CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 11.9

1. You’ve been hired as a management consultant to four different companies in competitive industries. They’re each trying to figure out if they should produce a little more output or a little bit less in order to maximize their profits. The firms all have typical marginal cost curves: They rise as the firm produces more.

Your staff did all the hard work for you of figuring out the price of each firm’s output and the marginal cost of producing one more unit of output at their current level of output. However, they forgot to collect data on how much each firm is actually producing at the moment. Fortunately, that doesn’t matter. In your final report, you need to decide which firms should produce more output, which should produce less, and which are producing just the right amount:

WaffleCo, maker of generic-brand frozen waffles. Price = $4 per box, marginal cost = $2 per box.

Rio Blanco, producer of copper. Price = $32 per ounce, marginal cost = $45 per ounce.

GoDaddy.com, domain name registry. Price = $5 per Web site, marginal cost = $2 per Web site.

Luke’s Lawn Service. Price: $80 per month, marginal cost = $120 per month.

Question 11.10

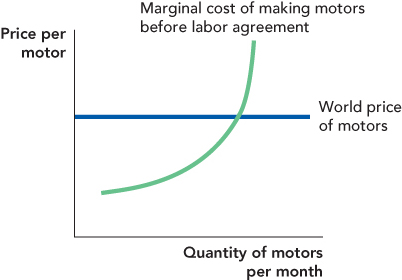

2. In the competitive electrical motor industry, the workers at Galt Inc. threaten to go on strike. To avoid the strike, Galt Inc. agrees to pay its workers more. At all other factories, the wage remains the same.

What does this do to the marginal cost curve at Galt Inc.? Does it rise, does it fall, or is there no change? Illustrate your answer in the figure.

What will happen to the number of motors produced by Galt Inc.? Indicate the “before” and “after” levels of output on the x-axis in the figure.

In this competitive market, what will the Galt Inc. labor agreement do to the price of motors?

Surely, more workers will want to work at Galt Inc. now that it pays higher wages. Will more workers actually work at Galt Inc. after the labor agreement is struck? Why or why not?

Question 11.11

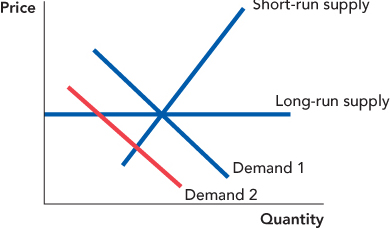

3. In Figure 11.8, you saw what happens in the long run when demand rises in a constant cost industry. Let’s see what happens when demand falls in such an industry: For instance, think about the market for gasoline or pizza in a small city after the city’s biggest textile mill shuts down. In the following figure, indicate the price and quantity of output at three points in time:

In the long run, before demand falls

In the short run, after demand falls

In the long run, after demand falls

Also, answer the following questions about the market’s response to this fall in demand.

When will the marginal cost of production be lowest: At stage I, II, or III?

When firms cut prices, they often do so in dramatic ways. During which stage will the local pizza shops offer “Buy one, get one free” offers? During which stage will the local gas station be more likely to offer “Free car wash with fill-up?”

When is P > AC? P < AC? P = AC?

Restating the previous question: When are profits positive? Negative? Zero?

Roughly speaking, will the long-run response mostly involve firms leaving the industry, or will it mostly involve individual firms shrinking? The Firm column of Figure 11.8 should help you with the answer.

Question 11.12

4. We mentioned that carpet manufacturing looks like a decreasing cost industry. In American homes, carpets are much less popular than they were in the 1960s and 1970s, when “wall-to-wall carpeting” was fashionable in homes. Suppose that carpeting became even less popular than it is today: What would this fall in demand probably do to the price of carpet in the long run?

Question 11.13

5. Replacement parts for classic cars are expensive, even though these parts aren’t any more complicated than parts for new cars.

What kind of industry is the market for old car parts: an increasing cost industry, a constant cost industry, or a decreasing cost industry? How can you tell?

If people began recycling old cars more in the United States—repairing them rather than sending them off to junkyards—would the cost of spare parts probably rise or probably fall in the long run? Why do you think so?

Question 11.14

6. Arguing about economics late one night in your dorm room, your friend says, “In a free market economy, if people are willing to pay a lot for something, then businesses will charge a lot for it.” One way to translate your friend’s words into a model is to think of a product with highly inelastic demand: items like life-saving drugs or basic food items. Let’s consider a market where costs are roughly constant: perhaps they rise a little or fall a little as the market grows, but not by much.

