A Formula for Political Success: Diffuse Costs, Concentrate Benefits

SEARCH ENGINE

Extensive information on campaign contributions can be found at www.OpenSecrets.org.

The politics behind the sugar quota illustrate a formula for political success: Diffuse costs and concentrate benefits. The costs of the sugar quota are diffused over millions of consumers, so no consumer has much of an incentive to oppose the quota. But the benefits of the quota are concentrated on a handful of producers; they have strong incentives to support the quota. So, the sugar quota is a winning policy for politicians. The people who are harmed are rationally ignorant and have little incentive to oppose the policy, while the people who benefit are rationally informed and have strong incentives to support the policy. Thus, we can see one reason why the self-interest of politicians does not always align with the social interest.

The formula for political success works for many types of public policies, not just trade quotas and tariffs. Agricultural subsidies and price supports, for example, fit the diffused costs and concentrated benefits story. It’s interesting that the political power of farmers has increased as the share of farmers in the population has decreased. The reason? When farmers decline in population, the benefits of, for example, a price support become more concentrated (on farmers) and the costs become more diffused (on nonfarmers).

The benefits of many government projects such as roads, bridges, dams, and parks, for example, are concentrated on local residents and producers, while the costs of these projects can be diffused over all federal taxpayers. As a result, politicians have an incentive to lobby for these projects even when the benefits are smaller than the costs.

Consider the infamous “Bridge to Nowhere,” a proposed bridge in Alaska that would connect the town of Ketchikan (population 8,900) with its airport on Gravina Island (population 50) at a cost to federal taxpayers of $320 million. At present, a ferry service runs to the island but some people in the town complain that it costs too much ($6 per car). If the town’s residents had to pay the $320 million cost of the bridge themselves—that’s $35,754 each!—do you think they would want the bridge? Of course not, but the residents will be happy to have the bridge if most of the costs are paid by other taxpayers.

As far as the residents of Ketchikan are concerned, the costs of the bridge are external costs. Recall from Chapter 10 that when the costs of a good are paid for by other people—rather than the consumers or producers of the good—we get an inefficiently large quantity of the good. In Chapter 10, we gave the example of a firm that pollutes—since the firm doesn’t pay all the costs of its production, it produces too much. The same thing is true here, except the external cost is created by government. When government makes it possible to push the costs of a good onto other people—to externalize the cost—we get too much of the good. In this case, we get too many bridges to nowhere.

The formula for political success works for tax credits and deductions, as well as for spending. The federal tax code, including various regulations and rulings, is more than 60,000 pages long and it grows every year as politicians add special interest provisions. Tax breaks for various manufacturing industries, for example, have long been common, but in 2004, the term “manufacturing” was significantly expanded so that oil and gas drilling as well as mining and timber were included as manufacturing industries. The new tax breaks were worth some $76 billion to the firms involved. One last-minute provision even defined “coffee roasting” as a form of manufacturing. That provision was worth a lot of bucks to one famous corporation.

Every year Congress inserts many thousands of special spending projects, exemptions, regulations, and tax breaks into major bills. A multibillion-dollar lobbying industry works the system on behalf of their clients, and it is not unusual for those lobbies, in essence, to propose and even write up the details of the forthcoming legislation. In 1975, there were more than 3,000 lobbyists, by 2000 the number had expanded to over 16,000, and by the late 2000s there were more than 35,000 lobbyists—all to lobby just 535 politicians (435 representatives and 100 senators) and their staff. Many lobbyists are former politicians who find that lobbying their friends can be very profitable.

When benefits are concentrated and costs are diffuse, resources can be wasted on projects with low benefits and high costs. Consider a special interest group that represents 1% of society and a simple policy that benefits the special interest by $100 and costs society $100. Thus, the policy benefits the special interest by $100 and it costs the special interest just $1 (if you are wondering where that came from, $1 is 1% of the total cost to society). The special interest group will certainly lobby for a policy like this.

But now imagine that the policy benefits the special interest by $100 but costs society twice as much, $200. The policy is very bad for society, but it’s still good for the special interest, which gets a benefit of $100 at a cost (to the lobby) of only $2 ($2 is 1% of the total social costs of $200). Indeed, a special interest representing 1% of the population will benefit from any policy that transfers $100 in its favor, even if the costs to society are nearly 100 times as much!

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 20.2

President Ronald Reagan set up a commission to examine government and cut waste. It had some limited success. If special interest spending is such a problem, why don’t we set up another federal commission to examine government waste? Who would push for such a commission? Who would resist it? What will be its prospects for success?

President Ronald Reagan set up a commission to examine government and cut waste. It had some limited success. If special interest spending is such a problem, why don’t we set up another federal commission to examine government waste? Who would push for such a commission? Who would resist it? What will be its prospects for success?

Question 20.3

A local library expanded into a new building and wanted to establish a local history collection and room. The state senator found some state money and had that contributed to the library. Who benefits from this? Who ultimately pays for it?

A local library expanded into a new building and wanted to establish a local history collection and room. The state senator found some state money and had that contributed to the library. Who benefits from this? Who ultimately pays for it?

If each policy, taken on its own, wastes just a few million or billion dollars worth of resources, the country will be much poorer. A country with many inefficient policies will have less wealth and slower economic growth. No society can get rich by passing policies with benefits that are less than costs.

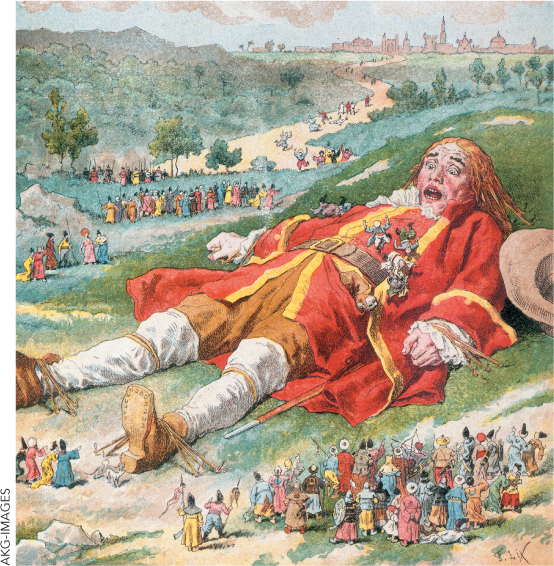

In extreme situations, an economy can falter or even collapse when fighting over the division of the pie becomes more profitable than making the pie grow larger. The fall of the Roman Empire, for instance, was caused in part by bad political institutions. As the Roman Empire grew, courting politicians in Rome became a more secure path to riches than starting a new business. Toward the end of the empire, the emperors taxed peasant farmers heavily. Rather than spending the money on roads or valuable infrastructure, the activities that had made Rome powerful and rich, tax revenues were used to pay off privileged insiders and to placate the public in the city of Rome with “bread and circuses.” When the empire finally collapsed in 476 CE, the tax collector was a hated figure and the government enjoyed little respect.3