Labor Market Issues

Now that we know the basic principles underlying the demand and supply of labor, let’s turn to some specific questions and issues that our principles can help us to understand.

Why Do Janitors in the United States Earn More than Janitors in India Even When They Do the Same Job?

The short answer for why janitors in the United States earn more for the same type of work as janitors in India is that the janitors in the United States are working for very productive firms, such as McDonald’s. The productivity of American firms and offices in general raises the marginal product of labor and thus the wages of American janitors. Indian janitors might work as hard or harder than American janitors but they are less productive and have lower wages because they work in a less productive economy.

Let’s look at the differences between the typical American and Indian office building a little more closely. The American office building has more and better equipment, more fax machines, more computers, and more copiers. Overall, there is more capital invested in the American workplace, and American office workers, on average, are better educated than office workers in India. That makes the American office building more productive. The American office building also has a better marketing department, longer global reach for its sales force, and greater investment in building up the brand name of the product. Most important, the American office is producing a more valuable product.

Since it’s more valuable to keep a productive workplace clean than to keep a less productive workplace clean, the wages of American janitors are higher than those in India.

To put it in a single sentence, the American janitor gets the benefit of productivity in many other sectors of the American economy. A typical janitor in India might earn less than $1,000 per year. That same worker, if he wins the green card lottery and comes to the United States, might instead earn over $20,000 in a similar job or even up to $30,000, depending on location and hours. It’s not that he has suddenly learned new cleaning techniques but rather that he is working in a more productive economy.

There is no doubt that you are a very productive person—perhaps you know how to use a computer, have some artistic talents, and write well. Now look around the world—how much would these skills earn you in another country? Your skills are yours alone, but your wage is determined not by your skills alone but by the productivity of the entire economy.

Of course, wages are about supply as well as demand. India has more workers than the United States, but what’s more important than India’s total population is that India has a great many low-skilled workers who eagerly compete for the job of janitor. A much greater proportion of Indians than Americans, for example, would consider a cleaning job in a modern office building to be a very attractive job. Since many Indians compete for the job of janitor, the wages of janitors are pushed down.

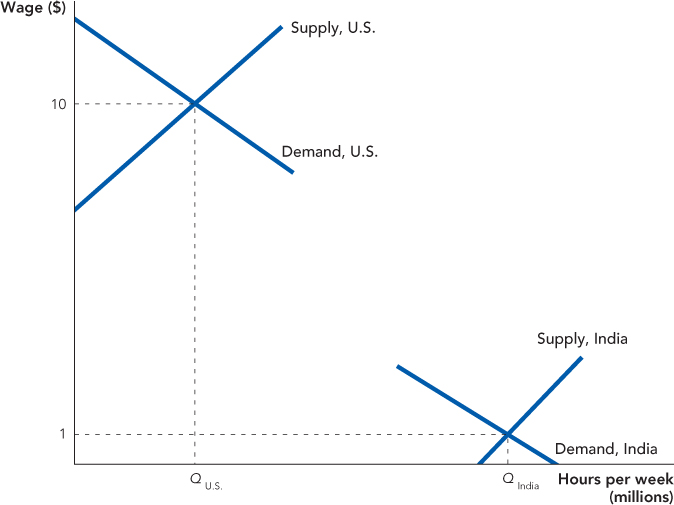

Figure 18.4 shows the two reasons why the wages of janitors are lower in India than in the United States. First, the demand for janitors is higher in the United States because U.S. firms are more productive than firms in India overall. Second, the supply of low-skilled labor in India is higher than in the United States.

FIGURE 18.4

Human Capital

Americans are fortunate to work in a productive economy. But high wages are not just the result of fortunes of birth. Wages within America differ greatly from worker to worker so let’s look at some of the reasons why.

Human capital is tools of the mind, the stuff in people’s heads that makes them productive.

Some workers have higher wages than others because they have more human capital. Physical capital is tools like computers, bulldozers, and 3D printers. Human capital is tools of the mind, the stuff in people’s heads that makes them productive. Human capital is not something we are born with—it is produced by investing time and other resources in education, training, and experience.

