Entry, Exit, and Shutdown Decisions

Firms seek profits so in the long run firms will enter an industry when P > AC and exit an industry when P < AC. Notice that at the intermediate point, when P = AC, profits are zero and there is neither entry nor exit.

In Figure 11.5, we can see that at a price of $4, the firm is taking losses. Thus, in the long run, this firm will exit the industry. In fact, at any price below $17, the firm will be making a loss at any output level. Thus at any price below $17, the firm will exit the industry in the long run. At any price above $17, firms will be making profits and other firms will enter the industry.

Zero profits or normal profits occur when P = AC. At this price the firm is covering all of its costs, including enough to pay labor and capital their ordinary opportunity costs.

Only when P = AC, in this case when P = $17, will firms be making zero profits, and there will be no incentive to either enter or exit the industry. Students often wonder why firms would remain in an industry when profits are zero. The problem is the language of economics. By zero profits, economists mean what everyone else means by normal profits. Remember that average cost includes wages and payments to capital, so even when the firm earns “zero profits,” labor and capital are being paid enough to keep them in the industry. Thus, when we say that a firm is earning zero profits, we mean that the price of output is just enough to pay labor and capital their ordinary opportunity costs.

The Short-Run Shutdown Decision

If P < AC, the firm is making a loss so it wants to exit the industry but exit typically cannot occur immediately. Remember our stripper oil well and how it rents the land from which it pumps the oil? We said the rent was $30 per day but that doesn’t mean the firm can stop paying rent immediately. Rent contracts, for example, often require that the renter give 30 days’ notice. So suppose that the firm gives notice to the landowner that in 30 days it will exit and stop paying rent. What does the firm do for the next 30 days? Should it shut down and produce nothing or should it continue to produce something even though it is taking a loss?

If the well shuts down immediately, the firm will lose $30 per day for 30 days. On the other hand, if the price of oil is, say, $11 and if the firm produces 3 barrels of oil (the profit-maximizing amount when P = $11; see the chart in Figure 11.4), then the firm will have daily revenues of $33 and daily costs of $51 ($30 rent plus $21 in variable cost; see chart in Figure 11.4) for a total daily loss of $18 ($33 – $51). A daily loss of $18 isn’t good—that is why the firm wants to exit—but it’s better than a daily loss of $30. In other words, by not shutting down, the firm is able to cover all of its variable costs and some of its fixed costs (the rent), and that is better than producing nothing and paying the rent.

As usual in economics we can also show this insight with another curve! The firm is taking a loss when:

TR < TC

Recall that when we divide both sides of this equation by Q, we get our condition for long-run exit, P < AC. To understand the firm’s optimal short-run shutdown decision we are going to do something very similar. Total cost can be broken down into fixed costs and variable costs.

TC = FC + VC

But in the short run the firm has no choice about its fixed costs; it has to pay the fixed costs no matter how much output the firm produces. Since choice doesn’t influence the fixed costs, the fixed costs should not influence choice. In the short run, the fixed costs are an expense but not an economic (opportunity) cost so they should be ignored. Thus, the firm should shut down immediately only if TR < VC, or dividing both sides by Q as before, the firm should shut down immediately only if

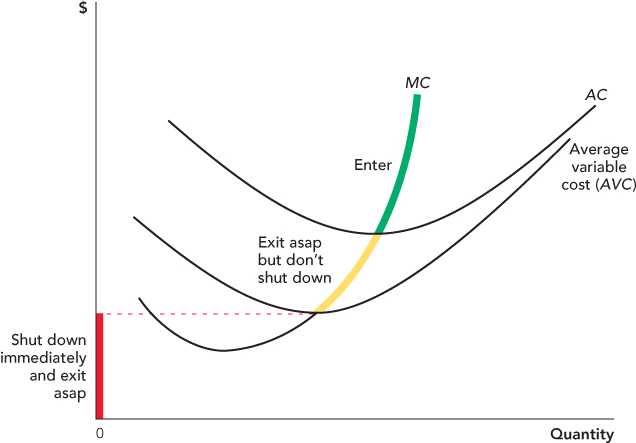

We call  the average variable cost curve, or AVC, and give an example in Figure 11.6. The AVC curve has a very similar shape to the AC curve and it gets closer and closer to the AC curve as Q increases. (Why? This is a good question to test your knowledge—see Thinking Problem 15 at the end of this chapter.)

the average variable cost curve, or AVC, and give an example in Figure 11.6. The AVC curve has a very similar shape to the AC curve and it gets closer and closer to the AC curve as Q increases. (Why? This is a good question to test your knowledge—see Thinking Problem 15 at the end of this chapter.)

We can summarize, therefore, all of the firm’s entry, exit, and shutdown decisions in Figure 11.6. If the price is so low that the firm can’t even cover its average variable cost, then the firm should shut down immediately and exit as soon as possible. If the price is high enough to cover the average variable cost but not all of the fixed costs (i.e., above AVC but below AC), then the firm should minimize its losses by producing the quantity such that P = MC (along the yellow curve) but exit as soon as possible. If the price is high enough to cover the firm’s average costs (at or above the AC curve), then the firm should remain in the industry or enter if it is not already in the industry and, of course, produce where P = MC.

FIGURE 11.6

By the way, the shutdown rule—shut down if you cannot cover your variable costs—can be applied in instances even when long-run exit is not at issue. Seasonal businesses, such as seaside hotels in the northeast of the United States, make their money during the busy season. What about in the winter when few people want to go to the beach? Do they stay open or close for a few months? It depends on whether these hotels can cover their variable costs in the slow season and contribute something to the paying of their fixed costs. This explains why it can sometimes make sense to run a hotel even when it is mostly empty.