In the long run, is your friend right?

In the long run, what has the biggest effect on the price of a good that people really want: the location of the average cost curve or the location of the demand curve?

Question 11.15

7.

In the highly competitive TV manufacturing industry, a new innovation makes it possible to cut the average cost of a 50-inch plasma tv from $1,000 to $600. Most TV manufacturers quickly adopt this new innovation, earning massive short-run profits. In the long run, what will the price of a 50-inch plasma TV be?

In the highly competitive flash drive industry, a new innovation makes it possible to cut the average cost of an 8-gigabyte flash drive, small enough to fit in your pocket, from $5 to $4. In the long run, what will the price of a 8-gigabyte flash drive be?

Assume that the markets in parts a and b are both constant cost industries. If demand rises massively for these two goods, why won’t the price of these goods rise in the long run?

In constant cost industries, does demand have any effect on price in the long run?

When average cost falls in any competitive industry, regardless of cost structure, who gets 100% of the benefits of cost cutting in the long run: consumers or producers?

Question 11.16

8. On January 27, 2011, the price of Ford Motor Company stock hit an almost 10-year high at $18.79 per share. (Two years prior, in January 2009, Ford stock was trading for about a tenth of that price.)

Suppose that on January 27, 2011, you owned 10,000 shares of Ford stock (a small fraction of the almost 3.8 billion shares). Suppose you offered to sell your stock for $18.85 per share, just slightly above the market price. Would you have been successful?

What if, on January 27, 2011, you wanted to sell your 10,000 shares of Ford stock but you reduced your asking price to $18.75 per share? Would you have found a lot of willing buyers?

What do your answers for parts a and b tell you about the demand curve that you, as an individual seller of Ford stock, face?

Question 11.17

9. In November 2010 Netflix announced a new lower price for streaming video direct to home televisions. At the time, Netflix had no serious competitors—Netflix’s share of the digital download market was more than 60% (the second firm’s was only 8%). Just three months later, Amazon announced that it was entering the market for streaming video. How are these two announcements related?

Question 11.18

10. The chapter pointed out that whenever money is used to purchase capital, interest costs are incurred. Sometimes those costs are explicit—like when Alex borrowed the money from the bank—and sometimes those costs are implicit—like when Tyler had to forgo the interest he could have earned had he left his funds in a savings account. If an economist and accountant calculated Alex and Tyler’s costs, for whom would they have identical numbers and for whom would the numbers differ?

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 11.19

1. Suppose Sam sells apples, picked from his apple tree, in a competitive market. Assume all apples are equal in quality, but grow at different heights on the tree. Sam, being fearful of heights, demands greater compensation the higher he goes: So for him, the cost of grabbing an apple rises higher and higher, the higher he must climb, as shown in the Total Cost column in the following table. The market price of an apple is $0.50.

What is Sam’s marginal revenue for selling apples?

Which apples does Sam pick first? Those on the low branches or high branches? Why?

Does this suggest that the marginal cost of apples is increasing, decreasing, or staying the same as the quantity of apples picked increases? Why?

Page 216Complete the table.

Apples

Total Cost

Marginal Cost

Marginal Revenue

Change in Profit

1

$0.10

$0.10

$0.50

$0.40

2

$0.22

3

$0.50

4

$1.00

5

$1.73

6

$2.78

How many apples does Sam pick?

Question 11.20

2. How long is the “long run?” It will vary from industry to industry. How long would you estimate the long run is in the following industries?

The market for pretzels and soda sold from street carts in the Wall Street financial district in New York

The market for meals at newly trendy Korean porridge restaurants

The market for electrical engineers

After 2008, the market for movies that are suspiciously similar to Twilight

Question 11.21

3. In this chapter, we discussed the story of Dalton, Georgia, and its role as the carpet capital of the world. A similar story can be used to explain why some 60% of the motels in the United States are owned by people of Indian origin or why, as of 1995, 80% of doughnut shops in California were owned by Cambodian immigrants. Let’s look at the latter case. In the 1970s, Cambodian immigrant Ted Ngoy began working at a doughnut shop. He then opened his own store (and later stores).*

Ngoy was drawn to the doughnut industry because it required little English, startup capital, or special skills. Speaking the same language as your workers, however, helps a lot.