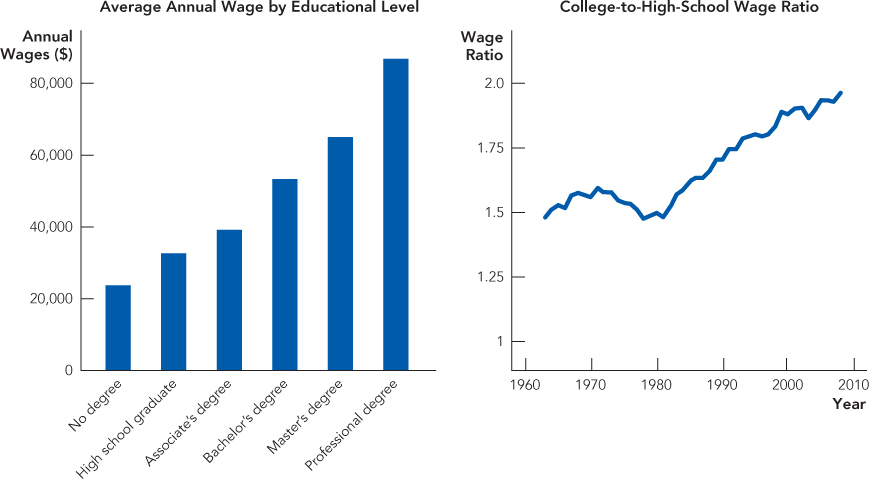

Of course, investing in human capital usually costs money; it costs not just what a doctor spends on medical school tuition but what he or she could have earned during those eight years in medical school, namely opportunity cost. But, in general, investments in human capital bring a good return in the United States. In recent years, college graduates have made almost twice as much as high school graduates.

Panel a of Figure 18.5 shows annual wages by education level. Clearly more education, on average, brings a higher wage.

FIGURE 18.5

Source, Panel a: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source, Panel b: Autor, D. 2010. The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress and The Hamilton Project.

Panel b shows that the return to a college education has been rising over time. College pays off more now than ever before. The line is the ratio of the wages of college graduates to that of high school graduates, or the “college wage premium.” From the 1960s to the 1980s, wages for people with a college degree were approximately 1.5 times higher than the wages of a high school graduate. Today, however, wages for people with a college degree are almost double the wages of a high school graduate, in part because wages for those with college degrees have been going up and also in part because wages for those with just a high school degree have been going down.

Why is the return to human capital rising so strongly? Some economists believe that the ability to work with computers has made an education more valuable than in times past. Another hypothesis is that bottlenecks in the U.S. system of grade-school education are lowering student quality and thus limiting the flow of new people into the ranks of the college-educated, thus raising the return to a college education. It’s also the case that technology and greater competition from developing countries have limited or reduced wage growth for Americans with low skills. In any case, it’s more important to finish college than it used to be, at least in terms of the wages you can expect to earn.

We should also mention that the return to education is not just about human capital. Have you ever wondered why an art history major earns a higher income than a high school graduate even though neither works in the field of art history? An employer may want to hire someone with a college degree not because of anything he or she learned at college but because the very fact that this individual earned a degree signals to the employer something good about the job candidate, namely that he or she has enough intelligence, competence, and conscientiousness to earn a college degree (we discuss signaling at greater length in Chapter 24). For the same reasons, if you have ever completed an Ironman triathlon, you might want to subtly indicate that on your résumé (say, under “Interests”) even if the job you are applying for requires no athletic ability. Competing in an Ironman triathlon doesn’t increase your productivity at managing an advertising department, but it does indicate that you are the type of person who doesn’t give up easily and that is a characteristic employers frequently seek.

Compensating Differentials

The supply of labor depends on the real wage, but the real wage of a job includes not just the monetary pay but also how much fun the job is. Some people work for nice bosses; others work for tyrants. Some jobs are dangerous; others are very safe. Some jobs are interesting; others are a bore.

