21 Economics, Ethics, and Public Policy

CHAPTER OUTLINE

The Case for Exporting Pollution and Importing Kidneys

Exploitation

Meddlesome Preferences

Fair and Equal Treatment

Cultural Goods and Paternalism Poverty, Inequality, and the Distribution of Income

Who Counts? Immigration

Economic Ethics

Takeaway

Is it okay to export pollution from rich to poor countries? Larry Summers said not only that it was, but also that exporting pollution should be encouraged. Summers, if you don’t already recognize the name, is one of the best economists of his generation, and a former president of Harvard, secretary of the Treasury, and lead advisor to President Obama. In a memo to some of his colleagues when he was chief economist at the World Bank, Summers wrote:

Just between you and me, shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging more migration of the dirty industries to the LDCs [Less Developed Countries]? …

The measurements of the costs of health impairing pollution depend on the foregone earnings from increased morbidity and mortality. From this point of view a given amount of health impairing pollution should be done in the country with the lowest cost, which will be the country with the lowest wages. I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that.*

Unfortunately for Summers, his memo didn’t remain “just between you and me.” When it was leaked to the press, there was a firestorm of controversy, not just against Summers but against economics and the type of “impeccable” economic reasoning that Summers found convincing.

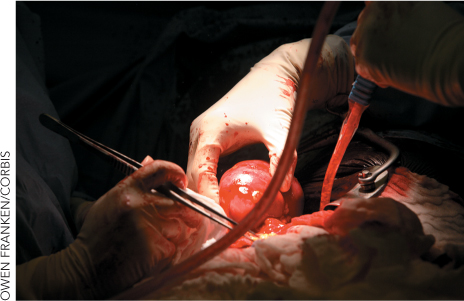

If you found Larry Summers’s memo disturbing, what about some of the ideas of Nobel prize–winning economist Gary Becker? Becker said that we should legalize the trade in human kidneys. In fact, in a survey, Robert Whaples found that 70% of the economists he surveyed (128 members of Economic Association) agreed or strongly agreed with this idea.1 Right now more than 100,000 Americans are waiting for kidney transplants. Many of them will die; others will undergo painful and exhausting dialysis for three days a week, four hours a day. The hospital waiting lists run for five years or more to get a kidney from a willing donor. In case you didn’t know, the law won’t allow kidneys to be bought and sold, so at a price of zero we have a severe kidney shortage (see Chapter 8 for a discussion of how price controls work).

Becker said that to alleviate the shortage, we should allow people to sell their kidneys (you only need one of the two you have). Many citizens of poorer countries would be willing to sell their kidneys for a few thousand dollars or less; in fact, some of these people are selling their kidneys on the black market right now.

Thus, we have two outstanding economists: one of whom said we should export pollution to poor countries, while the other said we should import kidneys from poor countries. No doubt, these two economists would probably also agree with each other!

Positive economics is describing, explaining, or predicting economic events.

Economists sometimes draw a distinction between positive economics and normative economics. Positive economics is about describing, explaining, or predicting economic events. For instance, if a quota restricts imports of sugar, the price of sugar will increase and people will buy less sugar. That’s true whether or not we think that sugar is good for people. Normative economics is about making recommendations on what economic policy should be. Is a sugar quota a good policy? That depends on what we think is good and who we think counts most when we measure benefits and costs.

Normative economics is recommendations or arguments about what economic policy should be.

Not all of this chapter is economics—much of it touches on ethics and morals—but it is still important material for understanding economics as a broader approach to the world. First, economics has limitations and you need to know what they are. It helps to know which ethical values are left out of economic theory. Second, sometimes you will hear bad or misleading arguments against economics, and you need to know those, too, and where they fall short.

We warn you, however, that in this chapter our primary goal is to raise questions rather than provide answers. And we try not to present our own normative claims. Instead, we consider the normative claims made by other people, especially critics of economics, and how they intersect with the positive economics that you have learned already.