As other Cambodian refugees came to Los Angeles fleeing the tyrannical rule of the Khmer Rouge, which group—the refugees or existing residents—was Ngoy more likely to hire from? Why?

Did this make it more or less likely that other Cambodian refugees would open doughnut shops? Why?

As more refugees came in, did this encourage a virtuous cycle of Cambodian-owned doughnut shops? Why?

At this point in the story, what sort of cost industry (constant, increasing, or decreasing) would you consider doughnut shops owned by Cambodians to be? Why?

Why did this cycle not continue forever? What kind of cost structure are Californian doughnut shops probably in now?

Question 11.22

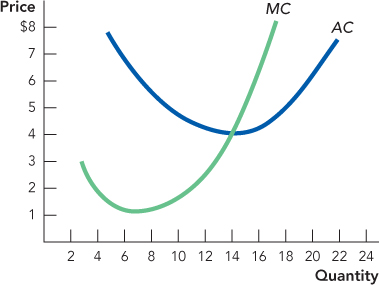

4. Ralph opened a small shop selling bags of trail mix. The price of the mix is $5, and the market for trail mix is very competitive. Ralph’s cost curves are shown in the figure below.

At what quantity will Ralph produce? Why?

When the price is $5, shade the area of profit or loss in the graph provided and calculate Ralph’s profit or loss (round up).

If all other sellers of trail mix have the same marginal and average costs as Ralph, should he expect more or fewer competitors in the future? In the long run, will the price of trail mix rise or fall? How do you know? What will the price of trail mix be in the long run?

Question 11.23

5. In the competitive children’s pajama industry, a new government safety regulation raises the average cost of children’s pajamas by $2 per pair.

If this is a constant cost industry, then in the long run, what exactly happens to the price of children’s pajamas?

If this is an increasing cost industry, will the long-run price of pajamas rise by more than $2 or less? (Hint: The long-run supply curve will be shaped just like an ordinary supply curve from the first few chapters. If you treat this like a $2 tax per pair, you’ll get the right answer.)

If this is an increasing cost industry, how much will this new safety regulation change the average pajama maker’s profits in the long run?

Given your answer to part c, why do businesses in competitive industries often oppose costly new regulations?

Question 11.24

6. In the ancient Western world, incense was one of the first commodities transported long distances. It grew only in the south of the Arabian Peninsula (modern-day Yemen, known then as Arabia Felix), which was transported by camel to Alexandria and the Mediterranean civilizations, notably the Roman Republic. As the republic expanded into a richer and larger empire, the demand for incense grew and planters in Arabia added a second and then a third annual crop (though this incense was not as high in quality). Cultivation also crossed to the Horn of Africa (modern-day Oman) even though such fields were farther away from Rome.2

How does the lower quality of the additional annual crops illustrate incense as an increasing cost industry? (Hint: Think in terms of an amount of good crop produced per unit of currency.)

How does the added distance of incense grown in the Horn of Africa illustrate incense as an increasing cost industry?

It’s more costly to grow incense in Eastern Africa than in Arabia Felix. Which region would you expect to see more incense grown in?

Question 11.25

7. You run a small firm. Two management consultants are offering you advice. The first says that your firm is losing money on every unit that you produce. To reduce your losses, the consultant recommends that you cut back production. The second consultant says that if your firm sells another unit, the price will more than cover your increase in costs. In order to reduce losses, the second consultant recommends that you should increase production.

As an economist, can you explain why both facts that the consultants rely on could be true?

Which consultant is offering the correct advice?

Question 11.26

8. Paulette, Camille, and Hortense each own wineries in France. They produce inexpensive, mass-market wines. Over the last few years, such wines sold for 7 euros per bottle; but with a global recession, the price has fallen to 5 euros per bottle. Given the information below, let’s find out which of these three winemakers (if any) should shut down temporarily until times get better. Remember: Whether or not they shut down, they still have to keep paying fixed costs for at least some time (that’s what makes them “fixed”).

To keep things simple, let’s assume that each winemaker has calculated the optimal quantity to produce if they decide to stay in business; your job is simply to figure out if she should produce that amount or just shut down.

|

Annual Income Statement When Price = 5 euros |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Winemaker |

Fixed Costs |

Variable Costs |

Recession Revenues |

Profits |

|

Paulette |

50,000 |

80,000 |

120,000 |

|

|

Camille |

100,000 |

40,000 |

70,000 |

|

|

Hortense |

200,000 |

250,000 |

200,000 |

|

First, calculate each winemaker’s profit.