Right now being a fisherman is the most dangerous job in the United States, more dangerous than being a police officer or a firefighter. There are a lot of accidents out on the water. Most of all, a lot of people just slip and fall overboard. Being a truck driver is dangerous, too, mostly because of road accidents. That’s why those professions earn relatively high wages, especially given that they do not demand a college degree.1

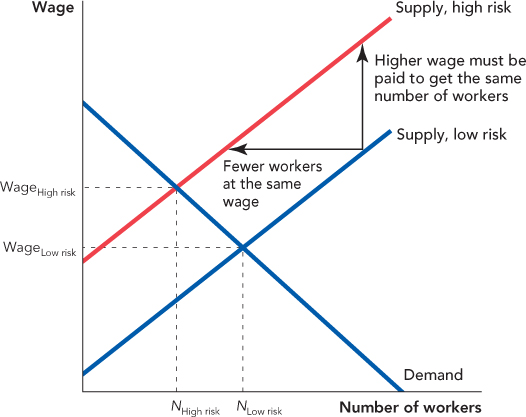

It’s simple supply and demand. The danger of a dangerous job reduces the supply of labor, pushing the supply curve for labor to the left and up, as shown in Figure 18.6.

FIGURE 18.6

A compensating differential is a difference in wages that offsets differences in working conditions.

The resulting wage is higher than it otherwise would be, and that is what economists call a compensating differential. It is called a compensating differential because a difference in wages compensates for the difference in working conditions.

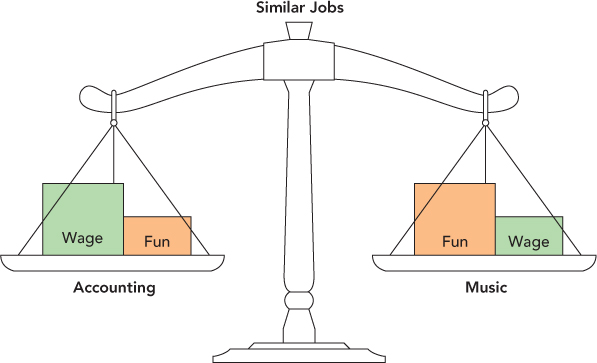

There’s a lesson here. People talk all the time about wanting interesting, fun, and rewarding jobs but beware: being an accountant might be boring, but all else being equal, that’s a sign of higher wages. Being a musician is fun but most musicians don’t make a lot of money. The higher wage of accountants compensates for the lack of fun or, equivalently, the greater fun of being an artist compensates for the lack of money.

To see this in more detail, consider the following principle: Similar jobs must have similar compensation packages. Imagine that being an accountant or a musician requires similar amounts of skill, education, training, and so forth. Now what would happen if musicians were paid higher wages than accountants? Higher wages and more fun can’t be beat so the supply of musicians will increase and the supply of accountants will decrease. But the increased supply of musicians will drive down the wages of musicians and the decreased supply of accountants will drive up the wages of accountants. In fact, musician wages will fall and accountant wages will rise until a typical young person deciding on a career will be more or less indifferent: Higher wages and less fun equal lower wages and more fun. Figure 18.7 illustrates the main idea.

FIGURE 18.7

Every job has a different combination of wages, benefits, fun, risk, and other conditions. Some workers will choose jobs with less risk but lower wages, while others will prefer jobs with more risk but higher wages. In fact, workers who choose the less risky jobs are “buying” safety with a reduction in their wages. Now consider who is more likely to buy safety, a rich worker or a poor worker?

The rich buy more safety for the same reason they buy more BMWs—buying safety is one of the things that money is good for! We’ve already noted that being a fisherman is a dangerous job. It should come as no surprise that many of these fishermen are recent immigrants to the United States. But it’s not the immigrants from wealthy Sweden who take the fishing jobs. Instead, it’s poor immigrants from Honduras who concentrate in the fishing trade. These poorer immigrants need the money the most and are less willing to buy safety by taking jobs with lower wages.

