Price Discrimination Is Common

Once you know the signs, price discrimination is easy to see. Movie theaters, for example, often charge less for seniors than for younger adults. Is this because theater owners have a special respect for the elderly? Probably not. More likely it’s that theater owners realize that young people have a more inelastic demand for movies than seniors. Thus, theater owners charge a high price to young people and a low price to seniors. It would probably be even more profitable if theater owners could charge people who are on a date more than married people (no one likes to look cheap on a date). But it’s easy for theater owners to judge age and not so easy for them to figure out who is on a date and who is married.

Students don’t always pay higher prices, however. Stata is a well-known statistical software package. It costs a business $1,295 to buy Stata, but registered students pay only $145. Thus, it’s not about age—the young sometimes pay more and sometimes pay less—it’s about how age correlates with what businesses really care about, which is how much the customer is willing to pay.

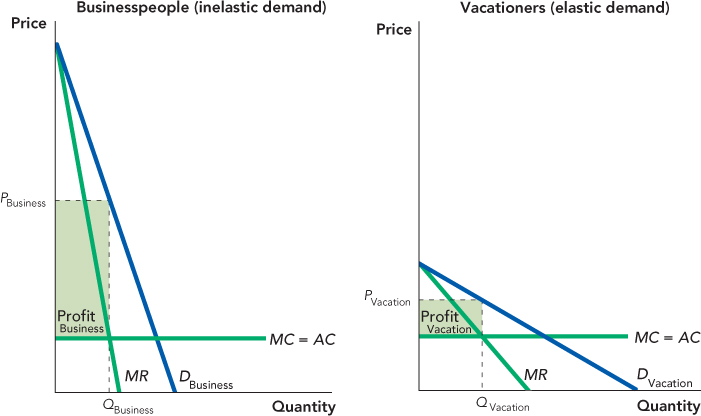

Here’s another example. Airlines know that businesspeople are typically less sensitive to the price of an airline ticket than are vacationers (i.e., businesspeople have more inelastic demand curves). An airline would like, therefore, to set a high price for businesspeople and a low price for vacationers, as illustrated in Figure 14.2.

FIGURE 14.2

But airlines can’t very well say to their customers, “Are you flying on business? Okay, the price is $600. Going on a vacation? The price is $200.” So how can airlines segment the market?

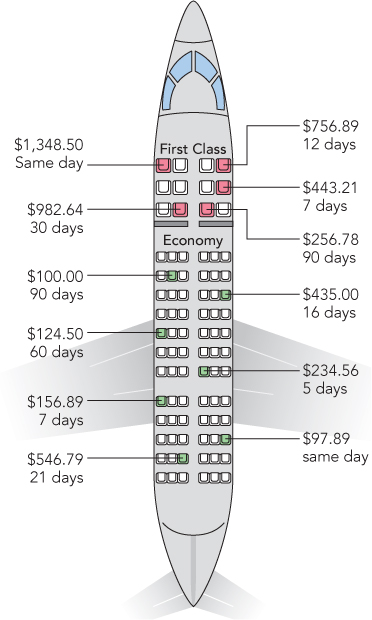

Airlines set different prices according to characteristics that are correlated with the willingness to pay. Vacationers, for example, can easily plan their trips weeks or months in advance. Businesspeople, however, may discover that they need to fly tomorrow. Thus, if a customer wants to fly to Tampa, Florida, in two weeks’ time he or she is probably a vacationer and the airline will charge that person a low price, but if the customer wants to fly tomorrow, the price will be higher. On the day these words were written, U.S. Airways was charging $113 to fly from Washington, D.C., to Tampa with two weeks’ notice but more than three times as much, $395, to fly tomorrow. Except for the dates the flights were identical. Figure 14.3 illustrates how one airline charged many different prices for the same flight.

