and there are many buyers and sellers of oil, each small relative to the total market. Generalizing, a perfectly elastic demand curve for firm output is a reasonable approximation when the product being sold is similar across different firms and there are many buyers and sellers, each small relative to the total market. The markets for gold, wheat, paper, steel, lumber, cotton, sugar, vinyl, milk, trucking, glass, Internet domain name registration, and many other goods and services satisfy these conditions.

The long run is the time after all exit or entry has occurred.

In addition, don’t forget another lesson from Chapter 5: Demand curves are more elastic in the long run. We define the long run as the time after all exit and entry has occurred, and the short run as the period before exit and entry can occur. Imagine that you are the owner of the only grocery store in a small town. Can you raise prices to exorbitant levels, reasoning that everyone needs food and you are the only seller? In the short run, you probably could. But if you raise prices too high, other sellers will set up shop and your business will be wiped out. Thus, even when there aren’t many sellers, there are sometimes many potential sellers so a perfectly elastic demand curve can be a reasonable assumption even in a market with a few firms, at least in the long run.

The short run is the period before exit or entry can occur.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 11.1

In a competitive market, what happens when a firm prices its product above the market price? Below the market price?

In a competitive market, what happens when a firm prices its product above the market price? Below the market price?

Question 11.2

What kind of demand elasticity curve does the competitive firm face?

What kind of demand elasticity curve does the competitive firm face?

Question 11.3

How can a firm that produces oil face a very elastic demand curve when the demand for oil is inelastic?

How can a firm that produces oil face a very elastic demand curve when the demand for oil is inelastic?

Summarizing, economists say that an industry is competitive (or sometimes “perfectly competitive”) when firms don’t have much influence over the price of their product. This is a reasonable assumption under at least the following conditions:

The product being sold is similar across sellers.

The product being sold is similar across sellers.

There are many buyers and sellers, each small relative to the total market. and/or

There are many buyers and sellers, each small relative to the total market. and/or

There are many potential sellers.

There are many potential sellers.

When do firms have a lot of influence on the price of their product? Briefly, for purposes of comparison, a firm selling a product for which there are neither many other sellers nor potential sellers has considerable freedom to choose its price. We will analyze how firms choose price and output under these conditions in Chapter 13 through Chapter 17.

A competitive firm will sell its output at the market price, but what quantity will it choose to produce?