The “Best” Product May Not Always Win

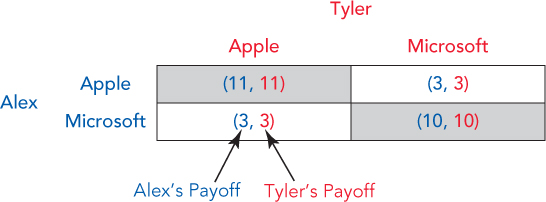

In markets with network goods, it’s possible for the market to “lock in” to the “wrong” product or network. We can illustrate using a coordination game as shown in Figure 16.1, similar in structure to the prisoner’s dilemma we showed in the previous chapter. Alex and Tyler are choosing whether to use software from Apple or Microsoft to write their textbook. Alex’s choices or strategies are the rows, Tyler’s are the columns. What Alex and Tyler most want to avoid is making different choices. If Alex chooses Microsoft and Tyler chooses Apple, it will be difficult for them to work together so their payoffs will be low, just (3,3). And the same thing is true if Alex chooses Apple and Tyler chooses Microsoft. Alex and Tyler receive the highest payoffs if both are using the same software. So, if Alex chooses Apple, it will make sense for Tyler to choose Apple, and vice versa. In other words, if Alex and Tyler both choose Apple, then neither will have an incentive to change his strategy.

FIGURE 16.1

A Nash equilibrium is a situation in which no player has an incentive to change his or her strategy unilaterally.

More formally, economists say a situation is an equilibrium if no player in the game has an incentive to change his or her strategy unilaterally. This is also called a Nash equilibrium after John Nash, the mathematician. The outcome (Apple, Apple) is an equilibrium because neither Alex nor Tyler has an incentive to change his strategy unilaterally, that is, given that Tyler chooses Apple, Alex wants to choose Apple and vice versa.

A coordination game is one in which the players are better off if they choose the same strategies than if they choose different strategies and there is more than one strategy on which to potentially coordinate.

But notice that (Apple, Apple) is not the only equilibrium in this coordination game. If Alex chooses Microsoft, then Tyler will also want to choose Microsoft, and vice versa. Thus, (Microsoft, Microsoft) is also an equilibrium strategy. The payoffs to the (Microsoft, Microsoft) equilibrium are slightly lower than the payoffs to the (Apple, Apple) equilibrium. Nevertheless, (Microsoft, Microsoft) is still an equilibrium because if Alex and Tyler do choose Microsoft, neither will have an incentive to switch. So which equilibrium, (Apple, Apple) or (Microsoft, Microsoft), will Alex and Tyler end up at?

If Alex and Tyler really are the only players in this game, they could probably talk to each other and coordinate on the best equilibrium, which is (Apple, Apple). But in reality the coordination game is between Alex, Tyler, and many other people. Coordinating on the best equilibrium is not so easy when many people are involved and when they do not all agree about whether Apple really is better than Microsoft. So what will determine the final equilibrium? The classic answer is “accidents of history.”

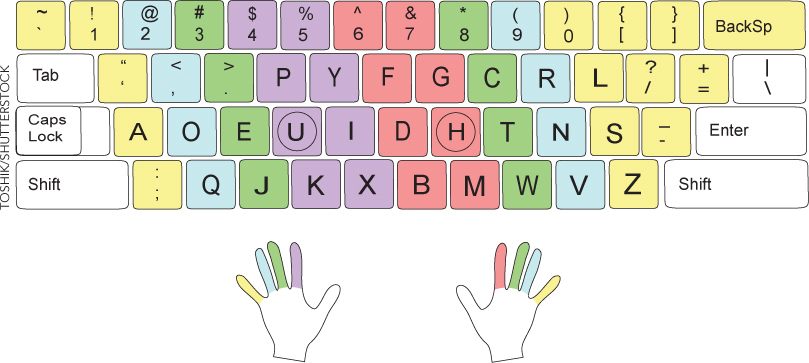

It’s an accident of history that computer keyboards are laid out according to the QWERTY design (so named for the keys on the top left side). But is QWERTY the best possible layout for keyboards? According to some studies, a different layout of the keys called the Dvorak design allows for faster and easier typing. So why is the QWERTY design dominant? QWERTY came first, and once people learned to type on a QWERTY keyboard, typewriter manufacturers had an incentive to sell QWERTY typewriters. And, of course, once most manufacturers were selling QWERTY typewriters, it made sense to learn how to type on the QWERTY keyboard. Thus, the QWERTY design became “locked in.” If you’re wondering, QWERTY is the only way that your authors know how to type.

The QWERTY story needs to be taken with a grain of salt, however. The first study showing that the Dvorak layout was better than QWERTY was a 1944 study by the U.S. Navy. But who authored the 1944 study? None other than Lieutenant-Commander August Dvorak. Any guesses as to who created the Dvorak keyboard? Later studies have failed to show big advantages to either keyboard. Thus, it makes sense that few people bother to learn Dvorak even though it’s now easy to reprogram a computer keyboard according to any design.*

When networks are important, product design isn’t just about the stand-alone product, it is also about making sure the product fits into the rest of the industry and about making things easy for as many users as possible. Microsoft’s competitors like Apple have at times arguably had the superior products in stand-alone terms, but Apple has not been better at ensuring widespread compatibility and an easy-to-use industry standard. Designing products that everyone can use will often mean a certain amount of simplification and a certain number of shortcuts. It is precisely the experts who will be most unhappy with a mass-compatible product. That is one reason why some people say “Microsoft is evil,” but in part this charge is the result of wishful thinking that everyone could be an advanced computer user.