FIGURE 14.3

Similarly, publishers know that hard-core fans are willing to pay a high price for the latest Harry Potter book, while others will buy only if the price is low. Publishers would like to charge the hard-core fans a high price and the less devoted a low price. How can they do this? One way is to start with a high price and then lower it once the hard-core fans have bought their fill. Thus, when Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince hit the shelves, it retailed at $34.99 in hardback, but when the paperback was released about a year later, it sold for just $9.99. Does it cost more to produce a hardback? Yes, but not much more, maybe a dollar or two. The hard-core fans pay a higher price not because costs are higher, but because the publisher knows that they are willing to pay a higher price.

A more subtle form of price discrimination occurs when firms offer different versions of a product for the purpose of segmenting customers into different markets. IBM, for example, offered one of its laser printers in two models: the regular version and the Series E (E for economy). The regular version printed at 10 pages per minute, the Series E printed at 5 pages per minute. The regular version was much more expensive than the Series E. What’s surprising is that the Series E cost more to produce. In fact, the only difference between the regular and the Series E was that the Series E printer contained an extra chip that slowed the printer down! IBM wasn’t charging more for the regular printer because that printer cost more to produce; it was charging more because it knew that the demand for speed was correlated with willingness to pay.

Universities and Perfect Price Discrimination

Universities are one of the biggest practitioners of price discrimination, although they hide this practice under the blanket of “student aid.” Student aid is a way of charging different students different prices for the same good. Consider Williams College, a small, prestigious liberal arts college. In 2001, some students at Williams paid the sticker price of $32,470, while others paid just $1,683 for exactly the same education. Why the big difference in price?

Part of the story is that Williams College was doing good by offering financial aid to students from poorer families. But Williams College was also doing well. To see why, notice that Williams College is a lot like an airline. If U.S. Airways is going to fly an airplane from New York to Los Angeles anyway, then U.S. Airways can increase its profits by filling extra seats so long as its customers are willing to pay the marginal costs of flying (say, the extra fuel costs). Of course, if a customer is willing to pay $800 to fly to LA., then U.S. Airways wants to charge that customer $800 and not less. But if the marginal cost of flying is $100, then U.S. Airways can increase its profits by filling an empty seat so long as the customer is willing to pay at least $101.

Williams College is a lot like an airline because if Ancient Greek History 101 is going to be taught anyway, then Williams can increase its profits by filling extra seats so long as its students are willing to pay the marginal costs of teaching. Of course, if a student is willing to pay $32,470 for a year of education at Williams, then Williams wants to charge that student $32,470 and not less. But if the marginal costs of teaching are $1,682 a year, then Williams can increase its profits by filling an empty seat so long as the student is willing to pay at least $1,683.

About half the students at Williams paid the full sticker price of $32,470, but half did not. Table 14.1 shows the average price paid by students in five different income classes, low to high, after taking into account “financial aid.”

TABLE 14.1 Price Discrimination at Williams College, 2001–2002

|

Income Quintile |

Family Income Range |

Net Price After Financial Aid |

|---|---|---|

|

Low |

$0–$23,593 |

$1,683 |

|

Lower Middle |

$23,594–$40,931 |

$5,186 |

|

Middle |

$40,932–$61,397 |

$7,199 |

|

Upper Middle |

$61,398–$91,043 |

$13,764 |

|

High |

$91,044+ |

$22,013 |

|

Note: Students who did not apply for financial aid paid $32,470. Source: Hill, Catharine B., and Gordon C. Winston. 2001. Access: Net Prices, Affordability, and Equity at a Highly Selective College. Williams College, DP-62. |

||

The difference in price is extreme. Even the airlines, masters of price discrimination, can rarely charge some customers 20 times what they charge other customers. Williams has a big advantage over the airlines, however. Williams has an extraordinary amount of information about its customers.

Under perfect price discrimination (PPD), each customer is charged his or her maximum willingness to pay.

To receive financial aid, Williams demands that students and their parents submit their tax returns to Williams. Williams, therefore, has very detailed information about the income of its customers, and it uses that information to set many different prices. Table 14.1 shows average prices within each income class, but, in fact, Williams divided prices even more finely, setting a different price, for example, to a student with family income of $30,000 than one with family income of $35,000. In theory, Williams could offer a different price to each one of it students, charging each student his or her maximum willingness to pay. This is what economists call perfect price discrimination.