Which of these women, if any, earned a profit?

Who should stay in business in the short run? Who should shut down?

Fill in the blank: Even if profit is negative, if revenues are _______ variable costs, then it’s best to stay open in the short run.

For which of these wineries, if any, is P > AC? You don’t need to calculate any new numbers to answer this.

Question 11.27

9. Suppose Carrie decides to lease a photocopier and open up a black-and-white photocopying service in her dorm room for use by faculty and students. Her total cost, as a function of the number of copies she produces per month, is given in the table:

|

Number of Photocopies Per Month |

Total Cost |

Fixed Cost |

Variable Cost |

Total Revenue |

Profit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0 |

$100 |

||||

|

1,000 |

$110 |

||||

|

2,000 |

$125 |

||||

|

3,000 |

$145 |

||||

|

4,000 |

$175 |

||||

|

5,000 |

$215 |

||||

|

6,000 |

$285 |

Fill in the missing numbers in the table, assuming that Carrie can charge 5 cents per black-and-white copy.

How many copies per month should Carrie sell?

If the lease rate on the copier were to increase by $50 per month, how would that impact Carrie’s profit-maximizing level of output? How would this $50 increase in the lease rate affect Carrie’s profit? What will she do when it is time to renew her lease?

Question 11.28

10. Let’s explore the relationship between marginal and average a little more. Suppose your grade in your economics class is composed of 10 quizzes of equal weight. You start off the semester well, then your grades start to slip a little, but then you get back into the swing of things, your grades pick up, and you finish off the semester with a bang. Your 10 quiz grades, in order, are: 82, 74, 68, 72, 77, 83, 86, 88, 90, and 100. Graph your marginal grades, along with your average grade, after each quiz. What do you notice about the relationship between marginal and averages? Your grades start improving with your fourth quiz grade; does your average also start increasing with your fourth quiz grade? Why or why not?

Question 11.29

11. Given the cost function in the following table for Simon, a housepainter in a competitive local market, answer the questions that follow. (You may want to calculate average cost.)

|

Number of Rooms Painted per Week |

Total Cost |

|---|---|

|

0 |

$100 |

|

1 |

$120 |

|

2 |

$125 |

|

3 |

$145 |

|

4 |

$200 |

|

5 |

$300 |

|

6 |

$460 |

What is the minimum price per room at which Simon would be earning positive economic profit? At prices below this price, what will Simon’s long run plan be?

Question 11.30

12. Sandy owns a firm with annual revenues of $1,000,000. Wages, rent, and other costs are $900,000.

Calculate Sandy’s accounting profit.

Suppose that instead of being an entrepreneur, Sandy could get a job with one of the following annual salaries (i) $50,000; (ii) $100,000; or (iii) $250,000. Assume that a job would be as satisfying to Sandy as being an entrepreneur. Calculate Sandy’s economic profit under each of these scenarios.

Question 11.31

13. You and your roommate are up one night studying microeconomics, and your roommate looks puzzled. You ask what is wrong, and you get this response: “The book says that in the short run fixed costs are an expense but not a cost—but that doesn’t make any sense. How can something be an expense but not a cost?” How do you respond?

Question 11.32

14. Use the variable cost information in the following table to calculate average variable cost and average cost (assume fixed cost is $350), and then use this data to answer the questions that follow. One of them might not have an answer.

|

Q |

FC |

VC |

AVC |

AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

10 |

$350 |

$100 |

||

|

20 |

$350 |

$180 |

||

|

30 |

$350 |

$240 |

||

|

40 |

$350 |

$300 |

||

|

50 |

$350 |

$450 |

||

|

60 |

$350 |

$630 |

||

|

70 |

$350 |

$840 |

Give an example of a price at which this firm would want to produce and sell output in both the short run and the long run.

Give an example of a price at which this firm would want to produce and sell output in neither the short run nor the long run.

Give an example of a price at which this firm would want to produce and sell output in the long run but not in the short run.

Give an example of a price at which this firm would want to produce and sell output in the short run but not in the long run.

