The Costs of Monopoly: Corruption and Inefficiency

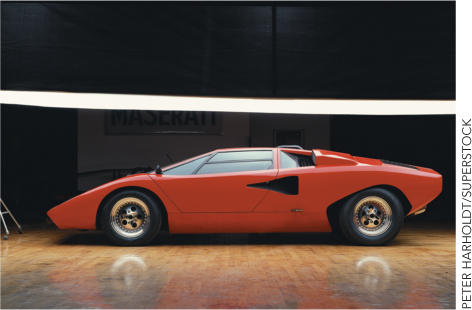

Sadly, around the world today, many monopolies are government-created and born of corruption. Indonesian President Suharto (in office from 1967 to 1998), for example, gave the lucrative clove monopoly to his playboy son, Tommy Suharto. Cloves may sound inconsequential, but they are a key ingredient in Indonesian cigarettes, and the monopoly funneled hundreds of millions of dollars to Tommy. A lot of rich playboys buy Lamborghinis—Tommy bought the entire company.

Monopolies are especially harmful when the goods that are monopolized are used to produce other goods. In Algeria, for example, a dozen or so army generals each control a key good. Indeed, the public ironically refers to each general by the major commodity that they monopolize—General Steel, General Wheat, General Tire, and so forth.

Steel is an input into automobiles, so when General Steel tries to take advantage of his market power by raising the price of steel, this increases costs for General Auto. General Auto responds by raising the price of automobiles even more than he would if steel were competitively produced. Similarly, General Steel raises the price of steel even more than he would if automobiles were competitively produced. Throw in a General Tire, a General Computer, and, let’s say, a General Electric and we have a recipe for economic disaster. Each general tries to grab a larger share of the pie, but the combined result is that the pie gets much, much smaller.

Compare a competitive market economy with a monopolized economy: Competitive producers of steel work to reduce prices so they can sell more. Reduced prices of steel result in reduced prices of automobiles. Cost savings in one sector are spread throughout the economy, resulting in economic growth. In a monopolized economy, in contrast, the entire process is thrown into reverse. Each firm wants to raise its prices, and the resulting cost increases are spread throughout the economy, resulting in poverty and stagnation.

One of the great lessons of economics is to show that good institutions channel self-interest toward social prosperity, whereas poor institutions channel self-interest toward social destruction. Business leaders in the United States are no less self-interested than generals in Algeria. So why are the former a mostly positive force, while the latter are a mostly negative force? It’s because competitive markets channel the self-interest of business leaders toward social prosperity, whereas the political structure of Algeria channels self-interest toward social destruction.