How Bad Is Labor Market Discrimination, or Can Lakisha Catch a Break?

We all think we know what discrimination is. Discrimination is bad. Discrimination is what racists and bigots do. And, yes, that is partly right: Discrimination often is morally objectionable. It’s also true that there are different types of discrimination and not all discrimination is motivated by prejudice. Let’s take a closer look at two major types of discrimination, statistical discrimination and preference-based discrimination.

Statistical Discrimination

Let’s say you are walking down a dark alley, late at night, in the warehouse district of your city. Suddenly, you hear footsteps behind you. You turn around and you see an old lady walking her dachshund. Do you breathe a sigh of relief? Probably. Would you breathe the same sigh of relief if you saw an angry young man in a dark leather jacket, muttering to himself? What if he was holding a knife? What if he was walking with his two-year-old daughter in a baby stroller?

One way of reading this story is to claim that you are discriminating against young men, relative to old ladies, or relative to young men with baby girls at their side. Another way of describing this story is that you are using information rationally. An angry young man in a leather jacket is far more likely to mug you than is an old lady walking her dachshund. Maybe both descriptions capture some aspect of the reality, but suddenly discrimination isn’t so simple a concept anymore.

Statistical discrimination is using information about group averages to make conclusions about individuals.

Statistical discrimination is using information about group averages to make conclusions about individuals. Not every young man in a leather jacket walking the warehouse district late at night is a mugger and not every young man with a baby girl at his side is safe, but that’s the way to bet. Although statistical discrimination is a useful shorthand for making some decisions, it also causes people to make many errors. They refuse to deal with some people they really ought to. They may refuse to hire some people who deserve the job. We gave one example of this earlier—employers may not look carefully at workers without college degrees, even though some of these workers are just as intelligent and industrious as those with college degrees. It is called statistical discrimination because, in essence, the employer is treating the worker as an abstract statistic. Even though statistical discrimination is not motivated by malice, its long-run consequences can be harmful to the penalized groups.

Over time, markets tend to develop more subtle and more finely grained ways of judging people and judging job candidates. An employer can give prospective employees multiple interviews and psychological tests, Google previous histories or writings, look up people on Facebook, ask for more references, and so on, all to get an accurate picture of the person. Eventually, these practices break down the crudest methods of statistical discrimination but, of course, some statistical discrimination always remains.

Statistical discrimination tends to be most persistent when people meet in purely casual settings with no repeat interactions, such as in a dark alley late at night. It is profit-seeking employers, who make money from finding and keeping the best workers, who have the greatest incentive to overcome unfairness.

Preference-Based Discrimination

A second kind of discrimination—preference-based discrimination—is based on a plain, flat-out dislike of some group of people, such as a race, religion, or gender. We’re going to lay out three different kinds of preference-based discrimination: discrimination by employers, discrimination by customers, and discrimination by employees. The first of these is easiest for a market economy to overcome while the last is the most difficult to solve.

Discrimination by Employers When most people think of discrimination, they think of an employer with bigoted tastes. Some employers just don’t want to hire people of a particular race, ethnicity, religion, or gender. If this discrimination is widespread, the wages of people who are discriminated against will fall since the demand for their labor falls. But fortunately, this kind of discrimination, if taken alone, tends to break down for two reasons: Employer discrimination is expensive to the employer and it leaves the bigot open to being outcompeted.

Imagine, for example, that black workers are widely discriminated against and thus that their wages are lower than those of white workers. Say that a firm can hire white workers for $10 an hour or equally productive black workers for $8 an hour. Imagine that the firm needs 100 workers. If it hires black workers instead of white workers, the firm can increase its profits by $2 per hour per worker. Thus, by hiring black workers, the firm can increase its profits by $1,600 per day ($2 saving per hour for 100 workers for 8 hours a day), $8,000 per week (5 days a week), or $400,000 in a year (50 working weeks). Even a prejudiced employer will likely think twice about discriminating when it costs $400,000 a year just to indulge the prejudice.

Even if some employers are willing to pay the price of their prejudice, that gives other employers a chance to hire black workers and increase their profits. As profit-hungry employers compete for underpaid, discriminated-against workers, the wages of those workers will rise until wages are close to marginal product for all workers, as described.

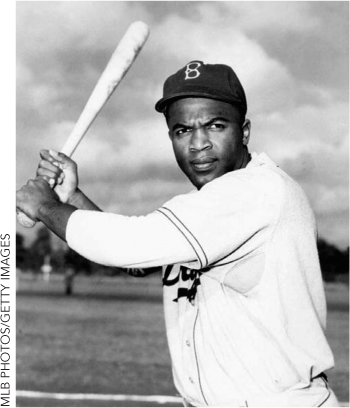

In 1947, Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey hired Jackie Robinson to be the first black player in modern major league baseball. Robinson already had extensive experience in what were then called the “Negro leagues,” and he proved to be an immediate star. Robinson won the Rookie of the Year award and then in his third season he won the MVP award. The first black player in the American League, Larry Doby, proved to be a star for the Cleveland Indians. The baseball teams that moved first to hire black players had a competitive advantage and eventually all teams had to follow, whether or not they were run by bigots.