Question 11.33

15. Look carefully at Figure 11.6. What is represented by the space in between the average cost (AC) and average variable cost (AVC) curves? Why do they get closer together as quantity increases? Will they ever meet?

CHALLENGES

Question 11.34

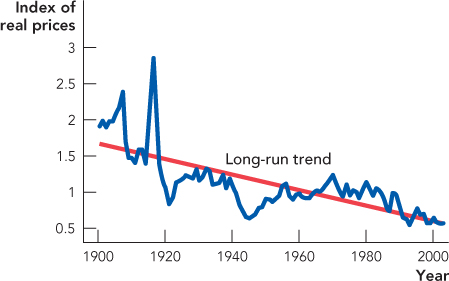

1. The demand for most metals tends to increase over time. Moreover, as we discussed in this chapter and also in Chapter 5, these types of natural resource industries tend to be increasing cost industries. And yet the price of metals compared with other goods has tended to fall slowly over time (albeit with many spikes in between). The following figure, for example, shows an index of prices for aluminum, copper, lead, silver, tin, and zinc from 1900 to 2003 (adjusted for inflation). The trend is downward. Why do you think this is the case?

Question 11.35

2. Frequent moviegoers often note that movies are rarely based on original ideas. Most of them are based on a television series, a video game, or, most commonly, a book. Why? To help you answer this question, start with the following.

Does a movie or a book have a higher fixed cost of production?

In 2005, American studios released 563 movies and American publishers produced 176,000 new titles. How does your answer in part a explain such a wide difference? Which is riskier: publishing a book or producing a movie?

How does the difference in fixed costs and risk of failure explain why so many movies are based on successful books? As a result, where do you expect to see more innovative plots, dialogues, and characters: in novels or movies?

Question 11.36

In the nineteenth century, economist Alfred Marshall wrote about decreasing cost industries, writing in his Principles of Economics (available free online) that “when an industry has thus chosen a locality for itself …. [t]he mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are as it were in the air.” In Chapter 10, we had a concept for benefits that are not internal to a firm but are “as it were in the air.” What specific concept from Chapter 10 is at work in a business cluster?

In the twenty-first century, economist Michael Porter of the Harvard Business School writes about decreasing cost industries, as well: He calls them “business clusters.” Porter’s work has been very influential among city and town governments that argue carefully targeted tax breaks and subsidies can attract investment and create a business cluster in their town, which will subsequently reap the benefits of decreasing costs. Is this argument correct? Be careful, it’s tricky!

Page 220

Question 11.37

4. In Kolkata, India, it is very common to see beggars on the streets. Imagine that the visitors and residents of Kolkata become more generous in their donations; what will be the effect on the standard of living of beggars in Kolkata? Answer this question using supply and demand, making assumptions as necessary.

Question 11.38

5. Just to make sure you’ve gotten enough practice using the different formulas in this chapter, let’s try a challenging exercise with them. Very little information is given in the following table, but surprisingly, there’s enough information for you to fill in all of the missing values—if you remember all of the relationships and can think of creative ways to use them.

|

Quantity |

Total Cost |

Fixed Cost |

Variable Cost |

Average Cost |

Marginal Cost |

Total Revenue |

Profit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0 |

— |

— |

–80 |

||||

|

10 |

$4 |

||||||

|

20 |

$200 |

||||||

|

30 |

$240 |

$450 |

|||||

|

40 |

|||||||

|

50 |

$13.60 |

$20 |

WORK IT OUT

Suppose Margie decides to lease a photocopier and open up a black-and-white photocopying service in her dorm room for use by faculty and students. Her total cost, as a function of the number of copies she produces per month, is given in the table:

|

Number of Photocopies Per Month |

Total Cost |

Fixed Cost |

Variable Cost |

Total Revenue |

Profit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0 |

$100 |

||||

|

1,000 |

$110 |

||||

|

2,000 |

$125 |

||||

|

3,000 |

$145 |

||||

|

4,000 |

$175 |

||||

|

5,000 |

$215 |

||||

|

6,000 |

$285 |

Fill in the missing numbers in the table, assuming that Margie can charge 6 cents per black-and-white copy.

How many copies per month should Margie sell?

If the lease rate on the copier were to increase by $50 per month, how would that impact Margie’s profit-maximizing level of output? How would this $50 increase in the lease rate affect Margie’s profit? What will she do when it is time to renew her lease?