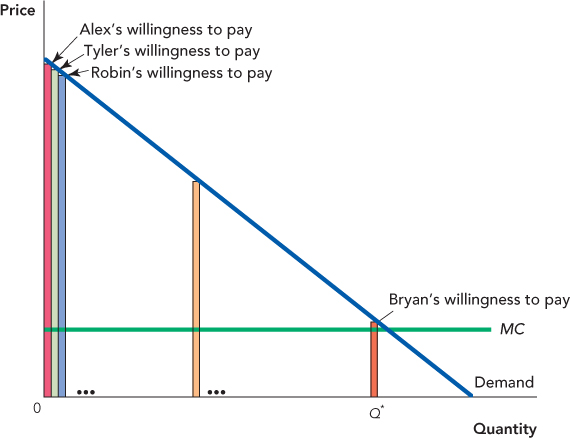

Figure 14.4 shows how perfect price discrimination works in a market like education, where each customer buys one unit of the good. Alex values education the highest, Tyler the second highest, Robin the third highest, all the way down to Bryan who thinks that education has very little value. A firm that has a lot of information about Alex, Tyler, Robin, and Bryan can set four different prices, charging each of them their maximum willingness to pay (or, if you like, a penny less than their maximum willingness to pay). Thus, Alex is charged the most and Bryan the least.

FIGURE 14.4

Since a perfectly price-discriminating (PPD) monopolist charges each consumer his or her maximum willingness to pay, consumers end up with zero consumer surplus. All of the gains from trade go to the monopolist. This is bad for consumers but does have a beneficial side effect: Since the PPD monopolist gets all the gains from trade, the PPD monopolist has an incentive to maximize the gains from trade, and maximizing the gains from trade means no deadweight loss.

In Chapter 13, we showed that a single-price monopoly creates a deadweight loss, but this is not true for a perfectly price-discriminating monopoly. In Figure 14.4, notice that whenever a consumer’s willingness to pay is higher than marginal cost, then that consumer is sold a unit of the good—but this means that the PPD monopoly produces the efficient quantity! In fact, the perfectly price-discriminating monopolist produces until P = MC (i.e., Q* units), exactly as does a competitive firm!

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 14.4

Is the early bird special (eating dinner at a restaurant before 6:00 pm or 6:30 pm) a form of price discrimination? If so, what are the market segments? Can you think of another explanation for this type of pricing?

Is the early bird special (eating dinner at a restaurant before 6:00 pm or 6:30 pm) a form of price discrimination? If so, what are the market segments? Can you think of another explanation for this type of pricing?

Question 14.5

Why is it much more expensive to see a movie in a theater than to wait a few months and see it at home on DVD? Can you give an explanation based on price discrimination?

Why is it much more expensive to see a movie in a theater than to wait a few months and see it at home on DVD? Can you give an explanation based on price discrimination?

Another way of seeing why the perfectly price-discriminating monopolist produces the efficient quantity is to remember that all firms want to produce until MR = MC. For a competitive firm, MR = P, so the competitive firm produces until P = MC. For a single single-price monopolist, MR < P, so the single-price monopolist produces less than the competitive firm. But what is MR for a PPD monopolist? It’s P and thus the PPD monopolist also sets P = MC. Can you explain why as a PPD monopolist moves down the demand curve selling to additional customers, its MR is always equal to price?

Detailed information about its customers helps Williams College set each student’s price close to that student’s maximum willingness to pay, thus maximizing Williams’s revenue. Ever wonder why many retailers ask for your zip code when they ring up your purchase? More information means more profit. Ever wonder why used car salespeople are so friendly? Sure, friendliness helps to sell cars, but what you think of as friendly talk is really a clever strategy to learn as much about you as possible so the salesperson can price accordingly. When buying a new car, one of the authors of this book always tells the salesperson he is a student. Alas, the ruse is becoming less believable as the years wear on.