The same reasoning explains why jobs in the United States are much safer than similar jobs in poorer countries. Workers in the United States use their wealth to buy more smoke detectors, fire extinguishers, and airbags on their cars and they also “buy” more job safety. Thus, one of the most important reasons why job safety increases over time is economic growth.

In other words, workers become less willing to accept risk as economic growth makes them wealthier. You might take a dangerous job if you need the money to feed your family, but not if you need the money to feed your family at The French Laundry, one of the best and most expensive restaurants in the United States.

Government regulation has improved the quality of American jobs, as well (see below), but increasing wealth and the profit incentive are the main drivers behind this process. Are you surprised that the pursuit of profit leads to greater job safety? Remember that firms must pay workers to take on higher risks, the compensating differentials we talked about earlier. But the process works the other way just as well—when firms make jobs safer, they can pay lower wages, thus increasing their profits.

Take a job like coal mining. An American coal miner will earn between $50,000 to $80,000 annually—let’s say for purposes of argument, $70,000.2 If that sounds like a pretty good wage to you, it is because coal mining is not especially fun. But how much would wages have to be if coal mining in the United States were as dangerous as in China, where the mortality rate per ton of coal is 100 times higher? Coal miners might demand $100,000 to take on the extra risk. That’s an extra $30,000 per coal miner per year that firms would have to pay because of riskier working conditions. If the mining company can make the mines safer for less than that, obviously their incentive is to invest in safety.

Economists have estimated how much more firms must pay American workers to take on risk and the numbers are very large, by one estimate $245 billion in recent years. In comparison, OSHA (the Occupational Safety and Health Administration), which oversees workplace safety, levies fines every year of about $150 million. These numbers imply that fear of government fines is not that big a cost, compared with having to pay higher wages for riskier jobs. In other words, market competition—employers luring laborers by offering better packages of wages and working conditions—is the major factor in making jobs safer.

So, as workers become wealthier and less willing to take on risk, firms have greater incentives to increase job safety—which explains why jobs are safer today than they were in the past and why jobs are safer in wealthier countries than in poorer countries.

The pursuit of profit, however, doesn’t always lead to greater safety, which is why government regulation also has a role to play. Compensating differentials give firms an incentive to increase safety only if workers know that a job is risky. If workers don’t know about or underestimate risk, they won’t demand higher wages. A government agency like OSHA can help to ensure that firms do not hide job risks. Even more important, in the United States, firms are required to buy workers’ compensation insurance—which pays workers for on-the-job injuries. Crucially, the premiums that firms must pay to buy this insurance are experienced-based, which means that the more injuries a firm has, the more it must pay for insurance. Thus, workers’ compensation programs give firms an incentive to reduce risk so they can save money on insurance. Since the insurance premiums a firm must pay are based on actual injuries, this incentive works even when workers do not know or underestimate risk.

Do Unions Raise Wages?

It is commonly suggested that unions are a fundamental reason why wages are so high in some countries and so low in other countries. Yet the evidence does not bear out this view. The more unionized countries do not obviously have higher levels of wages. For instance, the United States and Switzerland have much lower levels of unionization (11% and 18%, respectively, in recent years) than does most of Western Europe, where unionization rates can run between 30% and 80%. Yet the United States and Switzerland have equally high or higher wage levels.

It is true that wages in unionized jobs tend to be higher than in nonunionized jobs for similar workers. Studies that compare the wages of unionized electricians to the wages of nonunionized electricians, for example, typically find that unionized electricians have wages about 10% to 15% higher than nonunionized electricians. But this doesn’t mean that unions could raise wages in all jobs because the primary method that unions use to raise wages is to reduce industry employment.3