Of course, that story is about baseball, but it applies to the broader world of business, as well. If employer-driven discrimination is unjustly depressing the wages of a group of people, you can make money by hiring them.

If the pursuit of profit raises wages so that all workers earn their marginal product, why do women earn less than men? It’s often said, for example, that women earn about 80 cents per dollar earned by men. The trouble with this widely reported statistic, however, is that it compares the wages of all women with those of all men—the statistic does not mean that a woman with the same qualifications earns less than a man for doing the same job.

One factor lowering wages for women as a group is that women tend to have less job experience than men of the same age because they sometimes leave the job force, typically to take care of children. In fact, if we compare the wages of single men and single women, single women earn just as much as single men. Married women without children also earn about as much as married men without children.

Men may also have specialized in higher-paying fields and they take more dangerous jobs. Remember those coal miners we discussed earlier with an average wage of $70,000? Most of them are men, perhaps because women prefer jobs with lower wages but less risk.

Over time, women have moved toward higher-paying sectors (more lawyers and economists, for instance) and there has been a long decline in the birth rate. Since women are having fewer children and they are having their children at later ages, that is helping women earn higher wages.

Nevertheless, some discrimination against women may yet remain, but it is probably more subtle than employer discrimination. We need to look at the roles of customers and employees to better understand other forms of discrimination.

Discrimination by Customers When the customers drive discrimination, owners are not always so keen to hire undervalued, victimized workers. If employing underpaid black workers upsets the customers, it’s not a surefire way for an employer to earn more money.

Let’s revisit the story of Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey. You might wonder why Branch Rickey hired Robinson in 1947 but not 1946. It’s not that one day Branch Rickey stopped being prejudiced against African Americans; he may not have been prejudiced in the first place. Rather, in 1947, Rickey sensed that his ticket-buying customers were ready for the idea of watching a black man play baseball in a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform. The lesson is that sometimes discrimination comes from the customers of a business, not always from the owners or managers.

Or let’s consider a lunch counter or hamburger joint in the Deep South in 1957, before the civil rights movement had much influence. Part of the problem was that state laws did not allow mixed-race establishments. But part of the problem came from customers, as well. At that time, many white customers didn’t like the idea of eating a hamburger while sitting next to a black man. These white customers demanded separate facilities, so usually there were separate lunch counters and separate restaurants for white and black people in many parts of the United States. The entrepreneur running the lunch counter may or may not have been racist, but in any case the preferences of his customers encouraged him to discriminate and to keep out black patrons.

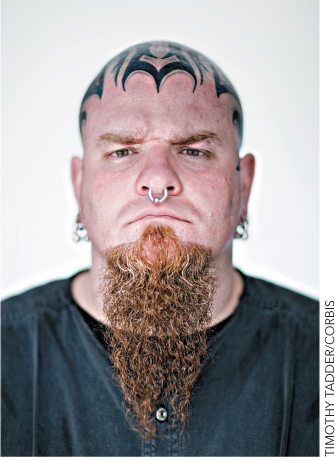

Don’t make the mistake of thinking customer-based discrimination has vanished from modern America. It’s usually done in a more subtle manner, but many country clubs, restaurants, and other businesses try to encourage “the right kind of customers.” They’re not always concerned about race per se, but often they seek customers who dress a certain way, have the right kind of jobs, come from the right part of town, and so on. The result is sometimes de facto segregation, even though the restaurant or country club owner is simply responding to the preferences of his consumers for a particular cultural style or “feel.”

By the way, the decline of employer-based discrimination, through market forces, also tends to weaken customer-based discrimination. Marketplace transactions bring different groups into regular contact with each other. Many white people who started listening to black music on the jukebox in the 1950s, or who saw Jackie Robinson play baseball, started asking themselves what was so wrong with integrated lunch counters. Discrimination is also weakened by economic growth more generally. For instance, declining costs of production make it possible for businesses to take more chances. If a small town has only two lunch counters, maybe neither will take a chance with integration. If the town grows and also the costs of starting a new business fall, suddenly there are seven lunch counters. Maybe one will experiment with integration. In the long run, no successful market economy has succeeded in maintaining widespread formal segregation.

Discrimination by Employees Customers and employers aren’t the only possible sources of discrimination. Sometimes workers don’t want to mix with people from different groups. In India, many workers don’t want to work alongside Dalits, workers from a low caste who are considered impure. In the United States, some firefighters—rightly or wrongly—don’t want women to have equal status in the firehouse. Similarly, some men in the armed forces don’t think that women should serve in combat and some men are looked on with suspicion if they want to work at a day care center.

The profit incentive doesn’t necessarily break down discrimination of this kind. An employer in India who hires Dalits, for example, may find that he has to pay other workers a higher wage to compensate them for the negative of working with Dalits. As a result, it’s cheaper to discriminate than to hire everyone equally. Similarly, if you hire a woman into an all-male firehouse that doesn’t want women, morale may fall and some men may leave for other jobs. As a result, employers are less likely to hire a person, even a productive person, from the victimized group.

