The Demand Curve

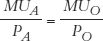

The optimal consumption rule also gives us an informal explanation for why a consumer’s demand curve slopes downward. Suppose that the consumer is currently maximizing utility, so the two-goods version of the optimal consumption rule says:

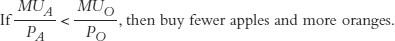

Now imagine that the price of apples PA increases. An increase in PA means that apples now provide less utility per dollar, so we have  . But recall our previous rule:

. But recall our previous rule:

We can see that an increase in the price of apples leads to the consumer buying fewer apples. The optimal consumption rule therefore gives us a foundation for demand curves based on individual choice.

The optimal consumption rule is an intuitive and useful way of thinking about how consumers choose to allocate their dollars, but we have derived the rule informally and in a form that makes it difficult to make specific predictions. It’s not obvious from the optimal consumption rule, for example, how changes in income affect choices. We also showed how an increase in PA means that a consumer should buy fewer apples and more oranges, but we didn’t say much about whether or when the dominant effect is fewer apples and when the dominant effect is more oranges. The theory, as we presented it, also puts this strange idea of “utils” front and center even though no one has ever seen a util. We can fix all of these problems and produce a richer, more complete theory by developing consumer choice theory a bit more formally. Fortunately, the optimal consumption rule will continue to hold true even in our richer model.