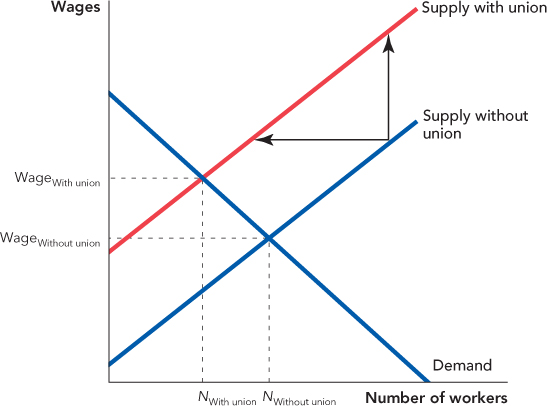

If you are wondering how unions raise wages and reduce employment, it is easy to see on a supply and demand graph. By restricting their membership and threatening to strike unless employers hire union labor, unions reduce the supply of labor to an industry. The reduction in labor supply shifts the supply curve for labor to the left and up, as shown in Figure 18.8. Notice that the reduction in the supply of labor increases wages but reduces employment from NWithout union to NWith union.

FIGURE 18.8

Unions can be beneficial in ensuring that employees are treated fairly and by improving labor/management relations, but the main reason that unions raise wages is through restricting the supply of labor. In this respect, a union is quite similar to a cartel, like those we discussed in Chapter 15. The OPEC oil cartel raises the price of oil by restricting the supply of oil and unions raise the wages of labor by restricting the supply of labor.

Unions also can lower wages, although this effect is more difficult to see. First, consider what happens to the workers who are not hired in the unionized industry—these workers must seek employment in other industries, which increases the supply of labor to those other industries and drives wages down. Second, unions sometimes bring strikes and work stoppages, which can slow down an entire economy. For instance, the British economy was highly unionized from 1970 to 1982; this coincided with Britain’s period of long economic decline relative to other nations.4 In 1970, dockworkers were on strike for so long that it shut down almost all of Britain’s main ports. Coal miners went on strike in 1972, which led to a shortage of electricity. A three-day workweek was implemented for a short time to save power. In 1974, the miners went on strike again and a shortened workweek was implemented again. Ten years later, the British experienced another strike that lasted for almost one year. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher limited the government-supplied privileges of the British unions during the 1980s. Since that time, Britain has grown rapidly and is now a wealthier country than the more unionized France or Germany.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 18.3

Suppose a new and cheap technology increases mine safety. What do you predict will happen to the wages of mine workers?

Suppose a new and cheap technology increases mine safety. What do you predict will happen to the wages of mine workers?

Question 18.4

Firms often help their employees improve their human capital by offering courses on things such as inventory management or underwriting their tuition for an MBA. Firms often attach strings to MBA education support, such as requiring that a supported-MBA stay at the firm for an additional five years. Firms usually do not attach any strings to an inventory management course. Why the difference?

Firms often help their employees improve their human capital by offering courses on things such as inventory management or underwriting their tuition for an MBA. Firms often attach strings to MBA education support, such as requiring that a supported-MBA stay at the firm for an additional five years. Firms usually do not attach any strings to an inventory management course. Why the difference?

When people think of unions, the longshoreman’s union or a union of electricians often comes to mind, but it’s important to remember that doctors, lawyers, dentists, accountants, and other professionals have their own type of union, called a professional association. The American Medical Association (AMA), for example, works to restrict the supply of physicians for the same reason that an electrician’s union works to reduce the supply of electricians. It’s very difficult to get into a medical school, for example. The AMA says that restricting the supply of physicians is necessary to maintain high standards. Maybe that is true, but restricting the supply of physicians also maintains high wages. The AMA lobbies for laws that make competing against physicians more difficult; for instance, they restrict the procedures that can be legally performed by nurse practitioners, midwives, chiropractors, and pharmacists and they make it more difficult for foreign-educated physicians to practice in the United States. As noted, the AMA says that restrictions are necessary to maintain quality and there is some truth to this claim, but as always, you should be somewhat skeptical when members of a group claim that their high wages are good for you!

The bottom line is this: unions can raise the wages of particular classes of workers, but unions are not the fundamental reason why wages are high in the wealthy countries.