Of course, an employer might hire only Dalits, or if women are not welcome in firehouses, an employer may set up an entirely new firehouse, one equipped with women and nonprejudicial men, but starting from scratch in this fashion isn’t always so easy to do.

Discrimination of this kind can be self-reinforcing and difficult to identify. If it’s unpleasant for women to work in firehouses, then many women who want to be firefighters won’t want to work in firehouses. Few women are hired but employers might say that’s because few women are applying. Maybe it won’t look like discrimination at all, but discrimination will still be a force at work.

Discrimination by Government So far we’ve been talking about discrimination in markets but it’s important to remember that governments discriminate, too. Government is sometimes part of the problem rather than part of the solution. We’ve already mentioned that prosegregation policies in the American South, before the civil rights movement, often came from governments. Governments required separate hospitals for black and white patients, separate public and private schools, separate churches, separate cemeteries, separate public restrooms, and separate restaurants, hotels, and train service. Before prosegregation laws were passed after the Civil War, many parts of the South were moving (albeit sometimes hesitantly) toward more integration.

The best known example of widespread government segregation was the apartheid system of South Africa, which was enforced from 1948 until the early 1990s. (“Apartheid” is a word in the Afrikaaner language that translates literally as “apartness.”) Under this arrangement, black people had to live in special areas and could not compete with white workers for many jobs. But this highly unjust situation was enforced by government laws, and enacted by white minority governments (black citizens also couldn’t vote). Once those laws were removed, black people moved into many jobs and received higher wages. Many forms of implicit segregation continue in South Africa, but some of the most egregious examples of discrimination have fallen away. Many employers are happy to hire the most productive workers they can find, regardless of the skin color or ethnic background of those workers.

Why Discrimination Isn’t Always Easy to Identify

Two economists had a neat idea. They sent around two sets of identical résumés. On one set of résumés, the names were quite traditional and did not identify the background of the person applying. An applicant named “John Smith,” for instance, could be either white or black. The second set of résumés had more unusual names on them—names like “Lakisha Washington” or “Jamal Jones.” As you may know, those are names closely associated with African Americans. Names can tell you a lot about who a person is. In recent years, more than 40% of the black girls born in California were given names that, in those same years, not one of the roughly 100,000 white newly born California girls was given.*

The result was striking: the resumes with the black names received many fewer interview requests. The job applicants with the “whiter” names received 50% more calls.

But that is not the end of the story. Steven Levitt (of Freakonomics fame) and Roland Fryer (a Harvard professor and an African American) set out to test how much African American names really mattered in the long run for earnings. It seems that having a “black name” does not appear to hurt a person’s chances in life, once the neighborhood that person comes from is controlled for. In other words, the number of interviews a person gets at first may not matter so much in the long run. Levitt and Fryer consider two possibilities. It may be that the so-called black names get fewer interviews, but they end up with jobs of equal quality. Alternatively, people with African American–sounding names may have fewer chances in white communities but greater chances in black communities; the two tendencies might balance each other out.

One point to note is that in the résumé experiment, by far the most common outcome of submitting a résumé, for both the white and black candidates and regardless of name, was not receiving any interview requests at all. The lesson is that just about everyone can expect a lot of rejection before they find the job that is right for them.

Did you know that good-looking people earn more, even if they have the same job credentials? That’s right, good-looking people earn about 5% more. Tall people earn more, too, again if they are compared with shorter people with the same paper credentials. Under one account, an extra inch in height translates into a 1.8% increase in wages.†

But these studies also show just how difficult it is to identify true discrimination. For instance, maybe tall people are paid more because they are more self-confident and not because anyone discriminates against shorter people. One study found that what best predicts wages, in this context, is the height a man had at the time of high school and not the height he ends up with as an adult. So if you were a tall person in high school, maybe that built up your self-confidence and makes you a better leader today, even if you stopped growing while your friends kept on getting taller.‡

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 18.5

From a profit-making perspective, why is employer discrimination just plain dumb?

From a profit-making perspective, why is employer discrimination just plain dumb?

Question 18.6

Of the three types of discrimination—employer, customer, employee—which has been affected most by market economies? Which has been affected least? Why?

Of the three types of discrimination—employer, customer, employee—which has been affected most by market economies? Which has been affected least? Why?

One question is why employers might prefer to hire tall people and to pay them more. One possibility is simply that the employer has an unreasonable preference against shorter people. Another possibility is that the employer is subconsciously tricked into thinking the taller leader is better, without ever realizing it. Yet another option is that the taller leader really is better (for the firm) because subordinates are more likely to pay that person respect. Again, we don’t know the right answer, and this illustrates just how difficult it is to estimate the scope of labor market discrimination.

In many cases, market forces have succeeded in making some discrimination go away, or at least markets have minimized some of the bad effects of discrimination. But few people doubt that discrimination remains a feature of our world today.